Key Takeaways

-

- Dental anesthesia is essential for pain-free treatment, ranging from local numbing to full unconsciousness.

-

- The most common type is **local anesthesia**, which targets specific nerves, leaving you awake but numb.

-

- Modern dental anesthesia is generally considered **very safe** for most patients when administered by trained professionals.

-

- Side effects are usually minor and temporary, like prolonged numbness or slight discomfort at the injection site.

-

- Duration varies greatly by type; local numbness lasts **1-4 hours** in soft tissue, while sedation/general anesthesia effects last for the procedure and wear off over several hours.

- Recovery requires simple precautions like avoiding chewing on the numb side until sensation returns.

Teeth anesthesia Explained: Understanding Dental Numbing

Stepping into a dental office, the promise of comfort often hinges on one crucial element: anesthesia. It’s the cornerstone of modern dentistry, the fundamental tool that allows practitioners to perform necessary procedures without causing undue pain or distress. At its heart, dental anesthesia is about managing sensation, specifically eliminating pain receptors in the mouth and surrounding tissues to create a numb, working environment for the dentist and a comfortable experience for the patient. When we talk about “teeth anesthesia,” “dental anesthetic,” or “mouth anesthesia,” we’re broadly referring to this process of inducing temporary numbness or a state of reduced sensation in the oral cavity. It’s not just about making things painless; it’s also about controlling reflexes like gagging and allowing complex, intricate work to be completed successfully and efficiently. Historically, dental pain management was a vastly different, often agonizing, affair. Early attempts involved everything from alcohol and opium to downright questionable methods. The advent of effective local anesthetics like cocaine (later replaced by safer alternatives) and the development of general anesthesia fundamentally transformed the practice, turning what was once a dreaded ordeal into a manageable, often anxiety-free, procedure. Understanding these terms – dentist anaesthetic, dentist anesthetic, mouth anesthesia, tooth anesthesia, dentist anesthesia, dental anesthesia – is key. They all point to the same core concept: using pharmacological agents to prevent the transmission of pain signals from the treatment site to the brain. For those who want to delve deeper into the academic side, resources like the articles in BJA Education or publications from institutions like UT Dentistry and major brands like Colgate® provide excellent foundational knowledge, highlighting the physiological mechanisms and clinical applications. These resources underscore that dental anesthesia isn’t just a simple jab; it’s a carefully considered medical procedure.

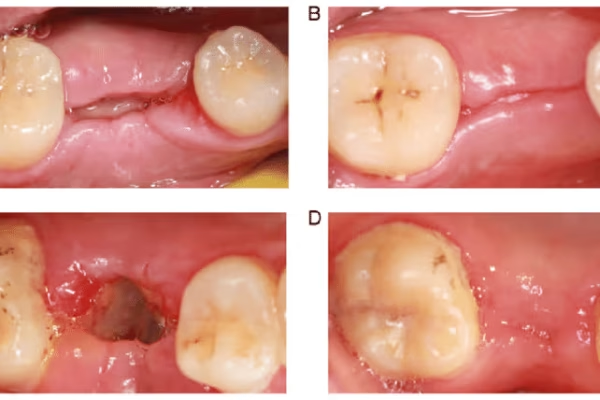

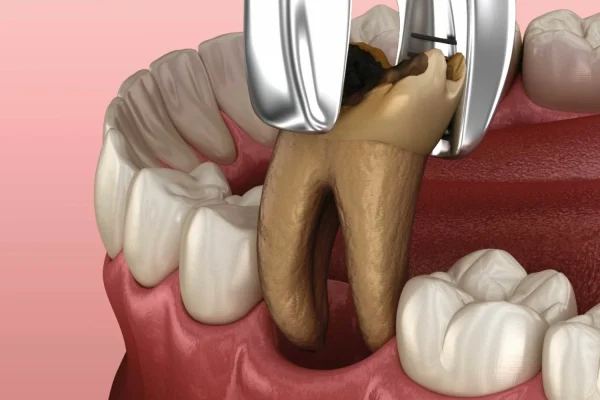

Which dental treatments require anesthesia?

You might wonder, “For what exactly will I need to get numb?” It’s a fair question, and the answer covers a surprisingly wide range of procedures. While a simple cleaning or routine check-up typically requires no more than a topical fluoride application, anything that involves working on or near the sensitive tissues of the tooth, gums, or bone usually necessitates anesthesia. Think about the common culprits of dental discomfort: cavities requiring fillings, where the dentist needs to drill into the tooth structure; extractions, which involve removing a tooth from its socket; root canal therapy, a procedure that goes deep into the tooth’s pulp chamber; or preparing teeth for crowns or bridges, which requires significant shaping of the tooth enamel. All these procedures involve manipulating nerve-rich tissues that would otherwise register significant pain signals. Anesthesia, primarily local anesthesia in these cases, blocks those signals, creating a pain-free zone. Without it, even relatively minor procedures like a deep filling would be excruciating. It’s absolutely crucial not just for your comfort, but also for the dentist’s ability to perform precise work without you flinching or reacting involuntarily. The depth and duration of the numbness needed will vary based on the complexity and invasiveness of the specific treatment. For example, a simple filling might require a different injection technique than a complex surgical extraction or a lengthy root canal. The dentist assesses the procedure and your individual needs to determine the appropriate type and amount of anesthetic. It’s the difference between a tolerable experience and one that could lead to severe anxiety and avoidance of necessary dental care.

What Types of Dental Anesthesia Are There?

When we talk about dental anesthesia, it’s not a one-size-fits-all scenario. Dentistry employs a spectrum of methods to manage pain and anxiety, ranging from simply numbing a specific area to rendering a patient completely unconscious. The choice of approach is a critical decision made by the dental professional, taking into account the nature and complexity of the procedure, your overall health, any underlying medical conditions, your level of anxiety or fear, and sometimes even your personal preference. Understanding these different types is key to feeling more comfortable and informed before your appointment. Generally speaking, we can categorize dental anesthesia and sedation into a few main groups, which range in intensity and effect. Many dental procedures only require the most basic form, while more complex or anxiety-inducing treatments might call for something stronger. Resources from oral surgery practices or dental anesthesia specialists often detail these options extensively, highlighting how they are tailored to individual patient needs. For example, you might encounter discussions around the three main types commonly used in oral surgery or the various sedation dentistry options available. It’s important to note that “anesthesia” often refers specifically to blocking pain signals, while “sedation” refers to reducing anxiety and making the patient relaxed or sleepy, though the two are often used in conjunction. The spectrum moves from mild relaxation to profound unconsciousness, each with its own set of applications and considerations.

What is the name of dental Anaesthesia?

It’s a common point of confusion, but “dental anesthesia” isn’t a single drug or agent with one specific name, like “Tylenol” for acetaminophen or “aspirin” for acetylsalicylic acid. Rather, it’s a broad category, an umbrella term that covers various pharmaceutical agents and techniques used to achieve numbness, pain relief, or a state of reduced consciousness for dental procedures. Think of it like asking “What is the name of surgery?”. Surgery isn’t one thing; it’s a collection of procedures performed using various tools and methods. Similarly, dental anesthesia encompasses a range of drugs and administration techniques. The specific agents used within this category belong to different pharmacological classes. The most common type you’ll encounter for routine procedures falls under the class of local anesthetics. These are drugs that, when injected into a specific area, temporarily block nerve conduction, preventing pain signals from reaching the brain from that localized site. While people often colloquially refer to “the shot” as “the novocaine,” Novocaine (procaine) is actually an older anesthetic that is less commonly used today due to higher rates of allergic reactions. Modern dentistry relies on newer, safer, and more effective local anesthetics. So, instead of one name, think of dental anesthesia as a collection of methods and medications used to achieve the desired level of pain control or sedation.

What anesthesia is used for teeth?

For the vast majority of routine dental work involving a single tooth or a small area, the go-to method is local anesthesia. This is the type most people are familiar with – the injection that makes your lip, tongue, or cheek feel temporarily puffy and numb, while effectively blocking any pain from the tooth or surrounding gum tissue being worked on. The goal here is to numb only the specific area necessary for the procedure, leaving you fully awake and aware, but comfortable. Dentists use several different drugs within the local anesthetic category, each with slightly different properties regarding onset time, duration, and potency. Common examples include Lidocaine (often marketed under names like Xylocaine), Articaine (brand names like Septocaine), Mepivacaine (brand names like Carbocaine), and Bupivacaine (brand names like Marcaine). Lidocaine has long been a standard due to its effectiveness and relatively low risk profile. Articaine is particularly popular in many parts of the world because it’s believed to diffuse better through bone, which can be advantageous for certain injections, especially in the lower jaw. These drugs work by reversibly binding to sodium channels in nerve cell membranes, preventing nerve impulses (including pain signals) from traveling along the nerve fibers. The specific drug and its concentration, as well as whether a vasoconstrictor is added, will be chosen by your dentist based on the procedure length and location, your medical history, and individual factors.

What are the types of dental anesthetics?

Delving a bit deeper into the specifics, the “types” of dental anesthetics can refer both to the class of anesthesia/sedation used (local, sedation, general) and the specific drugs employed within those classes. Focusing on the local anesthetics commonly injected to numb a tooth, you’ll frequently hear about drugs like Lidocaine, Mepivacaine, Prilocaine, Articaine, and Bupivacaine. These differ primarily in their chemical structure (categorized as either esters or amides, though most modern ones are amides), how quickly they start working (onset), how long they last (duration), and their potency. For instance, Lidocaine is a good all-around anesthetic with a moderate onset and duration. Bupivacaine has a slower onset but provides much longer-lasting numbness, which can be beneficial for pain control after a procedure, particularly surgical ones. A crucial element often added to these local anesthetics is a vasoconstrictor, most commonly epinephrine (also known as adrenaline). You’ll often see solutions like “Lidocaine with epinephrine 1:100,000” or “Articaine 4% with epinephrine (1:100 000)”. The vasoconstrictor does two main things: it constricts the blood vessels in the area of injection, which keeps the anesthetic concentrated at the site for longer (extending the numbness duration and making it more profound) and reduces bleeding during the procedure. However, the epinephrine can sometimes cause temporary side effects like a racing heart or jittery feeling, which is why plain solutions (without vasoconstrictor, e.g., “Bupivacaine 0.25–0.5% plain”) are used in certain situations, such as for patients with specific heart conditions, though they provide shorter-acting numbness.

What are the 4 types of anesthesia?

While dental anesthesia and sedation can be categorized in various ways, a common framework often breaks them down into three or four main levels or types based on the patient’s state of consciousness and responsiveness. If we use a four-tiered model, it typically looks something like this:

1. Local Anesthesia: As discussed, this involves numbing only the specific area being worked on. You remain fully awake and aware, able to communicate with the dental team, but you feel no pain in the numb area. This is the most common type for routine procedures like fillings, simple extractions, and basic crown preparations.

2. Minimal Sedation (Anxiolysis): Often achieved with oral medications (like a pill taken before the appointment) or inhaled nitrous oxide (“laughing gas”). You are relaxed, less anxious, but still awake and able to respond to commands. This primarily helps with anxiety and might offer some mild pain relief or dissociation.

3. Moderate Sedation (“Conscious Sedation” / “Twilight Sedation”): Often administered intravenously (IV sedation) or sometimes with higher doses of oral medication. You are significantly relaxed, may feel drowsy or even fall asleep, and might not remember much of the procedure afterwards (amnesia effect). You can still be easily roused and can respond to simple instructions, but you are not fully alert. IV Sedation (“Twilight Sedation”) falls squarely into this category.

4. Deep Sedation / General Anesthesia: With deep sedation, you are on the edge of consciousness, difficult to rouse, and may need help breathing. General anesthesia takes this further; you are completely unconscious, cannot be easily awakened, and typically require assistance with breathing (like a breathing tube). This level is reserved for complex oral surgery, very fearful patients, or those with special needs, and often involves an anesthesiologist or a dental anesthesiologist. Sedation dentistry encompasses minimal, moderate, and deep sedation, aiming to make patients comfortable and relaxed, while general anesthesia makes them completely unaware.

Which anesthesia is best?

Defining the “best” dental anesthesia isn’t about finding a single superior drug or method; it’s about determining the most appropriate approach for your specific situation. What’s best for one patient and one procedure might be entirely wrong for another. The “best” is a clinical judgment made by your dentist or oral surgeon, often in consultation with you, based on a careful assessment of several factors. These include: the planned dental procedure (its complexity, anticipated duration, and invasiveness); your overall health status (including any medical conditions, allergies, or medications you are taking, as these can affect how certain anesthetics or sedatives work or are metabolized); your personal level of anxiety or fear regarding dental treatment (a highly anxious patient might benefit more from sedation than local anesthesia alone); and sometimes, your own preference or past experiences. For a standard filling or single extraction, local anesthesia is usually the safest and most effective “best” option, providing targeted pain relief without affecting consciousness. For wisdom teeth removal or extensive surgery, IV moderate sedation or even general anesthesia might be considered “best” to manage pain, anxiety, and facilitate a smoother, less traumatic experience. The dentist weighs the benefits of pain control and anxiety reduction against the potential risks and side effects of each option. Never hesitate to discuss your concerns and preferences with your dentist; they are the best resource to help you understand why a particular type of anesthesia or sedation is recommended for you.

What anesthetic do dentists use to put you to sleep?

If the goal is to render you unconscious or in a state where you are deeply sedated and largely unaware of the procedure – essentially, “put you to sleep” – dentists don’t use standard local anesthetics like Lidocaine. Those drugs only numb a specific area. To achieve a sleep-like state, they utilize sedatives or general anesthetic agents that affect the central nervous system. There are different levels of “sleep” in dentistry. Moderate sedation, often called “Twilight Sedation” (usually via IV), makes you very relaxed, drowsy, and often leads to amnesia, so it feels like you were asleep, even though you might have been minimally responsive. Drugs like Midazolam (Versed) are commonly used for IV moderate sedation, sometimes combined with other medications. For actual unconsciousness – the kind where you are completely unresponsive and often need breathing assistance – this falls under General Anesthesia. General anesthesia in dentistry is typically reserved for complex surgical procedures, extremely anxious patients, young children, or individuals with special needs who cannot cooperate with treatment under local anesthesia or lighter sedation. This is usually administered by a qualified anesthesiologist or dental anesthesiologist via inhalation (breathing gases like Sevoflurane) or intravenous injection (drugs like Propofol). These powerful medications suppress brain activity to induce a state of controlled unconsciousness. Drugs used in combination with general anesthesia often include pain relievers (opioids), muscle relaxants, and anti-nausea medications, all carefully managed by the anesthesia provider.

What is the best anesthesia for tooth pain?

When the focus is specifically on eliminating pain during a dental procedure involving a tooth – whether it’s drilling, extracting, or working within the tooth’s structure – the undisputed champion is local anesthesia. This is the primary method used to block the transmission of pain signals from the specific tooth and surrounding tissues to your brain. Unlike systemic pain relievers you take by mouth (like ibuprofen or acetaminophen), which reduce inflammation or modulate pain perception generally, local anesthesia provides targeted, profound numbness exactly where it’s needed. It works by disrupting the nerve’s ability to send electrical impulses. The “best” specific local anesthetic drug for tooth pain management during a procedure depends on factors like the procedure’s expected length and the specific location of the tooth. Some drugs might have a faster onset for quicker numbing, while others might last longer, which is beneficial for lengthier procedures or for providing post-operative pain control as the numbness wears off. Vasoconstrictors like epinephrine are often added to local anesthetics used for tooth procedures because they help keep the anesthetic concentrated around the tooth’s nerve bundles for a stronger and longer-lasting effect, maximizing pain blockage. Sedation or general anesthesia might be used in conjunction with local anesthesia, particularly for anxious patients or complex procedures, but it’s the local anesthetic injection directly near the tooth’s nerves that provides the primary pain elimination during the actual work.

Which anesthesia is powerful?

The term “powerful” when referring to anesthesia can be interpreted in a couple of ways: the intensity of pain blocking or the level of effect on consciousness. If we’re talking about sheer pain-blocking capability in a localized area, local anesthetics are incredibly powerful. They completely prevent nerves from transmitting pain signals, achieving a state of complete analgesia (absence of pain sensation) in the target zone. Different local anesthetic drugs do have varying potencies – meaning how concentrated they need to be to achieve effective numbness – and durations of action. Bupivacaine, for example, is known for providing very long-lasting numbness, making it quite “powerful” in terms of duration and post-procedure pain control compared to shorter-acting agents. However, if “powerful” refers to the systemic effect on the body and the level of consciousness altered, then general anesthesia is the most powerful. It induces a state of complete unconsciousness and loss of sensation throughout the entire body, affecting brain function profoundly. Sedation falls somewhere in between, offering varying degrees of relaxation and detachment from the procedure, depending on the level (minimal, moderate, deep). So, for targeted pain elimination while awake, local anesthesia is powerfully effective. For systemic unconsciousness and complete unawareness, general anesthesia is the most “powerful” in its effect on the central nervous system. The “best” or most appropriate type isn’t necessarily the most “powerful” in either sense, but rather the one that best suits the specific needs of the procedure and the patient, balancing effectiveness with safety.

Is Dental Anesthesia Safe? Risks & Side Effects Explained

One of the most common questions patients have, understandably so, is about the safety of dental anesthesia. It involves injections, sometimes powerful drugs, and altering sensation – it’s natural to feel a bit apprehensive. The reassuring answer is that, yes, dental anesthesia, particularly the local anesthesia used for most routine procedures, is overwhelmingly considered safe for the vast majority of patients when administered by a trained professional. Dentistry has decades of experience with these medications and techniques, and their safety profiles are well-established. Millions of procedures are performed daily around the world using local anesthesia with minimal complications. Sedation and general anesthesia carry higher inherent risks because they affect the entire body and consciousness, but in a controlled environment with appropriate monitoring and qualified providers, they are also very safe for selected patients. Dental schools and professional organizations place a huge emphasis on rigorous training in anesthesia administration and emergency preparedness. Resources from major dental associations and universities consistently highlight the safety of these practices, emphasizing careful patient assessment beforehand to identify any potential risks. It’s crucial to provide your dentist with a complete and accurate medical history, including all medications and any known allergies, as this information is vital for selecting the safest anesthetic or sedation method for you.

Are there side effects from dental anesthesia?

Yes, like virtually any medication or medical procedure, dental anesthesia can have side effects. However, it’s important to frame this correctly: for local anesthesia, most side effects are minor, temporary, and localized to the area where the anesthetic was given. They are typically manageable and resolve on their own relatively quickly as the anesthetic wears off. Understanding what these common side effects are can help alleviate worry if you experience them. It’s also crucial to distinguish between common, expected effects (like numbness) and less common, potential side effects or complications. Resources specifically discussing the side effects of dental anesthesia provide comprehensive lists, but the key takeaway is that while possible, significant or dangerous side effects are rare in healthy individuals receiving local anesthesia. Sedation and general anesthesia naturally have a wider range of potential side effects because they affect the whole body, but these are anticipated and managed within the controlled clinical setting. Being aware of potential side effects is about preparedness, not necessarily prediction of a negative outcome.

What are the side effects of dental anesthesia?

Let’s break down the typical side effects you might encounter, focusing first on local anesthesia, as it’s the most common. The most obvious and intended “side effect” is, of course, numbness and tingling in the area of injection, including the tooth, gums, lip, tongue, and sometimes part of the cheek or face, depending on which nerve was targeted. This feeling of Novocain lip or mouth anesthesia is temporary but can persist for several hours. You might experience temporary swelling or tenderness at the exact injection site. If a vasoconstrictor like epinephrine was used, some people might feel a temporary increase in heart rate, palpitations, or a general jittery or anxious feeling immediately after the injection. This sensation can be alarming but is usually harmless and subsides quickly as the body processes the epinephrine. Less common local side effects can include temporary muscle twitching or drooping (rare). When considering sedation or general anesthesia, side effects are more systemic and can include drowsiness, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, headache, dry mouth, or feeling groggy or confused as the effects wear off. Some specific anesthetic drugs might also have unique side effect profiles. The terms oral anesthesia side effects, tooth anesthesia side effects, and anesthesia dentist side effects are all related – pointing to the potential reactions or consequences associated with these numbing and sedation methods in the mouth and dental context.

Is dental local anesthesia safe?

To reiterate and emphasize: yes, dental local anesthesia is widely considered one of the safest medical procedures performed routinely. Its safety record is excellent, particularly when administered by a qualified dental professional who has taken a thorough medical history and considered any potential contraindications or precautions. Local anesthetics are designed to work specifically at the site of injection by blocking nerve signals locally, without causing significant systemic effects in healthy individuals at therapeutic doses. The body quickly metabolizes and eliminates the drugs. Serious complications, such as allergic reactions or nerve injury, are exceedingly rare. The vast majority of adverse events associated with local anesthesia are either minor (like temporary pain at the injection site) or related to the vasoconstrictor (like feeling jittery). For most people, the benefits of being pain-free during dental treatment far outweigh the minimal risks associated with local anesthesia. Its widespread use over many decades across millions and millions of patients is a testament to its established safety profile. If you have specific health concerns, discussing them openly with your dentist allows them to tailor the anesthetic choice and dosage to maximize your safety.

What are the Risks of Dental Anesthesia?

While generally very safe, particularly local anesthesia, it’s important to be aware of the potential risks and complications, although they are uncommon to rare. For local anesthesia, risks include prolonged numbness (which can last longer than expected), temporary nerve damage (though rare and often temporary), hematoma (bruising caused by a blood vessel puncture), infection at the injection site, or breaking a needle (extremely rare with modern needles). The most discussed, though still rare, risk is an allergic reaction. True allergies to amide-type local anesthetics (the most common ones used today) are very infrequent, often manifesting as a rash, hives, or difficulty breathing in severe cases (anaphylaxis). More common reactions initially perceived as allergic are actually side effects of the vasoconstrictor (like rapid heartbeat) or anxiety-induced responses. Complications from sedation dentistry can include respiratory depression (breathing slowing down too much), changes in heart rate or blood pressure, or paradoxical reactions (where the sedative makes the patient agitated instead of calm). Risks of general anesthesia are more significant because it involves a deeper state of unconsciousness and requires constant monitoring of vital signs, including breathing and heart function. These risks can include nausea and vomiting, sore throat, muscle aches, confusion upon waking, and in rare cases, more serious cardiovascular or respiratory events. However, dental offices providing sedation or general anesthesia are equipped and staffed to manage these potential complications, and patient selection is crucial to minimize risk.

Allergic Reaction to Dental Anesthesia – How is Diagnosed?

True allergic reactions to modern dental local anesthetics (the amide type like Lidocaine, Articaine) are, thankfully, quite rare. Reactions that people sometimes experience, like a rapid heartbeat or feeling faint, are more often related to the epinephrine vasoconstrictor, anxiety, or a vasovagal response (fainting due to fear or pain). A true allergic reaction involves the immune system. Symptoms can range from mild, localized reactions like swelling, redness, or itching at the injection site hours or days later, to more immediate and severe systemic reactions like hives (urticaria), generalized rash, difficulty breathing (bronchospasm), swelling of the face or throat (angioedema), or even anaphylaxis, which is a life-threatening medical emergency. Symptoms of Reactions to Dental Anesthesia should always be reported to your dentist immediately. Diagnosing a true allergy to local anesthetics typically involves a process guided by an allergist or immunologist. This often starts with a detailed history of the suspected reaction. If the history strongly suggests an allergy, the allergist may perform skin testing or, in some cases, a carefully controlled challenge test where tiny, incremental doses of the suspected anesthetic (or alternatives) are administered under close medical supervision to observe for a reaction. This process, specifically How is Allergy to Local Anaesthetics Diagnosed, helps identify which specific anesthetic, if any, caused the reaction and helps determine safe alternatives for future dental work. Management (of allergic reaction to anesthesia) depends entirely on the severity; mild reactions might require antihistamines, while severe anaphylaxis requires immediate administration of epinephrine and emergency medical care.

Does dental anesthesia affect the brain?

The extent to which dental anesthesia affects the brain depends significantly on the type used. Local anesthesia, the most common type, is designed to primarily affect the nerves in the immediate area where it is injected. Its action is localized: it blocks the transmission of pain signals from the mouth to the brain by interfering with nerve function at the injection site. At standard therapeutic doses for routine dental work, local anesthetics do not typically cross the blood-brain barrier in sufficient concentrations to cause significant, noticeable cognitive effects or long-term changes in brain function in healthy individuals. You remain fully conscious, your thinking is clear, and your memory is intact. However, if local anesthetic is accidentally injected directly into a blood vessel, or if an excessive dose is administered, it can reach the bloodstream and potentially affect the central nervous system, leading to symptoms like dizziness, confusion, ringing in the ears, or even seizures in rare, severe cases. This is why careful injection technique and dosage calculation are crucial. On the other hand, sedation and general anesthesia are designed to affect the brain. Sedatives work by depressing the central nervous system to induce relaxation, drowsiness, or a state of reduced awareness. General anesthetics go further, causing a reversible loss of consciousness by profoundly affecting brain activity. These effects are temporary, and normal brain function resumes as the drugs are metabolized and cleared from the body. While some temporary cognitive effects, like grogginess or short-term memory impairment, can occur after sedation or general anesthesia, particularly in older adults, they are generally not associated with long-term brain damage in healthy individuals.

Why is my face still numb 2 days after dentist?

Experiencing numbness that lasts two full days after a dental appointment is uncommon and warrants contacting your dentist. While the expected duration of local anesthesia varies (usually 1-4 hours for soft tissues, sometimes longer for the tooth itself), numbness persisting beyond 24 hours is considered prolonged and should be evaluated. There are several potential reasons this might happen. One possibility is nerve trauma or irritation during the injection process. Although rare, the needle can sometimes directly injure or irritate a nerve bundle, leading to inflammation or temporary dysfunction that results in prolonged numbness or altered sensation (paresthesia or dysesthesia). This is sometimes referred to in literature discussing complications like Myotoxicity, though that term more specifically relates to muscle fiber damage. Another factor could be the type of anesthetic used. Longer-acting anesthetics like Bupivacaine are sometimes used for prolonged procedures or to provide extended post-operative pain control, but even these typically wear off within 8-12 hours, though residual altered sensation might linger slightly longer in some cases. Extremely rare complications might include nerve compression due to hematoma or swelling, or in exceptionally rare circumstances related to specific block techniques, Ocular complications (from anesthesia) affecting vision or eye movement due to unintended anesthetic spread. Your dentist can assess the situation, determine the likely cause, and discuss potential Differential Diagnosis & management (of anesthesia reactions) options if needed. Persistent numbness usually resolves over time, but seeking your dentist’s advice is important to monitor the situation and rule out anything requiring intervention. If side effects bother me, especially prolonged numbness, contacting the dental office is the first step.

Potential side effects

To summarize the range of potential side effects from dental anesthesia, it’s helpful to think of them on a spectrum from common and expected to rare and more serious.

Common/Expected: Numbness and tingling in the injection area (lip, tongue, cheek, gums, tooth); mild pain or soreness at the injection site; temporary swelling or bruising.

Less Common (especially with vasoconstrictor): Increased heart rate, palpitations, feeling jittery, anxiety, temporary pallor (whiteness) around the mouth.

Uncommon (more likely with sedation/general anesthesia but can occur with local): Dizziness, headache, nausea, vomiting, feeling groggy or confused, drowsiness, dry mouth.

Rare/Serious: Allergic reaction (rash, hives, swelling, difficulty breathing – anaphylaxis being the most severe); prolonged numbness or altered sensation lasting days or weeks (paresthesia); nerve injury; infection at the injection site; adverse drug interactions (if not disclosed); complications related to sedation/general anesthesia like respiratory or cardiovascular issues.

This isn’t an exhaustive list, but it covers the range. It’s vital to communicate your full medical history and any medications you take to your dentist to minimize the risk of adverse effects. They are trained to anticipate and manage these possibilities, ensuring your safety is the top priority.

How Long Does Dental Anesthesia Last?

The duration of numbness from dental anesthesia is one of the most common questions patients ask, and it’s a perfectly practical concern! You want to know when you can eat normally again or if you’ll be talking funny for hours. The answer isn’t a single number; it varies depending on several factors, primarily the type of anesthetic drug used, whether a vasoconstrictor (like epinephrine) was included, the amount administered, and the specific location of the injection (e.g., a small infiltration near a single tooth vs. a nerve block affecting a larger area). Generally speaking, when we talk about standard local anesthesia for routine procedures, the numbness felt in the soft tissues – your lip, tongue, and cheek – will typically last longer than the numbness in the tooth itself. This is because the soft tissues have a richer blood supply, which carries the anesthetic away more slowly when a vasoconstrictor is present. For most common local anesthetics with epinephrine, you can expect the soft tissue numbness to last anywhere from 1 to 4 hours. The numbness directly affecting the tooth being worked on is usually sufficient for the duration of the procedure (often shorter than the soft tissue numbness), typically lasting 1 to 2 hours, though this can vary significantly based on the drug and injection type. Resources like those from dental practices or clinics explaining the duration of dental anesthesia reinforce this variability.

How many hours is anesthesia for teeth?

Pinpointing the exact number of hours anesthesia lasts specifically for a tooth during a procedure requires a bit more nuance. The goal of the injection is to numb the nerves that supply sensation to that particular tooth. With common local anesthetics containing a vasoconstrictor, the profound numbness needed to perform work on the tooth itself usually lasts long enough to complete the procedure. For many fillings or straightforward extractions, this might mean the tooth is numb for 60 to 90 minutes of active work time, even if the surrounding soft tissue numbness persists for several hours afterward. For more complex procedures, a dentist might use a longer-acting anesthetic or reinject if necessary. The soft tissue numbness, which is often what you notice most acutely after leaving the office, typically lasts longer than the tooth-specific numbness because the drug remains in the less vascular soft tissues for a longer period. So, while your lip might feel numb for 3-4 hours, the tooth itself might only have been profoundly anesthetized for 1-2 hours during the core part of the treatment. The ‘hours’ of anesthesia really refer to the total time the drug is affecting the tissues, with the subjective feeling of numbness gradually fading.

How long does tooth anesthesia last?

Focusing specifically on the sensation (or lack thereof) in the treated tooth itself, the duration is primarily dictated by the specific anesthetic agent and the presence of a vasoconstrictor. A standard local anesthetic with epinephrine will numb the tooth’s nerve for a period usually sufficient to complete a typical procedure. As mentioned, this is often in the range of 1 to 2 hours of effective pain blocking for the tooth, although this can vary. Longer-acting agents like Bupivacaine, sometimes used for procedures where post-operative pain is anticipated to be significant, can provide profound tooth numbness for several hours (e.g., 4-8 hours), although their onset is slower. Without a vasoconstrictor, the anesthetic is carried away by the bloodstream much faster, resulting in a significantly shorter duration of action, often less than an hour for tooth numbness. The feeling of numbness in the surrounding gums, cheek, and lip will almost always outlast the numbness in the tooth itself. So, while you might regain some sensation in the tooth after an hour or two, that floppy lip feeling could easily stick around for 3-5 hours.

How Long Does Each Type of Anesthesia Last?

Understanding the duration based on the different types of anesthesia provides a clearer picture:

-

- Local Anesthesia: This is the most variable depending on the specific drug and vasoconstrictor.

-

- Standard Amides (Lidocaine, Articaine, Mepivacaine with epinephrine): Soft tissue numbness typically lasts 1-4 hours. Tooth numbness duration for the procedure is usually adequate (e.g., 1-2 hours of profound effect), but overall drug presence affects nerves for the longer duration.

-

- Longer-acting Amides (Bupivacaine with epinephrine or plain): Soft tissue numbness can last 4-8 hours or even longer. Tooth numbness can also be significantly prolonged, providing extended post-operative pain relief.

- Without Vasoconstrictor (e.g., Mepivacaine or Bupivacaine plain): Duration is much shorter, often 30-60 minutes for soft tissues and tooth, as the anesthetic is quickly dispersed.

-

- Local Anesthesia: This is the most variable depending on the specific drug and vasoconstrictor.

-

- Sedation: The duration here refers to how long the sedative effect lasts, not numbness.

-

- Inhaled Sedation (Nitrous Oxide): Effect is only felt while breathing the gas and wears off within minutes after the mask is removed. No residual effects.

-

- Oral Sedation: Effects begin within 30-60 minutes and can last for 2-6 hours or longer, depending on the specific drug and dosage. You’ll feel groggy and need a ride home.

- IV Sedation (“Twilight Sedation”): Effects are immediate and can be adjusted during the procedure. You will feel drowsy and relaxed for the duration, typically 1-4 hours depending on the procedure length. Full recovery from the grogginess might take several hours, necessitating a ride home and rest.

-

- Sedation: The duration here refers to how long the sedative effect lasts, not numbness.

- General Anesthesia: Duration refers to the period of unconsciousness. This is carefully controlled by the anesthesiologist to last precisely as long as needed for the procedure. Recovery involves waking up in a supervised area and can take several hours to feel fully alert, with residual grogginess possible for the rest of the day.

Knowing these general timelines helps set expectations for post-appointment activities and recovery.

Is Dental Anesthesia Painful?

It’s perhaps the most common fear associated with dental anesthesia: the injection itself. The thought of a needle near or in your mouth can understandably cause apprehension. So, let’s tackle this directly: Is dental anesthesia painful? The honest answer is that you will likely feel something, but modern techniques aim to minimize discomfort significantly. The initial sensation is usually described as a brief pinch or sting, followed quickly by the feeling of the anesthetic solution entering the tissue, which can feel like pressure or a dull ache. This discomfort is usually momentary. The goal of the injection is to prevent pain during the procedure, and while the delivery mechanism (the needle) isn’t inherently comfortable, dentists employ several strategies to make it as painless as possible.

Is anesthesia in teeth painful?

Focusing on the sensation of the injection around the teeth: the brief, sharp sensation is usually from the needle penetrating the gum tissue, not necessarily from the anesthetic reaching the tooth itself immediately. Once the anesthetic begins to spread and numb the area, any subsequent sensation is greatly diminished. Dentists often apply a topical anesthetic gel or liquid to the injection site before inserting the needle. This numbs the surface tissue, so the initial needle stick is barely felt or not felt at all. The dentist then inserts the needle gently and often injects the anesthetic solution very slowly. Injecting too quickly can cause more pressure and discomfort as the tissue stretches. By using topical anesthetics and a slow injection technique, dentists can significantly reduce the sensation of the “shot” itself, making it much more tolerable than many people fear. While “pain-free” is the ultimate goal of the anesthesia’s effect, the process of receiving it might involve a brief, localized discomfort.

What is the most painful injection at the dentist?

Identifying the single “most painful” injection is subjective, as pain perception varies greatly from person to person. However, based on common patient reports and anatomical considerations, certain injection sites or techniques can be perceived as more uncomfortable than others. In the upper jaw (Maxillary anaesthesia), infiltrations (where the anesthetic is injected directly into the gum tissue near the tooth root) are generally considered less painful than nerve blocks, as the tissue is less dense. In the lower jaw (Mandibular anaesthesia), achieving numbness often requires a Mandibular block, which targets a major nerve bundle further back in the jaw. This injection site is deeper and involves more tissue penetration, which some patients find more uncomfortable than simple infiltrations. Palatal injections (into the roof of the mouth) can also be quite sensitive due to the dense tissue and limited space. However, again, experienced dentists use techniques to minimize pain, such as topical anesthetic, warming the anesthetic solution, injecting slowly, and sometimes applying pressure near the injection site to distract the nerves (related to principles like the Gate Control Theory in Painless Anaesthesia). While some spots might be inherently more sensitive, the dentist’s skill and techniques play a huge role in managing any potential discomfort during the injection process.

How is Dental Anesthesia Administered?

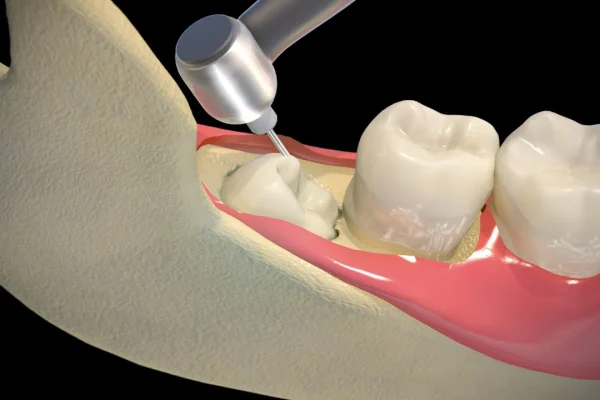

The process of receiving dental anesthesia is a carefully planned and executed procedure designed to ensure effectiveness and minimize discomfort. It’s not just a random jab! Dentists follow specific protocols based on the location of the tooth, the nerves that supply it, and the type of anesthesia being used. For local anesthesia, which is the most common, the process usually involves a few steps after the area is prepared. Resources detailing Local Anesthesia Techniques in Dentistry and Oral Surgery provide in-depth information on these procedures.

Where do dentists inject anesthesia?

The location of the injection depends entirely on which tooth or area needs to be numbed, as different nerves supply different parts of the mouth. For upper teeth (Maxillary anaesthesia), dentists often use infiltration, injecting the anesthetic directly into the gum tissue near the tip of the root of the tooth. Because the bone in the upper jaw is relatively porous, the anesthetic solution can diffuse through the bone to reach the nerves entering the tooth. For lower teeth (Mandibular anaesthesia), especially back teeth, the bone is much denser, so infiltration is often less effective. Instead, dentists commonly perform a Mandibular nerve block, injecting the anesthetic near the nerve as it enters the lower jawbone, numbing half of the lower jaw, including the teeth, lip, and tongue on that side. There are also other, less common sites and techniques, such as injections directly into the gum papilla between teeth (Intra-papillary), into the ligament surrounding the tooth (Intraligamentary), into the bone (Intraosseous), or even directly into the tooth’s pulp (Intrapulpal) if the tooth is already partially numb but still sensitive inside (e.g., during a root canal). Jet injection uses pressure instead of a needle for surface numbing but is not typically used for profound tooth anesthesia. The goal is always to deposit the anesthetic solution as close as safely possible to the nerve(s) supplying the area that needs to be numb.

Anaesthetic procedure

A typical anaesthetic procedure for local numbing begins with the dentist preparing the area. They might dry the tissue to improve visibility. Then, they almost always apply a topical anesthetic gel or liquid to the surface of the gum where the injection will occur. This topical agent numbs the very surface layers, making the initial needle prick less noticeable. After allowing the topical to work for a minute or two, the dentist will use a dental syringe – a specialized syringe designed for dental injections, often with a visible cartridge of anesthetic solution – to administer the injection. They will carefully insert the fine needle into the tissue at the predetermined site and slowly inject the anesthetic solution. Injecting slowly is crucial for patient comfort and to prevent the anesthetic from dispersing too quickly. The dentist may aspirate (gently pull back on the plunger) before injecting to ensure the needle is not inside a blood vessel. Once the anesthetic is deposited, it begins to diffuse through the tissues to reach the target nerves. Numbness usually starts to set in within a few minutes, though the onset time varies depending on the specific anesthetic and technique used. The dentist will typically test the area to ensure it’s profoundly numb before starting the dental procedure.

Most common local anesthetic procedure

The most common local anesthetic procedures performed involve infiltration in the upper jaw and Mandibular nerve blocks in the lower jaw. Infiltration is straightforward: topical anesthetic, gentle needle insertion into the gum tissue near the tooth root, slow injection. It’s generally less intimidating for patients due to its relatively superficial nature. The Mandibular block, while sometimes perceived as more involved due to its target location further back in the mouth, is the workhorse for achieving profound numbness in the lower teeth. This block numbs the inferior alveolar nerve, which supplies all the lower teeth on that side, as well as the lip and chin. It requires precise anatomical knowledge to locate the injection site near the nerve’s entry point into the bone. For front lower teeth, infiltration can sometimes be effective, but the denser bone still often makes a nerve block (like a mental block or incisive block) necessary for profound numbness. These standard techniques form the foundation of pain control in routine restorative and surgical dentistry.

Dental syringe

The dental syringe is the familiar tool used to inject local anesthetic. It’s different from typical medical syringes. The most common type is the aspirating syringe. It consists of a barrel where the anesthetic cartridge (a small glass cylinder containing the anesthetic solution) is placed, a plunger with a harpoon, and a needle attachment. The “aspirating” mechanism is crucial: the harpoon on the plunger engages with a rubber stopper in the anesthetic cartridge, allowing the dentist to pull back slightly on the plunger after inserting the needle into the tissue. If blood enters the cartridge upon aspiration, it means the needle is inside a blood vessel, and the dentist will reposition the needle before injecting the anesthetic. This aspiration step is a critical safety measure to prevent injecting local anesthetic directly into the bloodstream, which could lead to systemic side effects or toxicity. The needles used are very fine and come in different gauges and lengths, chosen based on the injection site and technique. While some newer “safety syringes” or even computer-controlled anesthetic delivery systems (like ‘The Wand’) exist, the traditional aspirating dental syringe remains a widely used and effective instrument in dental practices worldwide for administering local anesthesia precisely and safely.

How is the IV Sedation Administered?

IV Sedation, often referred to as “Twilight Sedation” because it puts you in a deeply relaxed state where you’re semi-conscious or feel like you’ve drifted off, is administered differently than local anesthesia. Instead of injecting into the mouth, the sedative medication is delivered directly into your bloodstream through a small needle placed in a vein, usually in your arm or hand. This method allows the medication to reach your brain and body very quickly, providing immediate relaxation and anxiety relief. Before the IV is placed, the site on your arm or hand is cleaned, and a local anesthetic cream or spray might be used to numb the skin for the initial needle stick. Once the IV line is established, it’s taped securely, and medication is administered through it. The dental team or a qualified sedation provider (like an anesthesiologist or a dentist trained in IV sedation) can control the level of sedation throughout the procedure by adjusting the flow of medication. They constantly monitor your vital signs, including heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen levels, and breathing, using specialized equipment. What happens during sedation dentistry when IV sedation is used is that you’ll become very relaxed, drowsy, and potentially fall asleep. You might still be able to respond to verbal cues, but you’ll likely have little to no memory of the procedure afterward due to the amnesic effects of some sedatives. It’s a very effective way to manage significant anxiety and undergo longer or more complex procedures comfortably.

Intraosseous, Intraligamentary, Intra-papillary, Intrapulpal, Jet injection

These terms refer to less common or specialized techniques for administering dental anesthesia, often used in specific clinical situations or as alternatives to standard blocks and infiltrations.

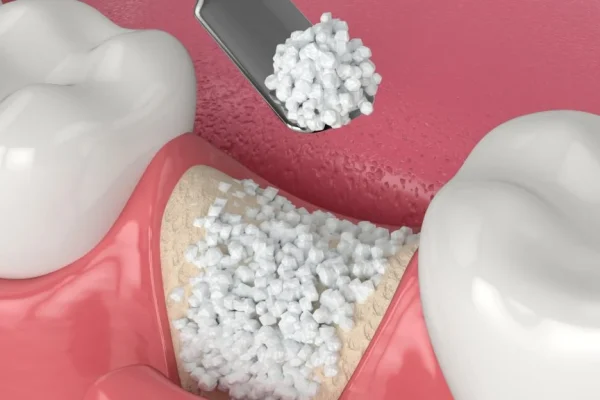

* Intraosseous anesthesia: Involves injecting the anesthetic directly into the cancellous bone surrounding the tooth’s root. This provides very rapid and profound numbness specifically to the tooth, bypassing the need for diffusion through dense bone. It’s often used when standard nerve blocks are ineffective or contraindicated.

* Intraligamentary anesthesia: (also called PDL injection, for periodontal ligament) Involves injecting the anesthetic directly into the ligament that holds the tooth in its socket. Using a special high-pressure syringe or a standard syringe with a fine needle, small amounts of anesthetic are injected around the tooth. This technique provides rapid, localized numbness to a single tooth and avoids numbing the lip or tongue, making it useful for specific situations, though it can sometimes cause temporary discomfort or tooth soreness.

* Intra-papillary anesthesia: Involves injecting a small amount of anesthetic into the gum tissue papilla (the triangular gum tissue) between two teeth. This is primarily used for numbing the gum tissue itself before procedures like placing rubber dams or performing minor gum surgery in a localized area.

* Intrapulpal anesthesia: This is a last-resort technique used when the tooth’s pulp (the nerve and blood vessel tissue inside the tooth) is exposed and remains sensitive despite other forms of local anesthesia, particularly during root canal treatment on a tooth with irreversible pulpitis (“hot tooth”). A small amount of anesthetic is injected directly into the pulp chamber. While initially uncomfortable, it provides immediate and profound numbness to the pulp, allowing the procedure to continue painlessly.

* Jet injection: Uses compressed air or gas to force liquid anesthetic through the skin or mucosa under high pressure, creating a fine stream that penetrates the tissue without a needle. While useful for achieving surface numbness (like before a standard injection), it does not provide deep enough penetration for profound tooth anesthesia and is not commonly used as the primary method for numbing teeth for restorative work or extractions.

These techniques demonstrate the versatility of dental anesthesia delivery to meet diverse clinical needs. Pressure anesthesia often refers to techniques like intraligamentary injections where pressure helps force the anesthetic into the desired area, or applying pressure during a standard injection to aid diffusion and reduce pain perception.

What Happens After Dental Anesthesia? Recovery & Precautions

Okay, the drilling’s done, the tooth is fixed, and you’re ready to leave. But the anesthesia isn’t! The most noticeable thing after dental anesthesia, especially local anesthesia, is the lingering numbness. This can affect your ability to speak clearly, eat, or drink normally until it wears off. Recovery from dental anesthesia isn’t typically complex, especially with just local numbing, but there are important precautions to take to ensure you don’t accidentally injure yourself while sensation is impaired. If you’ve had sedation, the recovery is a bit different and requires more vigilance. Resources like those discussing special precautions when taking dental anesthetics or what happens after sedation dentistry provide helpful guidelines.

What not to do after tooth anesthesia?

The most critical “what not to do” is anything that could injure your mouth while it’s numb. Because you can’t feel temperature or pressure normally in the numb area, you can easily bite your lip, cheek, or tongue without realizing it. So, do not bite or chew on the numb side until sensation has completely returned. This is especially important for children, who might find the numb feeling novel and be tempted to explore it with their teeth. Similarly, avoid hot foods or drinks in the numb area. You won’t be able to gauge the temperature accurately and could scald yourself. It’s best to wait until you can feel normally again before eating or drinking anything hot. Also, avoid strenuous activity immediately after a local anesthetic injection, particularly one with epinephrine. While not strictly forbidden, increased blood flow can potentially speed up the dispersal of the anesthetic slightly, and if you feel jittery from the epinephrine, intense physical activity might exacerbate that sensation. Generally, take it easy until the numbness subsides.

Can I eat after dental anesthesia?

You can eat after dental anesthesia, but it’s strongly advised to wait until the numbness has worn off completely. The primary risk of eating while your mouth is numb is accidental injury. Imagine taking a bite and severely biting your lip or cheek because you can’t feel it – it happens, and it can cause painful sores or swelling that last for days. Can you eat while my mouth is numb? Technically yes, you can put food in your mouth and chew, but it’s risky. If you absolutely must eat before the numbness is gone (e.g., you’re diabetic and need to maintain blood sugar), stick to very soft foods that require minimal chewing and consume them very carefully, being hyper-aware of where your lip, cheek, and tongue are. Lukewarm or cold, soft foods like yogurt, smoothies, or soup (cooled down!) are safer choices if you can manage them without chewing on the numb side. But the safest approach is patience – just wait an hour or two until you can feel normally again.

Can I drink water after dentist anesthesia?

Drinking clear, cold liquids like water is generally safer than eating while numb, but caution is still necessary, especially if your lip or tongue is significantly affected. You can drink water after dentist anesthesia, but be mindful. If your lip is numb, water can dribble out of your mouth. If your tongue is numb, swallowing might feel slightly awkward, and there’s a slight theoretical risk of aspiration (accidentally inhaling liquid into your lungs) if your gag reflex is significantly impaired, although this is less common with typical local anesthesia dosages compared to deeper sedation. Cold water might feel strange against the numb tissue. It’s usually safe to sip water cautiously once you’ve checked that you have a decent swallow reflex and can control the liquid in your mouth, but again, if the numbness is profound in your tongue or throat, waiting a bit longer or using a straw to direct the liquid past the most numb areas might be advisable. Avoid hot drinks for the same reason as hot food – risk of burns.

Can you sleep with dental anesthesia?

Local anesthesia alone does not make you sleepy. It only numbs the local area. So, if you’ve only had a local injection, you will remain fully awake and alert and cannot simply “sleep” the numbness off, though resting quietly is certainly fine. If you’ve received sedation, however, the goal is often to make you feel drowsy or even fall asleep. With moderate IV sedation or deep sedation, you might drift into a sleep-like state during the procedure and continue to feel very sleepy afterward. In this case, post-sedation recovery involves resting or sleeping under supervision (initially in the dental office) and then at home. With general anesthesia, you are intentionally put into a state of unconsciousness, which is essentially a medically induced sleep. So, whether you can or should sleep with dental anesthesia depends entirely on the type administered. Local numbing? Stay awake. Sedation or general anesthesia? Sleep is part of the process and recovery.

How to remove anesthesia from mouth?

This is a frequent question, but unfortunately, there’s no quick trick or button you can push to instantly “remove” dental anesthesia from your mouth and make the numbness disappear. The anesthetic effect wears off naturally as your body’s bloodstream carries the drug away from the injection site and your liver and kidneys metabolize and eliminate it. The duration depends on the factors we discussed earlier (type of drug, vasoconstrictor, amount). While increased blood flow might theoretically speed up the process slightly, vigorous exercise immediately after a procedure isn’t typically recommended, especially if you’ve had sedation or felt jittery from epinephrine. Trying to stimulate the area (like rubbing it) won’t make the numbness go away faster and might even cause irritation. Patience is key. Just wait it out. Eat soft, cool foods carefully if needed, and be mindful of the numb area until sensation returns. The numbness is a temporary state, and your body is already working to return things to normal.

What is the recovery time?

The “recovery time” after dental anesthesia refers to how long it takes for the effects of the anesthesia or sedation to wear off and for you to feel back to normal.

* Local Anesthesia: Recovery mainly involves waiting for the numbness to subside. Soft tissue numbness typically lasts 1-4 hours, but can be longer with certain drugs or techniques. Once sensation returns, you’re generally considered recovered in terms of the anesthetic effect.

* Inhaled Sedation (Nitrous Oxide): Recovery is almost immediate. The effects wear off within minutes of stopping the gas, and you can usually drive yourself home.

* Oral Sedation: Recovery takes longer. You’ll feel groggy and potentially have impaired coordination for several hours (e.g., 2-6+ hours). You will need someone to drive you home and should plan to rest for the remainder of the day.

* IV Sedation: Recovery involves an initial period of supervised recovery in the dental office until you are more alert. You will still feel drowsy and should not drive, operate machinery, or make important decisions for the rest of the day (typically 12-24 hours, depending on the drugs used).

* General Anesthesia: Recovery is the longest. You’ll wake up gradually in a recovery area, feeling groggy, potentially nauseous, and disoriented. You’ll need constant supervision and assistance to get home and should plan for a full day or more of rest and impaired function.

Always follow your dentist’s specific post-operative instructions, which will include guidance tailored to the type of anesthesia you received and the procedure performed. Precautions to Take When Undergoing Dental Anesthesia often involve fasting instructions beforehand (especially for sedation/general anesthesia) and arranging for a responsible adult to accompany you and drive you home.

Is it possible to drink alcohol before and after dental anesthesia?

Generally, it is strongly advised to avoid drinking alcohol both before and after dental anesthesia, especially if you are receiving any form of sedation or general anesthesia. Alcohol is a central nervous system depressant. Combining alcohol with sedatives or anesthetics can amplify their effects, leading to potentially dangerous respiratory depression (slowing or stopping of breathing) and profound over-sedation. Even with local anesthesia alone, alcohol can interact with some medications or simply impair your judgment and coordination, which is not ideal before or after a procedure. Furthermore, alcohol can affect blood clotting and potentially interfere with the metabolism of anesthetic drugs. After receiving any type of sedation or general anesthesia, alcohol should be avoided for at least 24 hours (or longer, as advised by your dentist) because your system is still recovering, and the lingering effects of the drugs can be dangerously enhanced by alcohol. It’s always best to be completely honest with your dentist about your alcohol consumption, as this is part of taking a comprehensive medical history to ensure your safety. When in doubt, err on the side of caution and abstain.

Special Considerations for Dental Anesthesia

While dental anesthesia is generally safe for the average healthy adult, certain medical conditions, life stages, or specific needs require extra careful consideration and planning when it comes to selecting and administering anesthetic or sedative agents. Dentists and anesthesia providers are trained to assess these factors and modify their approach accordingly. This ensures that patients with unique circumstances receive safe and effective pain and anxiety control tailored to their individual health profile. Dental considerations in anaesthesia are a crucial part of a dental professional’s training, often involving coordination with the patient’s physician or specialists. Resources like articles from the PMC database highlight the importance of a thorough medical history and patient assessment.

Dental anesthesia in pregnancy

Pregnancy is a time when many women are understandably cautious about taking medications or undergoing medical procedures. When it comes to dental anesthesia, specifically local anesthesia (like Lidocaine with epinephrine), it is generally considered safe for use during pregnancy when administered appropriately. Dental infections and untreated dental problems can pose greater risks to both the mother and the developing fetus than necessary dental treatment performed with local anesthesia. The goal is to use the lowest effective dose and minimize potential exposure, but delaying essential treatment can have negative consequences. Local anesthetics are categorized by the FDA regarding their safety in pregnancy (many commonly used ones are Category B, suggesting no evidence of risk in animal studies, though human studies are limited). The vasoconstrictor (epinephrine) is also generally considered safe in typical dental doses, though its use is carefully considered in pregnant patients with certain cardiovascular conditions like severe preeclampsia. Can I have sedation dentistry if I’m pregnant? This is more complex. Nitrous oxide is generally avoided during pregnancy, especially in the first trimester, due to potential risks, though brief exposure in the later stages is sometimes deemed acceptable with caution. Oral and IV sedation are generally approached with much more caution during pregnancy and are typically only considered if absolutely necessary and after consultation with the patient’s obstetrician, weighing the risks and benefits carefully. Local anesthesia and the pregnant patient is a topic where open communication between the patient, dentist, and OB/GYN is paramount to ensure safe and effective care.

Contraindications

Contraindications are specific situations or conditions that make a particular treatment or medication inadvisable or potentially harmful. For dental anesthesia and sedation, contraindications can vary depending on the specific agent and method being considered. Absolute contraindications (meaning the treatment should definitely not be used) are rare for local anesthesia but can include a documented, true allergy to the specific class of local anesthetic (e.g., amide type). Relative contraindications (meaning the treatment should be used with caution, modified, or an alternative should be chosen) are more common. These can include certain cardiovascular conditions (like recent heart attack, unstable angina, uncontrolled high blood pressure or arrhythmias) which might require limiting or avoiding the use of vasoconstrictors like epinephrine; certain neurological disorders; liver or kidney disease which might affect how the drug is metabolized; specific drug interactions with medications the patient is taking; or certain respiratory conditions (especially for sedation/general anesthesia). Pregnancy, as discussed, can be a relative contraindication for certain sedation methods. A thorough review of your medical history and current medications by your dentist is essential to identify any potential contraindications and ensure the chosen anesthetic approach is safe for you.

Special needs (in anesthesia context)

Patients with “special needs” in the context of dental anesthesia often include those with significant medical complexities, physical or intellectual disabilities, extreme dental anxiety (odontophobia), very young uncooperative children, or individuals with conditions that affect their ability to cooperate with dental treatment while awake (e.g., severe gag reflex, movement disorders). For these patients, local anesthesia alone may not be sufficient to allow for necessary dental work. They may require modifications to standard local anesthesia techniques, or more commonly, the use of sedation (minimal, moderate, or deep) or general anesthesia to safely and effectively provide care. For example, a patient with a severe intellectual disability might require general anesthesia for even routine procedures to ensure their safety and cooperation. A patient with profound dental phobia might benefit greatly from IV sedation to reduce anxiety and allow treatment to be completed comfortably. Patients with certain heart conditions, respiratory issues, or seizure disorders require careful assessment and potentially consultation with their physician before sedation or general anesthesia is administered. The goal is to provide the necessary dental care in the safest and most humane way possible, using the appropriate level of anesthesia or sedation to manage pain, anxiety, and movement as needed.

Benefits of Dental Anesthesia

Let’s not forget the immense upsides! While we’ve discussed potential side effects and risks, it’s vital to highlight the significant benefits that dental anesthesia brings to both patients and practitioners. It’s a cornerstone of modern, humane dental care and vastly improves the experience for everyone involved. Asking “Is dental anesthesia good?” is like asking if seatbelts are good – the answer is a resounding yes, because of the crucial advantages they offer.

-

- Enables Painless Procedures: This is the most obvious and important benefit. Dental anesthesia eliminates or significantly reduces pain during procedures that would otherwise be intensely uncomfortable or unbearable. This allows patients to receive necessary care without suffering.

-

- Allows Dentists to Work Effectively and Efficiently: When a patient is comfortable and not reacting to pain, the dentist can focus on performing the procedure with precision and without interruption. This leads to higher quality work and often shorter appointment times for complex treatments.

-

- Reduces Patient Anxiety and Fear: For many people, the fear of pain is the biggest barrier to seeking dental care. Knowing that anesthesia will prevent pain can significantly reduce anxiety, making patients more willing to undergo necessary treatments and maintain their oral health. This benefit is magnified by sedation dentistry, which specifically targets anxiety.

-

- Makes Complex or Lengthy Procedures Possible: Procedures like root canals, surgical extractions, or extensive restorative work that can take significant time and involve sensitive tissues would be impossible or severely traumatic without effective anesthesia and potentially sedation. Anesthesia allows these vital treatments to be completed in an outpatient setting.

- Improved Patient Experience: Overall, anesthesia transforms the dental visit from a potentially dreaded event into a much more manageable and comfortable experience, fostering trust and encouraging patients to return for regular check-ups and treatments, which is key to long-term oral health.

The benefits far outweigh the risks for the vast majority of patients undergoing routine dental procedures with local anesthesia.

What is the cost of local anesthesia?

When budgeting for dental work, patients often wonder about the cost of the different components, including anesthesia. For standard local anesthesia (the numbing injection you get for a filling or extraction), the cost is almost always included in the overall fee for the dental procedure itself. Dentists don’t typically break out the cost of a few milliliters of Lidocaine as a separate line item on your bill. It’s considered an integral part of providing the service of, say, a filling or a crown preparation, and its cost is factored into the total price you pay for that specific treatment. So, if you’re just getting a simple filling with local anesthetic, you won’t see a separate charge for “anesthesia” on your statement. However, this changes dramatically when you move beyond basic local numbing into sedation or general anesthesia. The cost of sedation dentistry or general anesthesia is a significant additional fee on top of the cost of the dental procedure. This is because it requires specialized drugs, equipment, monitoring, and often involves a separate provider (a sedation dentist or an anesthesiologist) whose time and expertise are billed separately. The cost of sedation or general anesthesia can vary widely depending on the type used (oral sedation is usually less expensive than IV sedation, which is less expensive than general anesthesia), the duration of the procedure, the location of the practice, and the specific provider. If your procedure is planned to involve sedation or general anesthesia, the dental office will discuss these separate costs with you beforehand, as they can add hundreds or even thousands of dollars to the total bill.

Frequently Asked Questions About teeth anesthesia

We’ve covered a lot of ground, but let’s consolidate some of the key takeaways by revisiting common questions. Think of these as quick refreshers based on what we’ve explored in detail. Having these answers readily available can help ease last-minute jitters before your appointment. Remember, open communication with your dental team is always your best resource for specific questions related to your individual health and planned treatment. Don’t hesitate to ask them to clarify anything you’re unsure about regarding your anesthesia plan.

What anesthesia is used for teeth?

For routine procedures involving a tooth, local anesthesia is the primary type used. This involves injecting a numbing medication, commonly Lidocaine or Articaine (often with epinephrine), near the nerve supplying the tooth. The goal is to make the specific tooth and surrounding gum tissue completely numb and pain-free while you remain fully awake and aware. Other forms of anesthesia like sedation or general anesthesia are used in addition to local anesthesia for managing anxiety or for complex surgical procedures, but local anesthesia is what directly targets the pain from the tooth itself during the procedure.

Are there side effects from dental anesthesia?

Yes, side effects are possible, although for local anesthesia, they are typically mild, temporary, and localized. Common side effects include lingering numbness in the lip, tongue, or cheek; temporary soreness or swelling at the injection site; and sometimes, a temporary jittery feeling or rapid heartbeat if a vasoconstrictor like epinephrine is used. Less common risks include prolonged numbness or, rarely, allergic reactions or nerve injury. Side effects from sedation or general anesthesia are more systemic (grogginess, nausea) but are managed in a controlled setting. Most side effects resolve within hours or days.

How long does tooth anesthesia last?

The duration of numbness varies. The feeling of profound numbness in the tooth itself, sufficient for a procedure, typically lasts for 1 to 2 hours with common local anesthetics containing a vasoconstrictor. The noticeable feeling of numbness in the surrounding soft tissues (lip, tongue, cheek) generally lasts longer, often 1 to 4 hours, and sometimes even longer with longer-acting agents. Sedation effects last from minutes (nitrous oxide) to several hours (oral or IV sedation), while general anesthesia lasts for the duration of the controlled unconsciousness.

Is dental anesthesia painful?

The process of receiving dental anesthesia, specifically the injection, may involve a brief pinch or sting, followed by a feeling of pressure or dull ache as the anesthetic is administered. However, dentists use techniques like topical numbing gels and slow injection to significantly minimize this discomfort. The goal of the anesthesia itself is to eliminate pain during the procedure, which it does very effectively. While the moment of injection might have a fleeting sensation, it is generally well-tolerated and much less painful than undergoing treatment without it.

Is dental anesthesia safe?

Yes, dental anesthesia, particularly local anesthesia, is considered very safe for the vast majority of patients when administered by a trained dental professional who has reviewed your medical history. Millions of procedures are performed safely every day using these methods. While risks and side effects exist, they are uncommon to rare. Sedation and general anesthesia also have high safety records when performed in appropriate settings with qualified providers for carefully selected patients. Your dentist will assess your health to choose the safest option for you.