Key Takeaways

-

- Molars are the large back teeth primarily used for grinding food.

-

- Adults typically have 12 molars (including wisdom teeth), anchoring the bite.

-

- Eruption timing varies: baby molars 1-3 yrs, permanent molars 6-13 yrs, wisdom teeth 17-25 yrs.

-

- Common molar issues include cavities, gum disease, cracks, impaction, and Molar Hypomin.

-

- Pain is a common symptom, often requiring professional dental diagnosis and treatment.

-

- Lost permanent molars should ideally be replaced using options like implants, bridges, or dentures to prevent long-term problems.

- Diligent brushing, flossing, and regular dental check-ups are crucial for preventing molar pain and maintaining health.

Molar Teeth: Anatomy, Types, and Essential Functions Explained

Let’s start with the basics, shall we? Molar teeth are the large, flat teeth positioned at the back of your mouth. Their name comes from the Latin word ‘mola’, meaning ‘mill’, which perfectly describes their primary function: grinding food into a pulp that’s easy to swallow and digest. Without these sturdy structures, your ability to properly process nuts, grains, or even a good steak would be significantly hampered. They are the workhorses of your dentition, designed for power and endurance. In a typical adult mouth, you usually have twelve molars in total – six on the top jaw (maxilla) and six on the bottom jaw (mandible), though this number can vary depending on whether wisdom teeth make an appearance or are removed. These are distinct from your front teeth (incisors and canines) which are sharper and used for cutting and tearing, and the premolars (also known as bicuspids) which sit between the canines and molars and serve a transitional role in chewing, possessing characteristics of both.

When we talk about the different types of molars, we’re usually referring to their position from the front of the mouth working backwards. You have your first molars, which are the closest to the premolars and are often the largest and strongest. Then come the second molars, sitting just behind the first. And finally, the infamous third molars, more commonly known as wisdom teeth, which are the furthest back. Functionally, the first and second molars are absolutely vital for efficient chewing. They have broad, flat surfaces with multiple raised points called cusps – typically four or five on the top molars and four on the bottom – designed to crush and grind food effectively. Underneath the gum line, their anatomy is equally robust. Molars have multiple roots anchoring them firmly into the jawbone. Upper molars usually have three roots, while lower molars typically have two. This multi-rooted structure provides stability for the significant forces exerted during chewing. Specific locations like the Mandibular molar sites, referring to the lower jaw’s molar positions, are particularly important areas dentists assess due to common issues like impaction (especially with wisdom teeth) and the complex root structure that can impact procedures like root canals. Understanding the intricate relationship between these deep roots and the surrounding bone and nerves is crucial for dental health and any potential treatments. The official term for a molar tooth, Dens molaris, simply reinforces its identity as a grinding tooth. While wisdom teeth share the “molar” classification and function, their often problematic eruption and positioning set them apart, frequently requiring specific management. Essentially, every tooth behind your canines has a grinding role to play, but the molars, particularly the first and second, are the undisputed champions of mastication. They are the foundation of your bite and the primary reason you can enjoy a diverse diet.

When do molars come in? Understanding Eruption Timing

Ah, the arrival of molars – a milestone often met with a mixture of anticipation and dread, especially for parents navigating the choppy waters of baby teething! Understanding the timeline for molar eruption, both for primary (baby) teeth and permanent teeth, can help alleviate some of the mystery and prepare you for potential discomfort. For primary molars, the eruption typically begins between 13 and 19 months for the first molars, followed by the second molars coming in around 25 to 33 months. These timelines can vary slightly from child to child, but that’s the general window when you might start seeing these broad chewing surfaces pushing through the gums at the back of the mouth. Fast forward a few years, and the process repeats with permanent teeth. The first permanent molars are often the very first permanent teeth to erupt, usually appearing around age 6 or 7, behind the last primary molar. This is why they are often called the “six-year molars.” The second permanent molars typically arrive between ages 11 and 13, sitting behind the first permanent molars. These are sometimes referred to as the “12-year molars,” a name that often causes confusion with wisdom teeth.

To directly answer the question: What age do molars come in? For the first set (primary), think roughly 1-3 years old. For the crucial permanent set (excluding wisdom teeth), the first arrive around 6-7, and the second around 11-13. This timeline is key for parents, as highlighted by resources like the Orajel™ Kids guide on getting permanent teeth. Now, for the third molars – the wisdom teeth – their arrival is notoriously later and much more variable. What age do wisdom teeth come in? Typically, they erupt between the ages of 17 and 25. This later eruption is precisely why they’re called “wisdom teeth” – they arrive when you’re supposedly older and wiser. It’s important to clarify that the 12-year molars are NOT the same as wisdom teeth. The 12-year molars are your second permanent molars, while wisdom teeth are the third. This distinction is crucial for tracking dental development. Variability is a hallmark of wisdom teeth; some people never develop them, while others may see them erupt partially, fully, or become impacted (stuck). And yes, while less common, Can I get wisdom teeth at 40? While the prime eruption window is 17-25, it’s not impossible for wisdom teeth to shift or partially erupt later in life, though it’s less likely to be a standard, smooth eruption. Understanding these timelines is step one in managing the arrival and potential issues associated with these vital back teeth.

What are the symptoms of teething in molars? Navigating Discomfort

Teething is a challenging phase for both babies and parents, and the arrival of those big, flat molars can often be particularly trying. While any teething can cause discomfort, the symptoms when baby molars are erupting can sometimes feel more intense simply due to the larger surface area pushing through the gums and the significant pressure involved. Common signs include increased fussiness or irritability, difficulty sleeping (because the pressure often feels worse when lying down), excessive drooling, swollen or tender gums around the back of the mouth, and a strong urge to chew on objects. Parents might notice their little one rubbing their cheeks or ears on the side where a molar is coming in – the pain can radiate slightly. How these symptoms might differ from front teeth teething isn’t always dramatic, but the general discomfort level might seem higher, and locating the source of pain in the back of the mouth can be harder for the parent. The urge to chew might also be more pronounced as the child tries to counter the pressure.

A common concern parents have is: Can molars make baby sick? This is a bit of a debated topic in the medical community, but generally, teething itself doesn’t directly cause systemic illness like a high fever, diarrhea, or significant vomiting. However, the stress and discomfort of teething can sometimes lower a baby’s resistance slightly, making them more susceptible to mild infections. Also, excessive drooling can sometimes lead to a mild cough or gagging, and increased fussiness and poor sleep can simply make a baby seem “off” or unwell. While a slight increase in temperature is sometimes noted, high fevers should always be investigated as potentially being due to an underlying illness, not just teething. Diarrhea is also not a direct symptom of teething, although swallowed excess saliva can sometimes loosen stools slightly. If your baby seems truly sick with high fever or persistent diarrhea, it’s crucial to consult a doctor to rule out other causes. For adults or older children, How do I know if my molars are growing? (specifically wisdom teeth or even late-erupting second molars) the signs are similar: pain or pressure at the back of the jaw, tenderness or swelling in the gums in that area, sometimes a bad taste in the mouth if the gum flap over the erupting tooth gets infected, or difficulty opening the mouth fully. For many, there’s simply a noticeable ache or pressure sensation at the very back. How bad is molar teething? It varies hugely from child to child and tooth to tooth. For some, it’s mild annoyance; for others, it can be quite painful and disruptive for several days or even weeks as the tooth slowly pushes through. While it’s tough, it’s a normal part of development, and managing the discomfort is key.

Why are my molar teeth hurting? Causes and Relief

Molar pain? Been there, felt that! It’s an incredibly common complaint, and for good reason. These teeth are constantly under pressure, involved in heavy-duty work, and due to their location at the back, they can sometimes be trickier to clean effectively. This combination makes them susceptible to a range of issues that can cause significant discomfort. So, Why are my molar teeth hurting? The culprits are varied, but some of the most frequent include cavities. Molars have pits and fissures on their chewing surfaces where food particles and bacteria love to hide, making them prime real estate for decay. If a cavity gets deep enough to reach the nerve, it can cause intense pain. Gum disease (periodontitis) can also affect the tissues and bone supporting your molars, leading to pain, looseness, and sensitivity. Cracks or fractures in a molar, often caused by biting down on something hard or grinding teeth (bruxism), can expose the sensitive inner layers of the tooth to temperature changes and pressure, resulting in sharp pain. Impaction, particularly with wisdom teeth, is another major source of pain; a tooth trying to erupt but lacking space can cause pressure, swelling, and infection. Sinus infections can also sometimes manifest as pain in the upper molars because the roots are close to the sinus cavity.

Are molar teeth more painful? Compared to other teeth, molar pain can feel more severe because the molars are larger, have multiple roots (meaning more nerve tissue), and the issues affecting them (like deep cavities or impaction) often involve significant inflammation or pressure. The typical Molar pain symptoms range from a dull, persistent ache that’s hard to ignore to sharp, shooting pain when biting down or exposed to hot/cold. You might also experience swelling in the gums or jaw around the affected tooth, a bad taste in your mouth (if there’s infection), or pain that seems to radiate to your ear or temple. For temporary relief, several home remedies can help: rinsing with warm salt water can reduce swelling and clean the area; cold compresses on the outside of the cheek can numb the pain; and over-the-counter pain relievers like ibuprofen or acetaminophen can help manage discomfort and inflammation. However, these are just temporary fixes. What relieves molar pain? Ultimately, treating the underlying cause is the only way to achieve lasting relief. This is why it’s crucial to seek professional dental help when molar pain occurs. A dentist can diagnose the specific issue and recommend the appropriate treatment, whether it’s a filling, root canal, gum therapy, extraction, or addressing an impaction. Ignoring molar pain rarely makes it go away and can lead to more serious problems down the line. How to Prevent Molar Pain largely comes down to consistent, good oral hygiene: diligent brushing (especially reaching those back teeth!), daily flossing, and regular dental check-ups and cleanings. Prevention is always less painful and less expensive than dealing with the aftermath of neglect.

Wisdom teeth (third molars): Common Issues and Removal

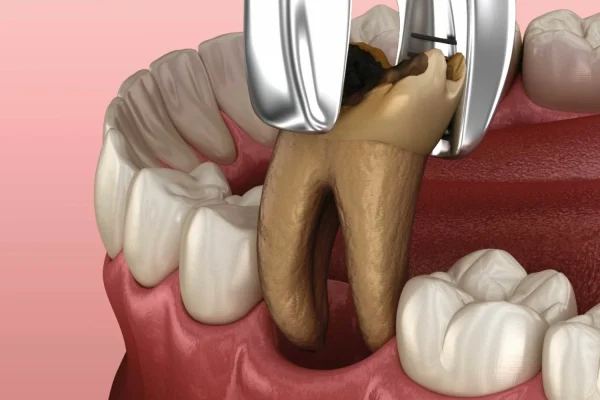

Ah, wisdom teeth. The dental equivalent of that awkward relative who shows up unannounced and causes trouble. These are your third molars, the final set to erupt, typically making their grand appearance between the late teens and early twenties, though sometimes later. While some lucky individuals have their wisdom teeth erupt smoothly and fit perfectly into their jawline, providing additional chewing power, this is unfortunately not the norm for many. Often, there simply isn’t enough space at the back of the jaw to accommodate them properly. This lack of space is the primary reason Why remove wisdom teeth? The most common issue is impaction, where the tooth gets stuck beneath the gum line or jawbone, either partially or completely unable to erupt fully. Impacted wisdom teeth can push against the adjacent second molar, causing damage or increasing the risk of decay in both teeth. They can also create a flap of gum tissue (operculum) over the partially erupted tooth, trapping food and bacteria and leading to painful inflammation and infection (pericoronitis). Even if they erupt fully, wisdom teeth are so far back that they are difficult to clean effectively, making them prone to cavities and gum disease. Crowding of existing teeth is another potential issue, though the extent to which wisdom teeth cause significant orthodontic relapse is debated.

Given these potential problems, dental professionals frequently recommend removal, especially if they are impacted or causing recurrent issues. What age do you get your molars out? If we’re talking wisdom teeth, this usually happens between 17 and 25, coinciding with their typical eruption period. However, they can be removed earlier if problems are anticipated or later if issues develop. The wisdom teeth removal procedure varies depending on whether the tooth is fully erupted, partially impacted, or fully impacted within the bone. Fully impacted teeth require a more involved surgical extraction. Patient concerns often revolve around pain: How painful is wisdom teeth removal? It’s a surgical procedure, so some pain, swelling, and discomfort are expected during recovery. However, pain management with prescribed medication and following post-operative instructions usually keeps it manageable. Mandibular third molar surgery recovery (lower wisdom teeth) can sometimes be a bit more involved than upper teeth recovery due to denser bone and proximity to nerves, but healing typically takes a few days to a couple of weeks for full recovery. Swelling peaks 2-3 days after surgery. What are the side effects of removing wisdom teeth? Common side effects include swelling, bruising, pain, stiffness in the jaw, and slight bleeding. Less common, but potential, risks include dry socket (where the blood clot dislodges), infection, temporary or rarely permanent numbness of the lip, tongue, or chin (due to nerve proximity), and damage to adjacent teeth or fillings. Comparing pain levels, Which is more painful, root canal or wisdom tooth extraction? This is highly subjective and depends on the complexity of both procedures and individual pain tolerance. A root canal addresses infection within a tooth, while extraction is surgical removal of a tooth. A straightforward root canal might be less painful than a complex, bony impacted wisdom tooth extraction, but a severely infected tooth needing a root canal can cause excruciating pain beforehand. Post-procedure pain also varies. Modern Contemporary Management of Third Molars focuses on evidence-based assessment, weighing the risks of removal against the risks of keeping the tooth. Not all wisdom teeth need to come out, but monitoring them is always advised.

Should I remove a molar tooth? General Extraction Considerations

Beyond the common narrative of wisdom teeth removal, sometimes other molar teeth – your first or second molars – may need to be extracted. This is a decision dentists don’t take lightly, as these teeth are so critical for function. However, certain situations make extraction necessary to preserve overall oral health and prevent future problems. So, Should I remove a molar tooth? The answer depends entirely on the tooth’s condition and the surrounding oral environment. Scenarios where extraction might be necessary include severe, irreparable decay that has destroyed too much tooth structure to be saved by a filling or crown, extensive trauma that has fractured the tooth or root beyond repair, advanced gum disease that has caused significant bone loss around the tooth, leading to looseness, or occasionally for orthodontic reasons to create space in a crowded arch. Your dentist will carefully evaluate the tooth using X-rays and clinical examination to determine if it can be saved or if extraction is the best course of action.

Can a dentist remove a molar? Yes, absolutely. General dentists routinely perform many molar extractions, especially for teeth that are fully erupted and have relatively straightforward root anatomy. However, if a molar is impacted (other than a typical wisdom tooth, which is a third molar), has complex or curved roots, or if there are underlying medical conditions that require extra precautions, your dentist might refer you to an oral surgeon, who is a specialist in surgical extractions and managing complex cases. The general process of molar extraction involves numbing the area thoroughly with local anesthetic. Once the area is numb, the dentist or surgeon will carefully loosen the tooth from the jawbone using specialized instruments and then gently remove it. For surgical extractions (often needed for impacted teeth or those that break during removal), a small incision in the gum or removal of some bone may be necessary. Providing insight into whether the procedure Does removing a molar hurt? The goal is to make it painless during the procedure itself thanks to the anesthetic. You will feel pressure and movement, but sharp pain should not be present. Post-operatively, pain is expected as the anesthetic wears off, but this is managed with prescribed or over-the-counter pain medication. Following post-extraction instructions for care is crucial for proper healing and minimizing discomfort. Discussing specific cases like Can I remove my first molar? The first molars are among the most important teeth you have because they are often the first permanent teeth to erupt and play a central role in developing the bite. Removing a first molar is usually considered a last resort due to its critical function. Dentists will go to great lengths to save a first molar if possible, often recommending procedures like root canals or crowns before considering extraction. If a first molar must be removed, discussing replacement options is particularly important due to its significance. Finally, briefly touching upon the potential long-term effects: The extraction of first, second or third permanent molar teeth and its effect on the dentofacial complex has been studied, showing that removing teeth can lead to changes in bite alignment, shifting of adjacent teeth, and bone loss over time, highlighting why replacement is often recommended after extraction.

Is it OK to live without a molar? Understanding Tooth Loss

Losing a permanent tooth, especially a molar, is a significant event for your oral health and overall well-being. These teeth are not like baby teeth designed to fall out and be replaced. When a permanent molar is lost, the space left behind doesn’t simply fill itself in. The consequences of losing a permanent molar can extend far beyond just a gap in your smile. Adjacent teeth, lacking the support and contact point of the lost molar, can begin to drift or tilt into the empty space. The opposing tooth in the other jaw, without anything to bite against, can also start to erupt further out of its socket, a phenomenon called “supraeruption.” These shifts can affect your bite alignment (occlusion), leading to issues with chewing efficiency, uneven wear on other teeth, and even problems with the jaw joint (TMJ). Furthermore, the jawbone in the area where the tooth was lost no longer receives the stimulation from the tooth’s root during chewing, leading to gradual bone loss over time. So, addressing whether Is losing a molar OK? from a functional and long-term oral health perspective: generally, no, it’s not ideal or simply “OK” to live without a permanent molar, especially a first or second molar, without considering replacement options. While you can certainly eat without a molar, particularly if it’s a single tooth loss in the back, your chewing efficiency on that side will be reduced. Forgetting about replacement for an extended period can lead to the aforementioned issues, making future replacement more complex and costly.

It’s important to clarify which molars do you lose versus which are typically extracted. You lose your primary molars (baby molars) as part of normal development. These are replaced by permanent teeth – specifically, the primary first molars are replaced by the first premolars (bicuspids), and the primary second molars are replaced by the second premolars. Permanent molars (first, second, and third/wisdom teeth) are not meant to fall out naturally; if a permanent molar is lost, it’s usually due to disease (like severe decay or gum disease) or trauma, or it is intentionally extracted (like many wisdom teeth). So, addressing Do molars fall out? Yes, baby molars fall out (typically between ages 9-12) to make way for premolars, but permanent molars should not fall out on their own. Their loss indicates a significant dental problem. The question What age do molars come out? specifically refers to these primary molars being shed. As discussed, living without a permanent molar can affect your ability to chew efficiently and can have long-term consequences for the stability of your bite and jawbone. While you might be able to manage Can I eat without a molar? the effectiveness of chewing can be reduced, particularly tough or fibrous foods on that side of the mouth. For these reasons, dentists almost always recommend discussing options for replacing a lost permanent molar to maintain oral health and function over the long term.

What specific issues can affect molar teeth?

Beyond the general dental problems like cavities and gum disease that can strike any tooth, molars, due to their unique shape, size, and position at the back of the mouth, are particularly susceptible to certain issues. Their broad chewing surfaces, covered in pits and grooves, are natural traps for food particles and bacteria, making decay a constant threat, especially in those harder-to-reach areas. One specific concern sometimes encountered is a loose first molar. Why is my first molar loose? This is often a sign of advanced gum disease (periodontitis), where the infection has destroyed the bone and ligaments supporting the tooth root. Trauma, such as a blow to the face, can also cause a tooth to become loose. Less commonly, an abscess at the root tip can also cause mobility. Any noticeable looseness in a permanent tooth is a serious issue and warrants immediate dental attention, as early intervention can sometimes save the tooth.

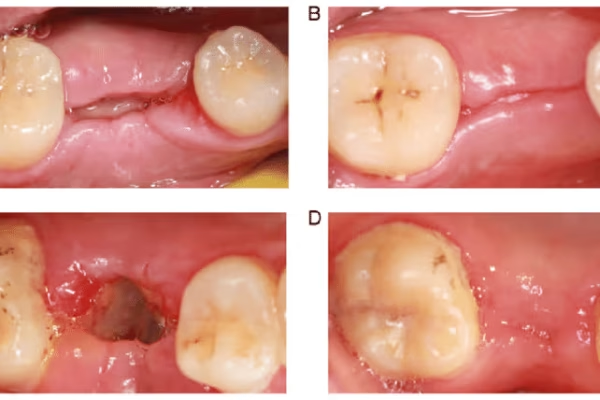

Another condition that specifically impacts the enamel quality of molars (and sometimes incisors) is Molar Hypomineralisation (MH), often shortened to Molar Hypomin. What is Molar Hypomin? The D3 Group, an organisation focused on this condition, defines it as a developmental defect where the enamel of one or more first permanent molars (and sometimes other molars or incisors) is weaker, softer, and more porous than normal. This isn’t caused by decay but rather a disturbance during the tooth’s formation period in early childhood. Affected molars often appear discoloured (ranging from white or cream to yellow or brown) and are highly prone to rapid breakdown and decay, even with good oral hygiene. They can also be extremely sensitive, particularly to temperature changes, making eating and drinking uncomfortable and toothbrushing difficult. Briefly mentioning other issues, molars are also susceptible to cracks and fractures, often from clenching or grinding or biting on hard objects. Because of their multi-rooted structure, diagnosing and treating cracks can be complex. Recurrent decay under old fillings or crowns is also a common problem in molars, as they are subjected to constant chewing forces. Managing these specific molar issues requires careful diagnosis and often involves restorative procedures, diligent home care, and preventative strategies like sealants (to protect the vulnerable chewing surfaces from decay) or custom nightguards (to protect against grinding).

What are the options for replacing a lost molar?

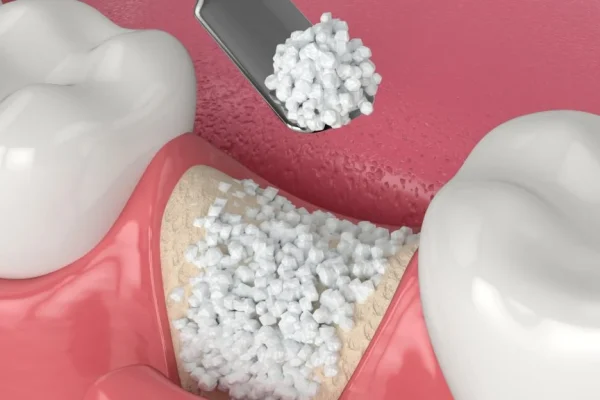

Okay, so we’ve established that losing a permanent molar isn’t ideal and can lead to a cascade of problems down the line. This underscores the significant importance of replacing lost molars. Maintaining a full set of teeth is crucial not only for efficient chewing but also for preventing the shifting of neighbouring teeth, preserving jawbone density, and supporting facial structure. Fortunately, modern dentistry offers several excellent various replacement options for a missing molar. These typically fall into three main categories: dental implants, bridges, and partial dentures. A dental implant is considered the gold standard and the closest thing to a natural tooth. It involves surgically placing a titanium post into the jawbone where the tooth root used to be. After a healing period (osseointegration), a connector (abutment) is attached to the post, and then a custom-made crown is placed on top. Implants are stable, don’t rely on neighbouring teeth for support, and help prevent bone loss. Bridges are fixed prosthetic devices that literally “bridge” the gap created by the missing tooth. They consist of one or more artificial teeth (pontics) held in place by crowns cemented onto the natural teeth adjacent to the gap (abutment teeth). Bridges are a non-surgical option but require altering the adjacent teeth to fit the crowns and don’t prevent bone loss in the extraction site. Partial dentures are removable appliances that contain one or more artificial teeth. They are typically held in place by clasps that attach to neighbouring teeth. Dentures are generally the least expensive option but can be less stable than implants or bridges, need to be removed for cleaning, and don’t prevent bone loss.

Addressing financial considerations is often a major factor in choosing a replacement. What is the cheapest way to replace a back molar? Generally, a partial denture is the most budget-friendly option upfront. A fixed bridge is typically more expensive than a partial denture but less costly than a dental implant. Dental implants are usually the most significant initial investment but can be the most cost-effective in the long run because they are durable, long-lasting, and help preserve bone structure, potentially preventing future dental work needed due to bone loss or shifting teeth. Let’s focus on dental implants for a moment, as they are often the preferred recommendation for single molar replacement when bone density and overall health permit. Is a Molar Dental Implant Right For You? | Colgate® and other resources highlight that molar implants restore full chewing function, look and feel like natural teeth, and don’t require altering adjacent healthy teeth, unlike bridges. They also stimulate the jawbone, preventing the bone loss that occurs after tooth extraction. However, like any surgical procedure, there are Advantages and Risks of a Molar Implant. Advantages include high success rates (around 95-98%), long-term durability, bone preservation, stability, and improved function and aesthetics. Risks are generally low but can include infection at the implant site, injury to surrounding structures (like nerves or blood vessels), sinus problems (for upper implants), or implant failure (though rare). A thorough consultation with a dentist or oral surgeon is essential to determine the best replacement option based on your individual needs, oral health, budget, and preferences.

How to Take Care of Your Molars? Importance and Tips

Given the vital role your molars play – they’re responsible for the majority of the hard work during chewing, helping you process food and contributing significantly to maintaining the height of your bite and overall facial structure – it’s crystal clear Which molar is most important? While all teeth are valuable, the first permanent molars, which erupt early and anchor the back of your bite, are arguably among the most critical and often called the “cornerstones” of the mouth. Losing a first molar can have more profound consequences for your bite than losing, say, a third molar (wisdom tooth). Therefore, dedicating effort to keeping your molars healthy is paramount. How to Take Care of Your Molars? It boils down to consistent, effective oral hygiene practices. Because molars are at the back, they can be harder to reach with a toothbrush, and their grooved surfaces are perfect hiding spots for plaque and food debris.

Here are some practical advice on brushing and flossing techniques specifically for reaching and cleaning molars: When brushing, use a soft-bristled brush and angle it towards the gum line. Use short, gentle back-and-forth or circular motions on the chewing surfaces, making sure to really work the bristles into those pits and fissures. Spend adequate time on the molars at the very back – they often get missed! For flossing, it’s essential daily. Use a piece of floss long enough to comfortably wrap around your index fingers, leaving a few inches in between. Guide the floss gently between the teeth using a sawing motion, then curve it into a ‘C’ shape around the side of the tooth and slide it gently below the gum line. Scrape upwards and downwards a few times on each side of both teeth in the gap. Don’t forget the very back surface of the last molar in each corner of your mouth! Using floss threaders or interdental brushes can be helpful if you have tight spaces or difficulty with traditional floss. Beyond home care, the importance of regular dental check-ups and cleanings for molar health cannot be overstated. Dentists and hygienists can reach areas you might miss, remove hardened plaque (calculus), and spot potential problems like early decay or gum disease in molars before they become painful or severe. They can also recommend preventative measures like sealants, especially for children’s molars shortly after they erupt. Sealants are thin, plastic coatings applied to the chewing surfaces of back teeth to fill in the pits and grooves, creating a smooth surface that’s easier to clean and much less likely to trap bacteria and develop cavities. It’s a simple, effective way to protect those vulnerable areas. Thinking About your molars and their ongoing care needs throughout life is key – they are needed for decades of chewing! So, committing to diligent home care and partnering with your dental team for regular check-ups is the best strategy for ensuring your molars stay strong, functional, and pain-free, highlighting What is the importance of regular care for molars? – it’s the foundation of a healthy, functional bite for life.

What are some common dental procedures performed on molar teeth?

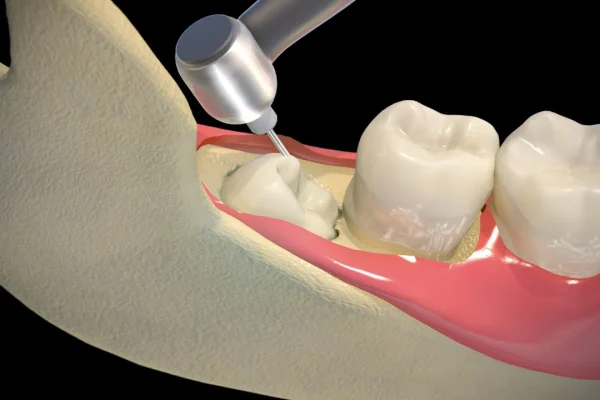

Given the heavy workload and unique anatomy of molars, it’s no surprise that they frequently require dental intervention throughout a person’s life. While routine check-ups and cleanings are essential, molars are often the site for more complex procedures designed to restore function, alleviate pain, or address infection. Introducing the types of dental treatments molars commonly receive: The most frequent procedure is likely a filling, used to repair cavities in the enamel and dentin layers of the tooth. Because molars have deep grooves, even small cavities need prompt attention to prevent them from spreading rapidly. If decay progresses deep enough to infect the pulp (the nerve and blood vessel tissue inside the tooth), a root canal treatment becomes necessary. This procedure involves removing the infected or damaged pulp, cleaning and disinfecting the inside of the root canals, and then filling and sealing the space. Root canals save the tooth structure when the nerve is compromised, avoiding extraction. After a root canal, or when a molar has a large filling, significant decay, or is cracked, a crown (a cap that covers the entire tooth) is often needed to protect the weakened tooth structure, restore its shape, and allow it to withstand chewing forces.

Beyond these common restorative procedures, molars may also require specialized procedures. For example, advanced gum disease affecting the bone around a molar might necessitate periodontal therapy, which could include deep cleaning (scaling and root planing) or even gum surgery. As discussed earlier, extractions, particularly of wisdom teeth, are very common procedures involving molars. For complex extractions or impacted teeth, this might be done by an oral surgeon. In some cases, if a molar has an infection that doesn’t fully resolve with a standard root canal, a minor surgical procedure called an apicoectomy might be performed to remove the tip of the root and seal it. Restoring molars with implants after extraction is also a specialized procedure performed by periodontists or oral surgeons. Sometimes, complex cases require collaboration between different dental specialists, such as an endodontist (for root canals), a periodontist (for gum and bone issues, and implants), or an oral surgeon. For dental professionals seeking in-depth technical information on specific procedures, resources like A practical guide to endodontic access cavity preparation in molar teeth | British Dental Journal provide detailed insights into techniques tailored for molar anatomy, underscoring the complexity and specialized knowledge often required to treat these vital back teeth effectively. Understanding these common procedures can help patients feel more prepared if their molars require treatment beyond routine care.

Frequently Asked Questions About molar teeth

Navigating the world of dental terms and treatments can be a bit much, so let’s wrap things up by tackling some of the most common questions people have about those sturdy grinding machines at the back of their mouth: your molars. Getting clarity on these points can help ease concerns and empower you to take better care of your smile. From identifying which teeth are molars to understanding when they’re supposed to show up and why they might be causing trouble, these FAQs cover the essentials, providing quick, digestible answers to the queries that pop up most often. Knowing the basics is always the first step towards proactive dental health.

What are the 3 molar teeth?

In each quadrant of your mouth (upper right, upper left, lower right, lower left), you have three permanent molars, counting from the front towards the back. These are designated as the first molar, the second molar, and the third molar (which is commonly known as the wisdom tooth). So, across your entire mouth, you have a total of twelve permanent molars if all three in each quadrant are present.

Which teeth are molar?

Molars are the largest, flattest teeth located at the very back of your mouth. They are situated behind the premolars (bicuspids) and are distinguished by their broad chewing surfaces with multiple cusps (points or ridges) designed for grinding food. Unlike the sharp incisors at the front or the pointed canines, molars have a more block-like shape adapted for crushing.

What age do molars come in?

Primary (baby) molars typically erupt between the ages of 1 and 3 years old. Permanent molars come in later: the first permanent molars usually appear around age 6-7, the second permanent molars around age 11-13, and the third permanent molars (wisdom teeth) between 17 and 25 years old. These are general timelines, and there can be some variation.

Why are my molar teeth hurting?

Molar pain can be caused by various issues, including cavities (decay reaching the nerve), gum disease affecting the supporting bone, cracks or fractures in the tooth, impaction (especially wisdom teeth), infection around a partially erupted tooth, a dental abscess, or even referred pain from issues like sinus infections or clenching/grinding (bruxism). It’s crucial to see a dentist to diagnose the specific cause.

Do molars fall out?

Primary (baby) molars do fall out, typically between the ages of 9 and 12, to be replaced by permanent premolars. However, permanent molars are meant to last a lifetime and should not fall out on their own. If a permanent molar becomes loose or falls out, it’s a sign of a significant underlying problem, most commonly advanced gum disease or severe decay/trauma, and requires immediate dental attention.