Table of Contents

ToggleKey Takeaways

- Inlays and Onlays are indirect dental restorations.

- They are used for moderate tooth damage, bridging the gap between simple fillings and full crowns.

- An inlay fits within the chewing surface cusps; an onlay covers one or more cusps for added strength.

- Materials like ceramic, composite, and gold offer enhanced strength and durability compared to large fillings.

- They are a more conservative option than crowns, preserving more natural tooth structure.

What are teeth inlays and onlays and How Do They Restore Your Smile?

At their core, dental inlays and onlays are specialized types of indirect restorations crafted to mend teeth suffering from mild to moderate decay, fractures, or significant wear, particularly impacting the tooth’s chewing surface. Unlike traditional fillings, which dentists sculpt and harden directly within the prepared cavity during a single appointment, inlays and onlays are fabricated outside the mouth, acting as bespoke inserts or covers tailored precisely to the damaged area. This indirect method of creation, usually involving a dental laboratory or sophisticated in-office milling technology, allows for the use of stronger, more durable materials and enables the restoration to achieve an exceptionally accurate fit and contour before it’s ever bonded into place.

An inlay is specifically designed to fit within the confines of the cusps, which are the pointed projections on the chewing surface of your back teeth. Imagine a cavity nestled between these points; an inlay would precisely fill that space, restoring the tooth’s original shape and integrity without extending over the cusps themselves.

An onlay, often referred to as a partial crown, takes things a step further. While also fitting into a cavity, an onlay extends to cover one or more of the tooth’s cusps. This design provides crucial support and reinforcement to weakened cusps that might otherwise be prone to fracture under biting forces. It’s the preferred option when the damage is more extensive, reaching or compromising the cusps, but enough healthy tooth structure remains that a full crown isn’t necessary.

The process generally involves preparing the tooth by removing the decay or damaged portion, taking a precise impression (either physically or digitally), placing a temporary restoration, and then, in a subsequent appointment, bonding the custom-made inlay or onlay securely onto the tooth. This two-step process, while requiring an extra visit compared to a filling, ensures the restoration is fabricated under optimal conditions for maximum strength, fit, and longevity. Various materials, including porcelain, composite resin, or gold, can be used, each offering different benefits in terms of aesthetics, durability, and cost. These restorations effectively repair the tooth by replacing lost structure, sealing the area against further decay, and restoring the tooth’s biomechanical function, allowing it to withstand the forces of chewing more effectively than a large direct filling might. They represent a vital tool in modern restorative dentistry, striking a balance between conservative treatment and robust, long-term tooth repair.

What is the Main Difference Between an Inlay and Onlay?

The fundamental distinction between a dental inlay and an onlay boils down to their coverage area on the tooth’s chewing surface. While both are indirect restorations used to repair damage that’s too extensive for a standard filling but not severe enough for a full crown, where they sit on the tooth is the defining characteristic.

An inlay is designed to fit inside the indentations on the chewing surface of a tooth, specifically within the confines of the cusps (the raised points). Think of it as a restoration that repairs cavities or damage situated between these points, much like a traditional filling but crafted indirectly for superior fit and material properties. The margins of an inlay reside entirely on the chewing surface, bounded by the cusps. If you were to draw a line around the restoration, it would not cross over any of the tooth’s high points. This makes inlays suitable for restoring the central part of the tooth when the surrounding cusps are healthy and structurally sound.

Conversely, an **onlay** is a more extensive restoration. While it also fits into a prepared cavity area, its defining feature is that it extends to cover, or ‘onlay,’ one or more of the tooth’s cusps. This is why they are sometimes called partial crowns. Onlays are indicated when the decay or fracture damage involves a cusp or when a cusp has been weakened and needs protection from biting forces. By covering the cusp, the onlay provides essential support and reinforcement, helping to prevent the cusp from fracturing. The margins of an onlay extend onto the outer surfaces of the tooth (like the cheek or tongue side) as they wrap over the cusps.

In practical terms, the choice between an inlay and an onlay is determined by the dentist based on the specific pattern and extent of the tooth’s damage. If the cavity is small to medium and contained strictly between the cusps, an inlay is often the conservative choice, preserving maximum healthy tooth structure. If the damage is larger, involves a cusp, or if a cusp is significantly weakened, an onlay becomes necessary to provide the required structural integrity and protection against fracture. The preparation for an onlay involves more tooth reduction than for an inlay because the cusps need to be shaped to receive the restorative material. This difference in coverage dictates the clinical application and the amount of tooth structure that needs to be removed or modified during the preparation phase, directly impacting the restorative approach.

How Do Inlays and Onlays Compare to Fillings and Crowns?

Understanding where inlays and onlays fit into the hierarchy of dental restorations requires comparing them to their more common counterparts: direct fillings and full dental crowns. This comparison highlights their unique position as versatile, intermediate solutions for damaged teeth.

Direct Fillings (like composite resin or amalgam) are perhaps the most common type of restoration. They are placed and hardened directly within the prepared cavity during a single dental appointment. They are excellent for repairing small to medium-sized cavities where the tooth structure is relatively intact and the biting forces are not excessively high. Their main advantages are speed, cost-effectiveness, and conservation of tooth structure, as the preparation is usually confined to the decayed area. However, for larger cavities, especially those involving significant portions of the chewing surface or the areas between teeth, direct fillings may not provide adequate strength or durability. They can also shrink slightly upon curing (composite) or involve mercury (amalgam), though modern materials have improved significantly. Large direct fillings, particularly on back teeth, are more susceptible to fracturing or debonding under heavy chewing pressure compared to indirect restorations.

Full Dental Crowns, on the other hand, represent the most extensive type of restoration. A crown covers the entire visible portion of the tooth above the gum line, essentially acting as a protective cap. Crowns are necessary when a tooth is severely damaged by decay or fracture, has undergone root canal treatment (which can weaken the tooth), or needs significant structural reinforcement and protection. Preparing a tooth for a crown involves reducing the tooth on all sides and the top to create a stable base for the crown to fit over. This process removes a substantial amount of healthy tooth structure. Crowns offer maximum support and protection, particularly for teeth subjected to high biting forces, and can also be used to improve the aesthetics of severely discolored or misshapen teeth. However, they are more expensive, require more tooth preparation, and can sometimes lead to issues like sensitivity or gum irritation if not fitted perfectly.

Inlays and Onlays occupy the vital space between direct fillings and full crowns. They are chosen when the damage is too extensive for a durable direct filling but not so severe that it necessitates the significant tooth reduction required for a crown. They are ‘indirect’ like crowns (made outside the mouth) but are ‘partial’ like fillings (don’t cover the whole tooth). By preserving more natural tooth structure than a crown while offering superior strength, durability, and precise fit compared to a large direct filling, inlays and onlays provide a conservative yet robust restorative solution. They are particularly well-suited for restoring back teeth with large cavities or failing fillings where the cusps are either intact (inlay) or need partial coverage and reinforcement (onlay). This makes them a sophisticated choice for preserving tooth longevity and structural integrity.

Are Onlays Better Than Fillings?

When comparing onlays specifically to traditional direct fillings, particularly for repairing moderate to large cavities on posterior (back) teeth, onlays often hold significant advantages in terms of strength, durability, and longevity, leading many dentists and patients to consider them a “better” option in appropriate clinical scenarios. Direct fillings, while quick and cost-effective for smaller cavities, can become compromised when used to restore larger areas or areas under heavy stress. As the size of a direct filling increases, its ability to withstand biting forces diminishes, and it becomes more prone to fracture, leakage, or simply wearing away over time. Furthermore, placing and curing a large composite filling directly in the mouth can be technically challenging to achieve perfect contacts with adjacent teeth and a precise anatomical shape.

Onlays, being indirect restorations, bypass many of these limitations. Because they are fabricated outside the mouth, either in a lab or using in-office milling technology, they can be made from stronger, more durable materials like ceramic or gold, which are cured to their maximum hardness and strength under controlled conditions before being bonded to the tooth. This allows the onlay to bear significantly more occlusal (bitting) force without fracturing or deforming compared to a large direct composite filling. Moreover, the indirect fabrication process results in a restoration with extremely precise margins and anatomical contours. This superior fit minimizes the risk of microleakage at the restoration’s edges, a common pathway for bacteria to cause secondary decay beneath the filling. Crucially, onlays, especially those made from materials like ceramic or gold, provide structural reinforcement to the tooth, particularly when they cover and protect weakened cusps. A large filling placed in a tooth with compromised cusps offers little support, leaving the tooth vulnerable to fracture. An onlay, by capping the cusp(s), helps to hold the tooth together and distribute biting forces more favourably. Therefore, for teeth with damage that extends beyond the very basic, or for replacing large, failing fillings, onlays typically offer a more robust, longer-lasting, and tooth-preserving solution than simply replacing the old filling with another large direct filling. The initial cost and the need for two appointments are trade-offs for this enhanced performance and potential tooth longevity.

What is Better: Crown or Inlay/Onlay?

The question of whether a crown or an inlay/onlay is “better” isn’t about one being universally superior to the other, but rather about which restoration is most appropriate for the specific clinical situation and the extent of the tooth’s damage. It’s a decision guided by the principle of conservative dentistry – doing what is necessary to restore the tooth’s health and function while preserving as much of the natural tooth structure as possible.

A full dental crown is the treatment of choice when a tooth has suffered extensive damage that compromises its structural integrity significantly. This includes cases where a large portion of the tooth structure has been lost due to decay or fracture, teeth that have undergone root canal treatment (which can make them brittle and more susceptible to fracture), teeth with significant cracks extending deep into the tooth structure, or when severe wear has occurred. Preparing a tooth for a crown requires removing a substantial amount of enamel and dentin from all surfaces of the tooth to create space for the crown to fit over. This extensive preparation is necessary to ensure the crown has sufficient bulk for strength and retention. When the remaining tooth structure is too weak or minimal to support a partial restoration like an inlay or onlay, a crown provides the essential full-coverage protection needed to prevent catastrophic failure.

Conversely, inlays and onlays are preferred when a significant amount of healthy tooth structure remains. If the decay or damage is confined within the cusps (inlay) or involves one or a few cusps but leaves the core of the tooth and other cusps largely intact (onlay), these restorations offer a more conservative approach. The preparation for an inlay or onlay involves removing only the decayed or damaged part of the tooth and shaping the cavity/cusp areas to receive the restoration. This preserves far more natural tooth material compared to a crown preparation. By saving healthy tooth structure, inlays and onlays reduce the risk of irritating the tooth’s pulp (nerve) and maintain the tooth’s inherent strength, potentially delaying or even preventing the need for more aggressive treatment like a crown in the future.

Therefore, the “better” choice is the one that provides adequate strength, protection, and restoration while being the least invasive option. A skilled dentist will carefully assess the tooth’s condition, the extent and location of the damage, the strength of the remaining tooth structure, and the forces the tooth will be subjected to determine whether an inlay, onlay, or full crown is the most appropriate and beneficial treatment for the patient’s long-term oral health. Opting for an inlay or onlay when possible aligns with modern dental philosophy which prioritizes preserving as much of the natural tooth as fate will allow.

Is an Onlay Cheaper Than a Crown?

In the vast majority of cases, yes, a dental onlay is typically less expensive than a full dental crown. While both are considered indirect restorations and involve laboratory fabrication (unless done in-office with CAD/CAM technology), the cost difference primarily stems from the amount of material used, the complexity and time involved in the fabrication process, and the extent of tooth preparation required.

Preparing a tooth for a full crown is a more involved procedure than preparing for an onlay. It requires reducing the tooth structure on all sides and the chewing surface to create a stable foundation for the crown to fit over entirely. This means more chair time for the dentist during the preparation visit. Furthermore, the fabrication of a crown in the dental laboratory usually involves more material and a more complex process compared to an onlay, which covers only a portion of the tooth. Lab fees, which are a significant component of the total cost of indirect restorations, reflect this difference in material and labour. For example, a lab constructing a full porcelain or zirconia crown has a different workflow and material usage than crafting a smaller ceramic or composite onlay.

For in-office, single-visit restorations using CAD/CAM technology (like CEREC), the principle often still holds true, though the difference might be less pronounced. While the equipment cost is high for the dentist, the milling time and material blank used for an onlay are generally less than for a full crown. Less preparation time also contributes to lower chair costs compared to a full crown visit.

Another factor is the materials themselves. While both crowns and onlays can be made from various materials (ceramic, composite, gold, zirconia), the amount of material needed is less for an onlay. While gold is usually the most expensive material per unit, a smaller gold onlay might still be less expensive than a large, complex ceramic crown.

The cost of any dental procedure can vary significantly based on factors like geographic location (costs are typically higher in metropolitan areas), the dentist’s fees (reflecting their expertise and practice overheads), the specific material chosen, the size and complexity of the individual restoration, and, crucially, your dental insurance coverage. However, as a general rule of thumb, because an onlay is a partial restoration requiring less tooth reduction and material than a full crown, its cost is usually positioned between that of a large, complex filling and a complete crown, making it a potentially more budget-friendly option when clinically appropriate compared to jumping straight to a crown. It’s always best to get a detailed treatment plan and cost estimate from your dentist before proceeding.

Am I a Candidate for a Dental Inlay or a Dental Onlay?

Determining candidacy for a dental inlay or onlay is a crucial step in the treatment planning process, guided by a thorough examination and diagnosis by your dentist. These restorations are not one-size-fits-all solutions; they are specifically indicated for certain types and extents of tooth damage. Generally, you might be an excellent candidate for an inlay or onlay if your tooth has decay, damage, or a failing existing filling that is too large or extensive to be reliably restored with a direct filling, but not so widespread or severe that it has compromised the tooth’s overall structural integrity to the point where a full crown is necessary.

Think of inlays and onlays as the ideal solution for that ‘in-between’ zone of damage. This often includes teeth with moderate cavities located on the chewing surfaces or between the cusps (suitable for an inlay). You might be a candidate for an onlay if the decay or damage extends to involve one or more of the tooth’s cusps, or if the existing cusp is weakened by cracks or previous extensive filling material and requires reinforcement to prevent fracture under biting forces. They are particularly effective for restoring posterior teeth (premolars and molars) which bear the brunt of chewing forces. Inlays and onlays are also frequently recommended to replace large, aging amalgam fillings that are starting to fail, leak, or show signs of cracking the surrounding tooth structure, as they can provide a stronger, more durable, and potentially more aesthetic replacement while conserving more tooth than a crown.

Another scenario where an inlay or onlay might be recommended is in the case of certain types of tooth fractures. If a cusp has fractured, but the fracture line doesn’t extend below the gum line or significantly into the root, an onlay can often be used to restore the missing part and protect the remaining tooth structure. The key requirement for successful inlay or onlay placement is the presence of sufficient healthy tooth structure to support and retain the restoration. Your dentist will carefully assess the depth of the decay, the strength of the remaining tooth walls and cusps, and the overall health of the tooth’s pulp (nerve) to determine if an inlay or onlay is a viable and appropriate treatment option for your specific situation.

When is a Dental Inlay or Onlay Recommended?

A dental inlay or onlay becomes a top recommendation when a dentist determines that the scope of restorative work required exceeds the capabilities of a standard direct filling but falls short of needing a comprehensive crown. This is particularly true for teeth located in the back of the mouth – the premolars and molars – which are subjected to significant forces during chewing. A prime indication is a tooth with a large cavity that extends beyond the simple surfaces into the main body of the tooth on the chewing surface, or involves the proximal surfaces (between teeth) extensively, making it difficult to achieve a strong, well-sealed, and anatomically correct restoration with a direct filling.

Another common scenario where an inlay or onlay is recommended is for replacing large, compromised existing fillings, such as old amalgam or composite restorations that are breaking down, leaking, or beginning to stress or fracture the surrounding tooth structure. These older, larger fillings might not offer adequate support to the tooth against the forces of chewing, and simply replacing them with another large direct filling might not significantly improve the prognosis or strength of the tooth. An indirect restoration like an inlay or onlay, fabricated from stronger materials and bonded precisely to the tooth, provides superior reinforcement and a better long-term seal compared to another large direct filling.

Furthermore, onlays are specifically indicated when one or more cusps of a tooth are weakened, fractured, or undermined by decay or a large previous filling. Instead of removing the entire tooth structure for a crown, an onlay can be designed to fit into the prepared cavity area and then flow over and cap the compromised cusp(s). This partial coverage reinforces the weakened areas, protecting them from fracturing under the heavy loads experienced during chewing. In essence, an inlay or onlay is recommended when a tooth needs a restoration that offers greater strength, durability, precision, and tooth preservation than a direct filling, but still possesses enough healthy structure to avoid the necessity and invasiveness of a full crown. It’s about choosing the most appropriate restoration to extend the life and function of the tooth conservatively.

Are There Reasons You Might Not Be a Candidate?

While dental inlays and onlays offer excellent restorative benefits, they are not universally suitable for every damaged tooth. Several factors can render you unsuitable for these specific types of restorations, necessitating an alternative treatment like a direct filling or, more often, a full dental crown. One of the primary contraindications is extensive tooth decay or damage that has resulted in a significant loss of tooth structure. If there isn’t enough healthy enamel and dentin remaining to support the inlay or onlay and withstand biting forces, the restoration may fail prematurely by fracturing or debonding, or worse, the remaining weak tooth structure could fracture underneath it.

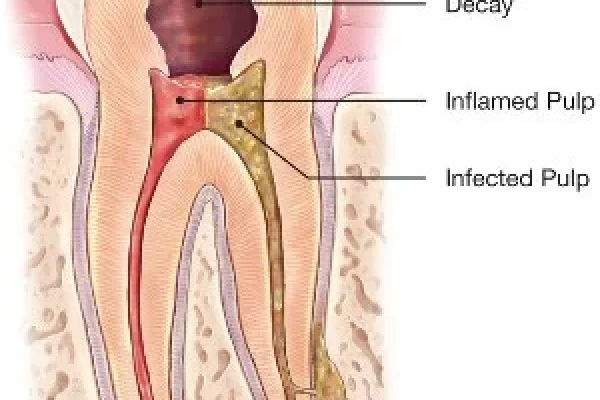

Another reason you might not be a candidate is if the decay has reached the tooth’s pulp chamber, potentially causing irreversible inflammation or infection of the nerve. In such cases, root canal treatment is required. While some teeth that have had root canals can potentially receive onlays (depending on the remaining tooth structure), many require full crowns for maximal protection, as endodontically treated teeth can become more brittle over time and are more susceptible to fracture, particularly in the back of the mouth. Severe teeth grinding or clenching habits (bruxism) can also sometimes preclude the use of inlays or onlays, particularly those made from more brittle ceramic materials. The excessive forces generated by bruxism can overwhelm the restoration or the remaining tooth structure, leading to chips, cracks, or debonding. In cases of severe bruxism, a full crown made from a very strong material like zirconia might be a more durable option, often coupled with a nightguard.

Furthermore, if the restoration is needed in a highly visible area, such as a front tooth (anterior teeth), inlays and onlays are less commonly used compared to posterior teeth. Restoring anterior teeth often requires materials and techniques focused more heavily on intricate aesthetics, and the type of damage in front teeth (often chipping, wear on the edges) might lend itself better to bonding or veneers, or full crowns if damage is extensive. Periodontal health is also critical; if the tooth has significant gum disease or insufficient bone support, the overall prognosis of the tooth needs to be assessed before any type of restoration is placed. Ultimately, the decision relies on a thorough clinical assessment, often involving X-rays, to evaluate the depth of decay, the integrity of the remaining tooth structure, the condition of the roots and surrounding bone, and the forces the tooth will endure. If these factors indicate that an inlay or onlay will not provide a predictable, long-lasting outcome, your dentist will recommend a more appropriate alternative.

What are the Advantages and Disadvantages of Inlays and Onlays?

Choosing any dental restoration involves weighing its potential benefits against its drawbacks, and inlays and onlays are no exception. Positioned between direct fillings and full crowns, they offer a distinct profile of advantages and disadvantages that make them the ideal choice in certain situations but less so in others. On the plus side, one of the standout advantages is their superior strength and durability compared to large direct fillings. Because they are fabricated indirectly from materials like ceramic or gold under controlled conditions, they achieve maximum hardness and integrity before being bonded to the tooth, allowing them to withstand chewing forces far more effectively than bulky fillings molded in place. This robustness translates directly into greater longevity; inlays and onlays often last significantly longer than traditional fillings, providing a durable repair that can function reliably for a decade or more with proper care. Another major pro is tooth preservation. Compared to full crowns, which require substantial reduction of tooth structure, inlays and onlays are conservative restorations, preserving more of your natural tooth. This is beneficial for tooth health and reduces the risk of complications. The indirect fabrication process also allows for excellent fit and marginal seal. The restoration is precisely crafted to fit the prepared cavity and tooth contours, minimizing gaps where bacteria could enter and cause secondary decay, a common failure point for many restorations. Finally, when made from aesthetic materials like ceramic or composite, they can be color-matched to your natural tooth, providing a highly aesthetic, virtually invisible repair.

However, there are downsides. A significant disadvantage is cost. Inlays and onlays are generally more expensive than direct fillings due to the indirect fabrication process involving lab work or expensive in-office milling technology, as well as the higher cost of the materials themselves. The procedure typically requires two dental visits, unlike single-visit fillings. The first visit involves preparation and taking impressions, and the second is for bonding the final restoration. This adds to the time commitment. Patients may also experience some temporary post-operative sensitivity to hot, cold, or pressure after the bonding appointment, although this usually resolves within a few days or weeks. Finally, the preparation and bonding techniques for inlays and onlays are more complex and technique-sensitive than placing a simple filling, requiring a higher level of skill and precision from the dentist. Understanding these pros and cons helps in making an informed decision with your dental professional about whether an inlay or onlay is the right choice for your specific needs and situation.

Pros and Cons of Inlays and Onlays

Delving deeper into the advantages and disadvantages of dental inlays and onlays reveals a compelling case for their use in specific clinical scenarios.

Advantages (Pros):

1. Strength and Durability: This is perhaps their most significant advantage over large direct fillings. Inlays and onlays are fabricated from materials like high-strength ceramics (such as porcelain or zirconia), composite resin, or gold. These materials, particularly ceramic and gold, are significantly stronger and more resistant to wear and fracture than materials used for direct fillings when subjected to the considerable forces of chewing in the back of the mouth. The indirect process allows the material to achieve optimal physical properties before placement. By providing this robust strength, onlays are particularly adept at protecting weakened cusps from breaking, essentially holding the tooth together and distributing biting stresses more favorably across the remaining tooth structure.

2. Tooth Preservation: A core tenet of modern dentistry is minimal intervention. Inlays and onlays excel here compared to full crowns. Preparing a tooth for a crown involves reducing the entire circumference and top surface of the tooth. For an inlay or onlay, preparation is limited primarily to removing the decayed or damaged tissue and shaping the cavity/cusp surfaces. This conserves a far greater amount of healthy enamel and dentin, maintaining the tooth’s natural integrity and potentially reducing the risk of needing more invasive procedures or facing complications down the line.

3. Longevity: Due to their superior strength, durability, and precise fit, inlays and onlays generally boast a longer lifespan than large direct composite or amalgam fillings. With diligent oral hygiene and regular dental check-ups, it’s not uncommon for these restorations to last 10 to 15 years, and often much longer, offering a more enduring repair for moderate damage. Studies on survival rates consistently show favourable outcomes for inlays and onlays over large composite fillings.

4. Precise Fit and Marginal Integrity: The indirect fabrication process allows dental technicians (or in-office milling machines) to create restorations with exceptional accuracy. This results in an inlay or onlay that fits the prepared tooth precisely. This snug fit, combined with advanced dental bonding techniques, creates a tight seal at the margins where the restoration meets the tooth. A well-sealed margin is crucial for preventing microleakage – the seepage of bacteria and saliva into the microscopic gap between the restoration and the tooth – which is a leading cause of secondary decay underneath the restoration.

5. Aesthetics: When made from tooth-colored materials like porcelain, ceramic, or composite resin, inlays and onlays can be meticulously matched to the natural shade of the surrounding tooth structure. This makes them virtually indistinguishable from natural teeth, offering a highly aesthetic solution, especially compared to visible amalgam fillings.

Disadvantages (Cons):

1. Cost: This is often the most significant barrier for patients. Inlays and onlays are considerably more expensive than direct fillings. The higher cost is attributed to the advanced materials used, the technical skill required for both preparation and bonding, and the cost of the indirect fabrication process, whether it involves laboratory fees or the investment in in-office CAD/CAM technology.

2. Procedure Requires Multiple Visits: Typically, placing an inlay or onlay involves at least two dental appointments. The first visit is for tooth preparation, taking impressions, and placing a temporary restoration. The second visit is for bonding the permanent restoration. This contrasts with the single-visit nature of direct fillings, requiring more time commitment from the patient. While single-visit options exist with CAD/CAM, they are not universally available or suitable for all cases.

3. Potential for Post-Operative Sensitivity: It is not uncommon for patients to experience some temporary sensitivity to hot, cold, or pressure after an inlay or onlay is bonded. This sensitivity can be related to the preparation process, the bonding materials used, or the slight initial adjustments the tooth and surrounding tissues make to the new restoration. While usually transient, it can be bothersome for a short period.

4. Technical Complexity: Both the preparation of the tooth for an inlay or onlay and the subsequent bonding procedure are more technically sensitive and require greater precision and skill from the dentist compared to placing a direct filling. Proper moisture control during bonding, precise seating of the restoration, and accurate bite adjustment are critical for the long-term success of the restoration.

In summary, while requiring a higher investment of time and money, the advantages of increased strength, durability, longevity, and tooth preservation make inlays and onlays a highly valuable and often preferred restorative option for teeth with moderate damage, particularly in the load-bearing posterior region of the mouth. The choice ultimately depends on the specific clinical needs and patient priorities.

What Can I Expect During the Dental Inlay or Onlay Procedure?

Undergoing a dental inlay or onlay procedure is typically a multi-step process, usually completed over two appointments, though technological advancements like CAD/CAM (Computer-Aided Design/Computer-Aided Manufacturing) have made single-visit procedures possible in some cases, primarily for ceramic restorations. Let’s walk through the traditional two-visit experience.

Visit 1: Preparation and Impression

Your first appointment will focus on preparing the tooth to receive the inlay or onlay and creating a precise record for its fabrication. The process begins with administering local anesthetic to numb the tooth and the surrounding gum tissue, ensuring you are comfortable and feel no pain during the procedure itself. Once the area is numb, your dentist will carefully remove any existing decay, old filling material, or damaged tooth structure. The remaining healthy tooth structure is then shaped into a specific form. Unlike the relatively simple shape for a basic filling, the preparation for an inlay or onlay is more precise, designed to provide adequate retention and resistance for the indirect restoration, often involving specific angles and depths. The goal is to create a clean, sound base while preserving as much healthy tooth as possible.

After the tooth is meticulously prepared, the next critical step is taking a highly accurate impression of your prepared tooth, as well as the surrounding teeth and the opposing arch. This impression serves as a mold or digital blueprint for the dental lab (or in-office milling unit) to fabricate your custom inlay or onlay. Impressions can be taken using traditional putty-like materials or, increasingly, with digital scanners that create a 3D model of your mouth. The precision of this impression is paramount to ensuring your final restoration fits perfectly. While your permanent inlay or onlay is being made (which typically takes about one to two weeks if sent to an external lab), your dentist will place a temporary restoration in the prepared tooth. This temporary inlay or onlay protects the exposed tooth structure, prevents the surrounding teeth from shifting, and allows you to function reasonably normally in the interim. Before you leave, your dentist will check your bite and provide instructions on caring for the temporary and what to expect.

Visit 2: Bonding the Permanent Restoration

Your second appointment is for placing and permanently bonding the custom-fabricated inlay or onlay. The process begins with removing the temporary restoration and cleaning the tooth thoroughly to remove any temporary cement or debris. Your dentist will then carefully try in the permanent inlay or onlay to verify its fit, ensuring it seats perfectly into or onto the prepared tooth structure, contacts adjacent teeth correctly, and aligns properly with your bite. This ‘try-in’ phase is essential for making any minor adjustments before bonding.

Once the fit is confirmed, the tooth surface is prepared for bonding using special etchants and bonding agents. These materials create a microscopic surface texture and chemical bond that allows the inlay or onlay to adhere securely to the tooth. The restoration itself may also be treated to enhance the bond. The inlay or onlay is then carefully seated and bonded into place using a strong dental cement or resin. For many materials, a special curing light is used to harden the bonding agent, creating a powerful and durable connection between the restoration and the tooth. After the bonding material is fully cured, any excess cement is meticulously removed, and the margins are polished smooth. Finally, your dentist will check your bite again, making any necessary minor adjustments to ensure comfortable and even contact with your opposing teeth when you bite down. This final step is crucial for preventing excessive force on the restoration or causing discomfort. You will then receive instructions on caring for your new restoration.

Is Getting a Dental Onlay Painful?

One of the most common concerns patients have about dental procedures is potential pain. When it comes to getting a dental onlay (or inlay), you can rest assured that the procedure itself is performed with effective local anesthetic, meaning you should feel no pain during the tooth preparation or the bonding process. Before your dentist begins any work, they will numb the tooth and surrounding gum tissue thoroughly. While you might feel a slight pinch from the initial injection, this sensation is momentary, and soon the entire area will be comfortably numb. You’ll feel pressure and vibrations from the dental drill as it removes decay and shapes the tooth, but actual sharp pain should not be present. The preparation phase is designed to be as comfortable as possible within a numb environment.

After the local anesthetic wears off later the same day or the following morning, it is quite normal to experience some degree of post-operative discomfort or sensitivity. This can range from mild aching to sensitivity to hot, cold, or biting pressure, particularly in the first few days or weeks after the final bonding appointment. The tooth’s nerve, or pulp, can become temporarily irritated by the preparation process itself, the chemicals used in the bonding agents, or the presence of a new restoration adjusting within your bite. Sensitivity to temperature is particularly common and usually subsides as the tooth settles down. Discomfort when biting might indicate that the restoration is slightly high in your bite and requires a minor adjustment by your dentist, which is a quick and painless procedure.

For most patients, any post-procedure discomfort is minimal and can be easily managed with over-the-counter pain relievers such as ibuprofen or acetaminophen. Your dentist may recommend a specific pain management protocol if necessary. Persistent or severe pain, pain that worsens over time, or pain that occurs spontaneously without stimulation (like biting or temperature changes) is not typical and warrants contacting your dentist immediately, as it could indicate a less common issue requiring attention. However, experiencing some degree of transient sensitivity or mild discomfort is a normal part of the healing process after receiving an inlay or onlay.

How Long Does the Onlay/Inlay Procedure Take?

The total time required for a dental inlay or onlay procedure spans two appointments for the traditional method, with each visit varying in length depending on the complexity of the case, the location of the tooth, and the specific techniques and technologies used by your dentist.

Visit 1 (Preparation and Impression): This appointment is generally the longer of the two. After the administration and onset of local anesthetic, the dentist must meticulously remove all decay or old filling material and then precisely shape the remaining healthy tooth structure to prepare the cavity for the inlay or onlay. This preparation requires careful attention to detail to ensure the final restoration will fit securely and function correctly. Following the preparation, the dentist or assistant takes the impressions (either digital or traditional), which is another step requiring accuracy and a few minutes of time. Finally, a temporary restoration must be fabricated and cemented into place to protect the prepared tooth between appointments. Accounting for numbing time, preparation, impression taking, and temporary placement, this first visit typically takes anywhere from 60 to 90 minutes, sometimes slightly longer for particularly complex cases involving multiple surfaces or challenging tooth anatomy.

Visit 2 (Bonding the Permanent Restoration): The second appointment is usually shorter and focuses on placing the finished custom-made inlay or onlay. This visit involves removing the temporary restoration, cleaning the tooth, trying in the permanent restoration to check the fit and bite, preparing the tooth surface for bonding, bonding the inlay or onlay securely with dental cement or resin, removing excess material, polishing the margins, and performing final bite adjustments. Because the restoration is already fabricated to fit, this appointment is generally more streamlined. It typically takes 30 to 60 minutes from start to finish.

So, while the total procedure involves two appointments spread over one to two weeks (to allow for lab fabrication), the actual chair time for the patient is split between these two visits. It’s important to note that if your dentist offers single-visit CAD/CAM technology, both the preparation, fabrication (milling), and bonding can often be completed in a single extended appointment, which might range from 90 minutes to 2.5 hours or even longer depending on the case and technology. This option saves a second trip and eliminates the need for a temporary restoration, but the total time in the chair during that one visit can be longer than either of the two separate appointments in the traditional method. Always confirm with your dental office how long they estimate each appointment will take for your specific procedure.

Can a Dental Inlay or Onlay Be Done in One Visit?

Yes, in many cases, a dental inlay or onlay can indeed be completed in a single visit, thanks to advancements in CAD/CAM (Computer-Aided Design/Computer-Aided Manufacturing) technology, particularly systems like CEREC (Chairside Economical Restoration of Esthetic Ceramic). This technology allows dentists equipped with the necessary milling unit and design software to prepare the tooth, design the restoration digitally, fabricate it right there in the office while the patient waits, and then immediately bond it into place, all within one appointment.

The process in a single-visit scenario differs slightly from the traditional two-visit approach mainly in the fabrication phase. After the tooth is prepared and all decay or old filling material is removed, instead of taking a physical impression to send to an external lab, the dentist uses a special intraoral scanner to create a highly accurate digital 3D image of the prepared tooth and surrounding areas. This digital model is then loaded into specialized CAD software, which the dentist uses to design the inlay or onlay on a computer screen, ensuring it fits the preparation precisely, has the correct anatomical contours, and integrates properly with the patient’s bite.

Once the design is finalized, the data is sent wirelessly to an in-office milling machine. This machine carves the designed restoration out of a block of restorative material, typically a high-quality ceramic. The milling process can take anywhere from 10 to 20 minutes, during which time the patient can relax. After milling, the restoration may undergo some finishing steps, such as polishing or staining/glazing (which might involve a brief firing in a small oven to enhance aesthetics and strength). Finally, once the restoration is ready, it is tried in, adjusted if needed, and then permanently bonded to the tooth using strong dental adhesives, just as in the second visit of the traditional process.

The primary advantage of a single-visit procedure is convenience; it saves the patient a second trip to the dentist and eliminates the need for a temporary restoration, which can sometimes be uncomfortable or prone to coming off. However, this technology is not available in all dental practices, and the materials currently used with in-office milling (primarily ceramics and composites) might not always be the ideal choice for every clinical situation compared to, say, a lab-fabricated gold onlay. Also, for very complex or extensive restorations, some dentists may still prefer the precision and material options offered by a traditional dental lab. So, while single-visit inlays and onlays are a fantastic option when available and appropriate, it’s a capability that varies from practice to practice.

Can Dental Inlays or Onlays Fall Off or Crack?

While dental inlays and onlays are designed to be highly durable and securely bonded to the tooth, providing a robust and long-lasting restoration, like any dental restoration, they are not entirely immune to failure. Yes, in certain circumstances, a dental inlay or onlay can potentially fall off (debond) or crack. However, these occurrences are generally less common compared to the failure rate of large traditional direct fillings, especially when the inlay or onlay is properly placed and cared for.

Debonding (Falling Off): Inlays and onlays are attached to the tooth using a strong dental bonding process involving adhesives and cements. The strength of this bond is crucial for the restoration’s stability. Failure of the bond can occur due to several reasons. Moisture contamination during the bonding procedure can significantly weaken the adhesive strength. Insufficient preparation of the tooth surface, using incompatible bonding agents with the restorative material, or premature exposure to chewing forces before the bonding material has fully cured can all lead to a compromised bond. In some cases, extreme or unusual biting forces, or trauma to the mouth, can also overwhelm even a well-executed bond, causing the restoration to become loose or fall off. If an inlay or onlay does debond, it’s important to contact your dentist immediately. If the restoration is intact and the tooth structure underneath is healthy, it can often be cleaned and re-bonded.

Cracking (Fracture): Fractures can occur in the inlay or onlay restoration itself, or in the surrounding tooth structure. The restoration material’s resistance to fracture depends on the material chosen (ceramic can be more prone to brittle fracture than gold, for example, especially if too thin), its thickness, and the forces it’s subjected to. Excessive biting forces, such as those from clenching or grinding teeth (bruxism) without the protection of a nightguard, can generate stresses that exceed the material’s strength, leading to chips or cracks in the restoration. Trauma to the mouth (e.g., a blow to the face) can also cause fracture. Furthermore, if the underlying tooth structure wasn’t strong enough to support the restoration (either due to insufficient healthy tooth remaining or underlying cracks), the tooth itself could fracture, potentially taking the inlay or onlay with it. Fractures can also sometimes occur if the bite is not perfectly adjusted, leading to concentrated forces on a specific point of the restoration. Small chips might be polished or repaired, but larger cracks often necessitate the replacement of the inlay or onlay, potentially with a crown if the tooth structure is now further compromised. While these issues are possible, they highlight the importance of proper diagnosis, meticulous technique during placement, appropriate material selection based on the clinical situation, and good patient habits (like wearing a nightguard if recommended) to maximize the lifespan and integrity of the restoration.

What to Expect Immediately After Getting an Inlay/Onlay?

Immediately after your permanent inlay or onlay is bonded into place and your dentist has made the final adjustments, there are several sensations and considerations you should be aware of. If local anesthetic was used for the bonding appointment, your mouth will remain numb for a few hours. You should be cautious not to chew on the numb side to avoid accidentally biting your cheek, lip, or tongue.

Once the numbness wears off, the most common sensations you might experience are temporary sensitivity and a feeling that your bite is “different.” Sensitivity to temperature (hot and cold) or biting pressure is quite normal in the days and sometimes weeks following the procedure. This occurs because the tooth’s nerve may have been slightly irritated by the preparation process, the bonding materials, or the temporary trauma of the procedure itself. This sensitivity usually gradually diminishes as the tooth heals and adapts to the new restoration. If the sensitivity is severe, persistent, or increases over time, contact your dentist.

Your bite might feel slightly off or “high” initially, even after the dentist has adjusted it. This is often due to your muscles remembering the old bite configuration. If, after a day or two, it still feels like you are biting on the new restoration first or that it’s preventing your other teeth from coming together comfortably, you should call your dentist for a bite adjustment. This is a simple procedure where the dentist polishes down tiny high spots on the restoration or adjacent teeth.

You might also wonder, “Why does my onlay feel rough?”. This could be due to a tiny bit of excess bonding cement that wasn’t perfectly smoothed away, or perhaps the edge of the restoration feels different to your tongue than your natural tooth surface. Usually, this is minor and either wears smooth quickly or can be polished by your dentist at a follow-up appointment if bothersome.

Regarding eating and chewing: “Can I eat after an inlay?” and “How long after onlay can I eat?”. It’s generally advised to wait until the local anesthetic has completely worn off to avoid injury. After that, you can typically start eating normally. However, it’s prudent to avoid very hard, sticky, or chewy foods on the restored tooth for the first 24 hours while the bond reaches its maximum strength. After this initial period, the restoration should be strong enough to handle normal chewing forces.

“Can I brush my teeth after inlay?” Yes, absolutely. You should resume your normal excellent oral hygiene routine immediately after the procedure. Brushing and gentle flossing around the restored tooth are essential for keeping the margins clean and healthy. “Can you chew gum with an onlay?” While you can chew gum, it’s often advisable to exercise caution, especially with very sticky types of gum, as they could potentially pull or stress the margins of the restoration, particularly if the bond isn’t fully mature or if there are any pre-existing issues.

Overall, expect a period of adjustment. Most immediate post-operative sensations are temporary and resolve as your mouth adapts to its newly restored state.

Can Dental Inlays or Onlays Be Removed?

Yes, dental inlays and onlays can definitely be removed by a dentist if necessary. While they are intended to be permanent restorations, bonded securely to the tooth for long-term function, there are clinical situations where their removal becomes necessary. This could be due to the need for repair or replacement if the inlay or onlay itself fails (e.g., fractures, debonds, or shows significant wear), or if a problem develops with the underlying tooth structure, such as new decay forming around the margins (secondary decay), a crack developing in the tooth, or the need for root canal treatment.

Removing an inlay or onlay is a deliberate procedure performed by the dentist, unlike a direct filling that might simply fall out if the bond fails. The process typically involves using a dental drill to carefully cut through the restoration material. The dentist must be precise to remove the inlay or onlay without causing unnecessary damage to the remaining healthy tooth structure underneath. Depending on the material of the restoration and its size, the dentist might section it into smaller pieces to facilitate removal. Once the restoration is removed, the dentist can then address the underlying issue – whether it’s cleaning out secondary decay, assessing a tooth fracture, or gaining access to the pulp chamber for root canal therapy.

After the underlying problem is treated, the tooth will then require a new restoration. This might be a new inlay or onlay if sufficient healthy tooth structure remains, or it might necessitate a full crown if the removal process and treatment of the underlying issue have further compromised the tooth’s integrity. In some cases, if the tooth is severely damaged after removal and treatment, extraction might even be the only remaining option, followed by tooth replacement like a bridge or dental implant.

It’s important to understand that the removal of an inlay or onlay is not a sign of failure of the initial treatment if it occurs many years after placement. All dental restorations have a lifespan, and eventual replacement is often necessary due to wear, changing oral conditions, or the development of new issues. The ability to remove the restoration allows the dentist to access and treat the underlying tooth, preserving the tooth itself if possible and placing a new restoration.

What Problems Can Arise with Dental Inlays and Onlays?

While dental inlays and onlays are generally successful and long-lasting restorations, like all medical and dental procedures, they are not without potential complications or issues that can arise, either shortly after placement or years down the line. Being aware of these potential problems is important for patients, so they know what to watch for and when to contact their dentist.

One of the most common issues experienced is **post-operative sensitivity**. As mentioned earlier, sensitivity to hot, cold, or biting pressure is quite typical in the days or weeks following the bonding of the permanent restoration. While usually transient, in some cases, it can persist longer or be more severe, potentially indicating inflammation of the tooth’s nerve (pulp) due to the preparation depth, the bonding process, or an unresolved bite issue.

Another potential problem is the development of secondary decay (also known as recurrent decay). Although the precise fit of inlays and onlays is designed to minimize gaps, microscopic leakage can still occur over time, especially if oral hygiene is inadequate or if the margins of the restoration are not perfectly sealed. Bacteria can then infiltrate the area between the restoration and the tooth, leading to new decay forming beneath the inlay or onlay. This often requires removal of the restoration to treat the decay and placement of a new, potentially larger, restoration.

Fracture of either the restoration itself or the surrounding tooth structure is also a possibility. While strong, the materials used for inlays and onlays, particularly ceramics, can be brittle and susceptible to fracture under excessive or unusual biting forces, such as from clenching or grinding, or from biting down unexpectedly hard on something. If the underlying tooth structure was already weakened (despite the dentist’s assessment), it could also be prone to fracturing around or under the restoration.

Less commonly, the **debonding** or loosening of the inlay or onlay can occur, where the adhesive bond between the restoration and the tooth fails, causing the restoration to feel loose or fall out entirely. This can happen due to moisture contamination during bonding, insufficient bond strength, or overwhelming occlusal forces. An improperly adjusted bite can also cause localized excessive forces that stress the bond or the restoration itself. Problems can also include **marginal discoloration** over time, especially with composite inlays/onlays, or **wear** of the restoration material or the opposing tooth if there are material compatibility issues or bite discrepancies. While these potential problems exist, they are not guarantees of failure and proper case selection, meticulous technique, good oral hygiene, and regular dental check-ups significantly reduce the likelihood of their occurrence.

Why Does My Tooth Hurt After an Inlay/Onlay?

Experiencing discomfort or pain in a tooth after it has received a new inlay or onlay is a relatively common post-operative symptom, and understanding the potential reasons behind it can alleviate anxiety and help you know when to seek further dental attention. Often, the discomfort is transient and resolves on its own within a few days or weeks as the tooth recovers from the procedure. The sensation of pain can manifest in different ways, such as sensitivity to hot, cold, pressure, or spontaneous aching.

Most frequently, post-operative pain is due to **transient pulpal inflammation**. The pulp, or nerve tissue within the tooth, can become irritated by the process of tooth preparation, which involves removing decay, shaping the tooth, and using dental instruments that generate heat and vibration. Even with water coolant and careful technique, this can sometimes irritate the pulp. The deeper the decay or preparation, the closer the work gets to the pulp, increasing the potential for irritation. Sensitivity to cold, and sometimes hot, is a classic symptom of pulpal inflammation, particularly in the initial period after the restoration is bonded.

The **bonding process itself** can also contribute to sensitivity. The materials used, including etchants (acids that prepare the tooth surface) and bonding agents, can cause a temporary reaction in the underlying dentin and pulp. Modern bonding systems are biocompatible, but a degree of transient sensitivity is sometimes an unavoidable side effect, often manifesting as sensitivity to temperature or air.

An **improperly adjusted bite** is another frequent cause of pain, particularly pain experienced when biting or chewing. If the new inlay or onlay is even slightly “high” compared to your other teeth, it will bear excessive force when you bite down. This overload puts undue stress on the tooth and the restoration, leading to pain or discomfort. A quick bite adjustment by your dentist to ensure the forces are distributed evenly is usually sufficient to resolve this type of pain.

Less commonly, pain could signal a more significant issue. This includes the possibility of a **pre-existing crack** in the tooth that wasn’t fully evident before the restoration but is now aggravated by the forces transmitted through the inlay or onlay. New secondary decay developing under the restoration (though less likely shortly after placement) can also cause sensitivity or pain as it progresses towards the pulp. In rare cases, if the pulp was severely irritated during preparation or was already compromised by the original decay, the tooth might develop irreversible pulpitis, which could require root canal treatment to resolve the pain.

It’s crucial to distinguish between mild, temporary sensitivity that gradually improves, and severe, persistent, or worsening pain, spontaneous pain (without stimulation), or pain specifically on biting that doesn’t resolve after a few days. While some discomfort is normal, contact your dentist if you are concerned, if the pain is severe, or if it doesn’t improve within the expected timeframe, so they can evaluate the tooth and determine the cause.

What is the Most Common Failure of Inlay/Onlay?

While inlays and onlays are known for their durability and longevity compared to direct fillings, they are not impervious to failure over their lifespan. Identifying the most common failure mode helps understand the importance of proper technique, material selection, and ongoing patient care. Among the potential issues, secondary decay at the margins is frequently cited as a primary reason for the long-term failure and eventual need for replacement of dental inlays and onlays.

Secondary decay occurs when new cavities form around the edges (margins) of the restoration, right where the inlay or onlay meets the natural tooth structure. While indirect restorations aim for a precise fit, microscopic gaps inevitably exist at this interface. These margins are vulnerable areas where plaque and bacteria can accumulate. If oral hygiene is not meticulous, bacteria can produce acids that demineralize the tooth structure adjacent to the restoration, initiating a new cavity that progresses underneath the inlay or onlay. The presence of microleakage – the slow seepage of oral fluids and bacteria into the marginal gap – facilitates this process. While bonding agents create a seal, this seal can degrade over time, especially under constant exposure to oral environment and stress.

Another significant failure mode is **fracture**, which can involve either the restoration material itself or the surrounding tooth structure. The risk of fracture is influenced by the material chosen (ceramic restorations, for example, can be more prone to brittle fracture than gold, especially if too thin or subjected to high, unfavorably directed forces), the size and design of the restoration (larger restorations covering more cusps are under more stress), and the biting forces exerted on the tooth. Severe grinding or clenching habits (bruxism) are major contributors to fracture. For ceramic onlays specifically, fracture of a covered cusp or the body of the restoration is a well-recognized failure mode if occlusal forces are high or the design is inadequate.

While debonding (the restoration coming loose) can occur, particularly early on if the bonding protocol was compromised, it is often considered less frequent in well-executed cases than marginal breakdown leading to decay or eventual fracture after years of service. Therefore, maintaining excellent oral hygiene, ensuring the bite is properly adjusted, using a nightguard if you clench or grind, and attending regular dental check-ups for professional cleaning and monitoring are critical steps in preventing secondary decay and other issues, thereby maximizing the lifespan of your inlay or onlay and preserving the underlying tooth. Your dentist will routinely check the margins and integrity of your restorations during your check-ups.

How Long Do Dental Inlays and Onlays Typically Last?

The longevity of dental inlays and onlays is one of their most attractive features, positioning them as a durable and worthwhile investment in oral health, generally outperforming traditional direct fillings. While it’s impossible to give an exact expiration date, these indirect restorations are designed to last for many years, often exceeding a decade and frequently providing functional service for even longer.

The typical lifespan cited for dental inlays and onlays ranges from **10 to 15 years**. However, numerous clinical studies tracking the survival rates of these restorations show that with proper care, materials, and technique, many inlays and onlays can and do last for 20 years or more. This extended lifespan compared to large composite or amalgam fillings is attributed to the superior strength, durability, and precise fit achieved through the indirect fabrication process and the use of high-quality materials.

Several factors significantly influence the actual lifespan of an individual inlay or onlay:

1. Material Choice: As discussed previously, the material plays a big role. Gold restorations are historically known for their exceptional longevity due to their durability, resistance to wear, and ability to maintain a precise marginal seal over time. High-strength ceramics like zirconia and lithium disilicate also offer excellent durability and can provide many years of service, though their long-term performance data (especially for newer materials) is still accumulating compared to gold. Composite inlays/onlays are generally considered durable but may not last quite as long as gold or premium ceramics under heavy stress.

2. Oral Hygiene and Diet: Diligent brushing and flossing are paramount to prevent secondary decay at the margins of the restoration, which is a leading cause of failure. Limiting sugary and acidic foods and drinks also reduces the risk of decay.

3. Biting Forces and Habits: The amount of stress placed on the restoration during chewing is critical. Teeth in the back of the mouth (molars) generally experience higher forces. Habits like clenching or grinding teeth (bruxism) can significantly reduce the lifespan of an inlay or onlay (especially ceramic) by increasing the risk of fracture or wear; wearing a nightguard can help mitigate this.

4. Location and Size of Restoration: Inlays confined within the cusps may experience different forces than onlays covering multiple cusps. The size of the restoration and the amount of remaining healthy tooth structure also impact longevity; teeth with more inherent strength are better able to support the restoration over time.

5. Quality of Fabrication and Bonding: The skill of the dental technician or the precision of the milling unit in fabricating the restoration, coupled with the dentist’s meticulous technique during tooth preparation and bonding, are fundamental to the restoration’s success and longevity. A precise fit and strong bond are essential.

6. Regular Dental Check-ups: Routine visits allow the dentist to monitor the condition of the inlay or onlay, check for early signs of wear, leakage, or decay, assess the bite, and provide professional cleaning, addressing minor issues before they become major problems.

While 10-15 years is a reasonable expectation, with ideal conditions and excellent care, the lifespan of your dental inlay or onlay can easily extend beyond this, making it a valuable long-term solution for restoring damaged teeth conservatively.

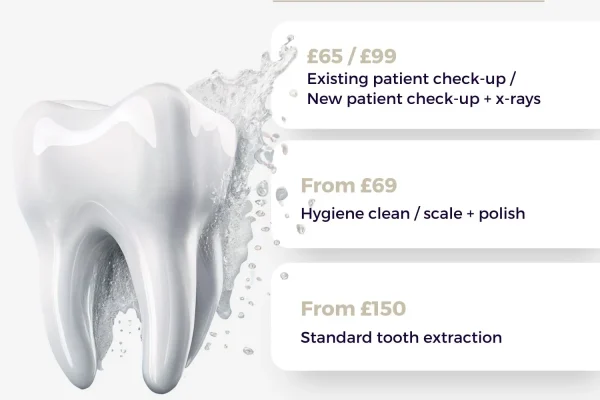

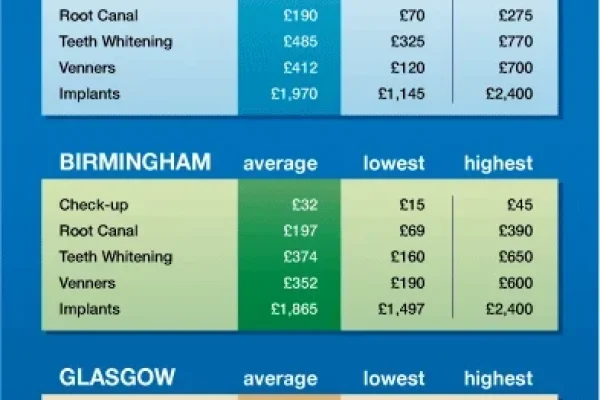

How Much Does a Dental Inlay or Onlay Cost?

The financial investment required for a dental inlay or onlay is a significant factor for patients when considering their treatment options. As indirect restorations, crafted outside the mouth for precision and durability, inlays and onlays carry a higher price tag than standard direct fillings but are typically less expensive than full dental crowns. However, pinning down an exact cost is challenging, as prices vary widely based on numerous influencing factors.

As a general guideline, in the United States, the cost for a single dental inlay or onlay can typically range from $600 to $1,500 or more per tooth. This is a broad range, and the actual cost you pay will depend heavily on the specifics of your case and where you live. For comparison, a large direct composite filling might cost between $200 and $500, while a full crown might range from $800 to $2,500 or more. So, inlays and onlays indeed sit in the middle, reflecting their intermediate complexity and cost of fabrication.

The primary reasons for this cost difference compared to direct fillings are the indirect fabrication process, the materials used, and the increased technical demands of the procedure. Unlike a filling placed and hardened during one appointment, inlays and onlays require either sending impressions to a dental lab for custom fabrication (involving lab fees for technician time, materials, and overhead) or utilizing expensive in-office CAD/CAM milling technology. Both processes involve specialized equipment and skilled labor that add to the overall cost. Furthermore, inlays and onlays often employ higher-strength, more expensive materials like ceramics or gold compared to the composite or amalgam used in direct fillings.

Several key factors specifically influence where within that $600 to $1,500+ range your cost might fall:

1. Material Choice: The type of material used has a substantial impact. Gold is generally the most expensive due to the cost of the metal and casting techniques. Ceramic (porcelain, Emax, Zirconia) is typically the next most expensive, reflecting the material cost and complex processing or milling. Composite is usually the least expensive indirect option.

2. Size and Complexity: Larger restorations covering more tooth surface or multiple cusps require more material and longer fabrication/design time, increasing the cost. Teeth with complex anatomy or challenging access can also increase chair time and cost.

3. Fabrication Method: Whether the restoration is made in an external dental lab or milled in-office via CAD/CAM technology influences the cost structure (lab fee vs. technology overhead).

4. Geographic Location: Costs for dental services vary significantly based on the regional cost of living and the overhead expenses of practices in different areas.

5. Dentist’s Fees: Fees reflect the dentist’s experience, expertise, the technology available in the practice, and overall practice overhead.

6. Dental Insurance Coverage: Your individual dental insurance plan is a critical determinant of your out-of-pocket expense. Coverage levels for inlays and onlays vary; some plans cover them at a similar percentage to fillings, while others may cover them differently or have specific limitations.

Before proceeding with treatment, your dentist will provide a detailed treatment plan and cost estimate specific to your case, which you can then verify with your insurance provider to understand your expected out-of-pocket expense.

What Factors Influence the Cost?

Breaking down the cost of dental inlays and onlays reveals a combination of clinical, material, and logistical elements that contribute to the final price. Understanding these factors can help you appreciate why the cost differs from a simple filling and why it varies between different cases and dental practices.

1. Choice of Material: As the foundational component of the restoration, the material is a primary cost driver. Gold, due to its intrinsic value and the specific laboratory process required for casting, is consistently the most expensive option. Ceramic materials, such as porcelain, pressed ceramics like Emax, and high-strength zirconia, follow closely, with costs varying depending on the specific type of ceramic (e.g., Zirconia material blocks can be expensive, as also can the lab process for layering aesthetic porcelains). Composite resin, while also available as an indirect restoration, is typically less expensive than ceramic or gold, reflecting the lower cost of the raw material itself and potentially less complex processing.

2. Size and Complexity: The larger the area the inlay or onlay needs to cover, the more material and fabrication time are required. An onlay covering multiple cusps is inherently more complex to design and fabricate than a small inlay fitting into a confined space between cusps. Restorations involving restoring contact points with adjacent teeth or requiring intricate shaping also add to the complexity and thus the cost. The amount of remaining tooth structure can also influence complexity; restoring a tooth with minimal healthy structure or complex anatomy can be more challenging.

3. Fabrication Method and Location:

* Dental Laboratory: (Traditional method) If your dentist uses a traditional dental lab, the cost includes a fee from the lab for the technician’s work, materials, and overhead. Lab fees vary widely based on the lab’s quality, specialization (e.g., high-end aesthetic work costs more), location, and the complexity of the case.

* In-Office CAD/CAM: (Single-visit method) Practices with CAD/CAM technology (like CEREC) fabricate the restoration on-site. While this eliminates the lab fee and second appointment, the practice has significant capital investments in the equipment (scanners, mills, furnaces) and software, as well as the ongoing cost of material blocks. The cost you pay reflects these technology overheads and the ability to complete the restoration in a single visit, which saves the dentist time across appointments but requires a longer single appointment.

4. Dentist’s Experience and Fees: A highly experienced dentist with specialized training in cosmetic or restorative dentistry, particularly with indirect restorations and advanced bonding techniques, may charge higher fees reflecting their expertise and the quality of care provided. Practice overheads (rent, staff salaries, insurance, and equipment maintenance, etc.) in a particular geographic area also influence the fees charged.

5. Geographic Location: Dental service costs vary significantly by region and even neighborhood within a city, reflecting differences in the cost of living, business expenses, and market demand.

6. Need for Ancillary Procedures: Occasionally, additional procedures might be needed alongside the inlay or onlay, such as pin placement for added retention (less common now with strong bonding), minor gum contouring, or necessary preliminary treatments for underlying issues, all of which would add to the total cost.

By combining the cost of the material, the complexity of the specific restoration, the fabrication method (lab vs. in-office), the dentist’s fee, and the practice location, the final cost for a dental inlay or onlay is determined. It’s a cost that reflects the precision, durability, and tooth-preserving benefits these advanced restorations offer.

Why Are Inlays and Onlays More Expensive Than Fillings?

The higher cost of dental inlays and onlays compared to direct fillings (like composite or amalgam) is a straightforward reflection of the increased complexity, precision, materials, and labor involved in creating and placing them. While a direct filling is essentially sculpted and cured directly in the tooth during one appointment, inlays and onlays are custom-crafted outside the mouth and then bonded into place, a process that introduces several cost-increasing factors.

1. Indirect Fabrication Process: This is the most significant difference. Direct fillings are ‘direct’ – placed right into the cavity. Inlays and onlays are ‘indirect’ – made separate from the tooth based on an impression or scan. This requires either sending the case to a dental laboratory, which charges a fee for the materials, equipment, and skilled technician labor involved in fabricating the custom restoration, or using expensive in-office CAD/CAM technology which represents a large capital investment for the dental practice. These lab fees or technology costs are factored into the patient’s bill.

2. Material Cost and Quality: While direct fillings use composite resin or amalgam, inlays and onlays often utilize materials that are inherently more expensive per unit, such as high-strength ceramics (porcelain, zirconia) or gold alloys. These materials are chosen for their superior durability, strength, and ability to maintain precise margins over the long term, properties often necessary for restoring back teeth under heavy chewing forces – but they come at a higher price point than standard filling materials.

3. Increased Procedure Complexity and Chair Time: The process of preparing a tooth for an inlay or onlay is more intricate and precise than preparing for a simple filling. It involves creating specific shapes, angles, and retention forms that require more skill and chair time from the dentist during the preparation visit. Furthermore, placing an inlay or onlay typically involves two appointments (preparation/impression and bonding), doubling the appointment count compared to a single-visit filling. While a single-visit CAD/CAM process exists, the single appointment is usually longer and involves the dentist managing both the clinical work and the digital design/milling process. This increased complexity and chair time across visits (or in one longer visit) contributes to the higher fee.

4. Technical Skill and Precision: Both the preparation of the tooth and the bonding of the inlay or onlay require a higher level of technical skill and precision from the dentist compared to placing a standard filling. The successful outcome and longevity of these restorations depend heavily on meticulous execution, including precise fit, careful isolation during bonding, and accurate bite adjustment. The cost reflects this advanced level of dental artistry and technical expertise.

In summary, the higher cost of inlays and onlays stems from them being custom, laboratory-fabricated (or in-office milled), high-strength restorations that require more complex procedures and materials than standard fillings. Patients are essentially paying for the enhanced durability, longevity, precise fit, and tooth-preserving benefits that these indirect restorations provide compared to a simpler, less costly direct filling, particularly for larger areas of damage.

What Materials Are Used for Dental Inlays and Onlays?

Dental inlays and onlays are fabricated from materials chosen for their strength, durability, aesthetics, and biocompatibility, designed to withstand the forces of chewing and blend seamlessly with the natural tooth structure. The selection of the material is a critical decision, influenced by the location of the tooth, aesthetic considerations, biting forces, the amount of tooth structure remaining, and patient preferences. The most commonly used materials fall into three main categories: ceramics, composite resins, and gold alloys.

1. Ceramic: This is a broad category encompassing various types of porcelain and glass-ceramics, offering excellent aesthetics due to their ability to be color-matched and possess natural translucency similar to tooth enamel. Ceramic inlays and onlays are strong, durable, and resistant to staining. Different types offer varying properties:

* Feldspathic Porcelain: The most aesthetic, often used for veneers, but can be more brittle. Less common for load-bearing onlays.

* Leucite-reinforced or Lithium Disilicate (e.g., Emax): Stronger than traditional porcelain, offering good aesthetics and higher resistance to fracture. A very popular choice for both inlays and onlays, including those done via CAD/CAM.

* Zirconia: An extremely strong and durable ceramic material, often used for full crowns, but increasingly used for onlays, especially in areas requiring maximum strength like posterior molars. Less translucent than other ceramics, making it less aesthetic in highly visible areas, but exceptional for durability.