Key Takeaways

-

- Dental trauma is any physical injury to the teeth or supporting structures (gums, ligaments, bone).

-

- Causes are varied, commonly from falls, sports, and accidents.

-

- Symptoms include pain, bleeding, swelling, and visible damage like chips, cracks, or displacement.

-

- Immediate first aid is crucial, especially for knocked-out teeth (avulsion), and involves controlling bleeding, managing pain, and proper handling/storage of the tooth.

-

- Prompt professional dental care is essential for accurate diagnosis (including X-rays and vitality tests) and appropriate treatment.

-

- Treatment varies widely, from simple bonding and splinting to root canals or extraction.

-

- Healing time is highly variable, depending on the injury type and severity; soft tissues heal fastest, while ligaments and nerve recovery take longer (weeks to months).

-

- Traumatized teeth face risks of delayed complications like nerve death, infection, root resorption, or fusion to bone, necessitating long-term monitoring.

- Many dental injuries are preventable, primarily through the use of mouthguards in sports.

What is Dental Trauma: Understanding Tooth and Mouth Injuries?

Let’s cut to the chase: dental trauma, tooth trauma, mouth trauma, dental injury – these aren’t just different phrases for dentists to sound fancy. They are, for all practical purposes in this context, describing the same fundamental issue: damage to the structures within your mouth, specifically your teeth and the supporting tissues around them. This isn’t your run-of-the-mill cavity or gum disease; this is damage caused by external force, an unexpected impact that disrupts the normal, stable state of your oral anatomy. The scope of what falls under this umbrella term is vast and varied. On one end of the spectrum, you might have a barely perceptible craze line on the enamel – a tiny crack that doesn’t go deep. On the other, you could face a tooth knocked completely out of its socket, extensive fractures, or damage to the jawbone itself. It’s this sheer range of potential injuries, from the superficial to the severe, that makes the category of dental trauma so important to understand. It’s a dynamic field, requiring not just repair of visible damage, but often complex assessment of underlying structures like the tooth’s nerve and the bone surrounding the roots. Critically, the speed at which these injuries are assessed and treated is paramount. A delay of even minutes, particularly in cases like a knocked-out tooth, can dramatically impact the long-term prognosis and the likelihood of saving the affected tooth. So, while the event itself is sudden and unwelcome, your response needs to be swift and informed.

What is dental trauma?

At its core, dental trauma is simply an injury to the teeth or the structures that support them within the mouth. Think of your teeth as anchored firmly in place, cushioned by ligaments, surrounded by gum tissue, and embedded in the sturdy bone of your jaw. When an external force – a punch, a fall, a collision, even biting down on something unexpectedly hard – impacts this delicate system, the resulting damage is classified as dental trauma. The terms “tooth trauma,” “trauma to tooth,” “mouth trauma,” and “dental injury” are essentially interchangeable synonyms used to describe this type of event. They all point to damage incurred through physical force rather than disease processes like decay. This damage can manifest in countless ways, each with its own clinical name and implications. It might be as simple as a chip off the outer enamel layer, or as complex as a tooth being pushed inward (intrusion), pushed outward (extrusion), shifted sideways (luxation), fractured vertically through the root, or even completely dislodged from its socket (avulsion). It can also involve damage to the surrounding gums, the bone supporting the teeth, or the delicate ligaments holding the tooth in place. The severity varies wildly depending on the force of the impact, the direction it came from, and what structures were hit. A minor bump might cause temporary pain, while a significant blow could lead to nerve damage, root fractures, or the loss of multiple teeth. Because of this potential for a wide range of severities and complexities, classifying and understanding the specific type of dental trauma is the first crucial step in determining the appropriate course of action and predicting the potential outcome.

What causes dental trauma?

Dental trauma doesn’t just happen; it’s the result of a physical force acting upon your mouth. And honestly, the ways this can occur are as varied as life itself. We’re talking about those sudden, often unexpected moments that nobody plans for but seem to happen to everyone at some point. The most common culprits? Falls. Kids fall off bikes, adults trip down stairs, everyone seems to occasionally misjudge a step. Sports injuries are massive contributors – think flying pucks, errant elbows, hard landings, or face-first collisions in activities like basketball, soccer, or cycling. Accidents, whether car-related (even with airbags, facial impact can occur) or work-related, also frequently lead to significant dental injuries. Then there are those less pleasant causes like fights or altercations, where direct blows to the face are involved. It’s not always high-impact drama, though. Sometimes it’s something as simple as biting into something exceptionally hard – a stray olive pit, a frozen candy, a piece of bone – that can cause a painful crack or fracture, especially in teeth that might already be weakened. Different types of forces cause different injuries. A direct, sharp impact might fracture a tooth, while a sideways blow could dislodge it from its socket. A force pushing the tooth directly inward can intrude it into the bone, potentially crushing the delicate nerve and blood vessels at the root tip. Understanding the mechanism of the injury – how the trauma occurred – is a vital piece of information for the dentist, as it helps them anticipate the types of damage they might find and the potential complications that could arise, guiding their diagnostic and treatment approach from the outset.

What are the symptoms of dental trauma?

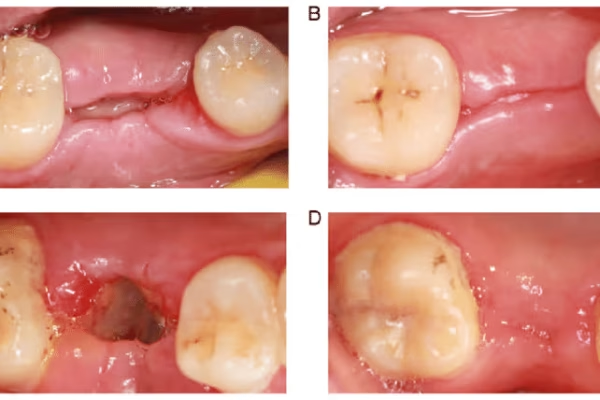

The aftermath of dental trauma can present a confusing mix of symptoms, ranging from immediately obvious visual cues to subtle, nagging sensations that develop over time. Recognizing these signs is crucial for knowing when and how urgently to seek professional help. Visually, you might notice teeth that are chipped, cracked, or outright broken – perhaps even missing entirely. A tooth might look displaced, either pushed inwards towards the tongue, outwards towards the lip, or even sunk down into the gum line (intrusion). Swelling and bruising of the gums, lips, or face are common, indicating damage to the soft tissues and underlying structures. Bleeding, either from the gums around the injured tooth or from lacerations inside the mouth, is also a frequent symptom. Beyond what you can see, there’s a whole host of subjective symptoms. Pain is almost universally present, though its intensity and nature can vary wildly depending on the injury. It might be a sharp, immediate pain, a dull ache, or throbbing discomfort. Sensitivity is another major sign – hot and cold stimuli, or even air hitting the tooth, can trigger intense discomfort, often indicating potential damage to the tooth’s nerve. An inability to bite down comfortably or problems closing your jaw can signal displaced teeth or even jaw fractures. A tooth might feel loose when you touch it with your tongue or finger. Sometimes, a tooth might change colour over time, becoming grey, dark, or pink, which can be a sign of internal bleeding or nerve death. It’s vital to remember that symptoms aren’t always immediately apparent, especially with less severe injuries like concussions (where the tooth is just bruised). Even if things look okay and initially feel fine, internal damage to the nerve or supporting ligaments might only become evident days, weeks, or even months later through pain, discoloration, or signs of infection on an X-ray. This is why professional assessment is always recommended after any notable blow to the mouth, regardless of initial symptoms.

How do you know if your teeth are traumatized?

So, you’ve taken a hit to the mouth – perhaps a minor bump, perhaps something more significant. How do you actually figure out if your teeth are okay or if they’ve joined the traumatized club? First rule: stay calm as best you can. Then, it’s time for a careful self-assessment, keeping in mind that this is not a substitute for seeing a dentist. Start by looking. Get to a mirror with good light. Check all your teeth, especially the front ones which are most vulnerable. Do you see any chips, cracks, or missing pieces? Are any teeth crooked, pushed in, or sticking out further than usual? Compare the injured side to the other side if possible. Look at your gums around the teeth involved. Are they bleeding, swollen, or torn? Now, gently touch each tooth with your finger or tongue. Do any feel loose or wobbly? Try gently tapping on the teeth – is there a sharp pain in any particular one? Very carefully try biting down – does it hurt? Does it feel like your bite is off? Are any teeth suddenly sensitive to temperature? Remember that color changes, like a tooth starting to look grey or dark, are often a delayed sign of trauma, potentially indicating nerve damage that happened days or even weeks ago. Even if you don’t see anything obviously broken or displaced, and the pain seems manageable, a blow strong enough to make you worry warrants a check-up. The dentist has diagnostic tools, like X-rays and vitality tests, that can uncover hidden damage you can’t see or feel yourself, particularly to the tooth’s root, the bone, or the nerve. Trust your gut – if it feels wrong, get it checked. It’s always better to be safe than sorry when it comes to potential nerve damage or root issues that could silently progress and threaten the tooth’s long-term survival.

What is the most common dental trauma?

When we talk about dental trauma, while the severe stuff like knocked-out teeth grabs headlines (and requires immediate, dramatic action), the reality is that the most frequent injuries tend to be less catastrophic but still significant. The undisputed champion of common dental trauma is the enamel fracture. This is essentially a chip or crack in the outer layer of the tooth, the hard enamel, that doesn’t extend into the deeper dentin or the tooth’s nerve (pulp). It might look small, but even minor enamel damage can create sharp edges that irritate your tongue or lip, and depending on location, it can significantly impact the tooth’s appearance. While often not an emergency requiring immediate treatment beyond smoothing the sharp edge, these fractures still need dental assessment to ensure they haven’t extended further than visible and to determine the best way to restore the tooth aesthetically and functionally, often with simple bonding. Following closely in frequency are luxation injuries. This is where the tooth isn’t knocked out, but it’s been moved within its socket. There are different types: concussions (the tooth is bruised but not moved), subluxations (the tooth is loose but not displaced), extrusions (partially out of the socket), lateral luxations (pushed sideways), and intrusions (pushed into the gum/bone). Subluxations and concussions are quite common, often resulting from minor bumps or falls. The tooth might feel tender or slightly loose, but isn’t visibly out of place. While seemingly minor, luxation injuries carry a significant risk of damage to the tooth’s nerve and the periodontal ligaments, often requiring root canal treatment or potentially leading to root resorption down the line, even if the tooth initially survives. So, while major breaks and avulsions happen, superficial fractures and teeth that are merely loosened or bruised are the everyday reality of dental trauma across the population, highlighting the need for vigilance and professional check-ups even after seemingly small incidents.

What is the first aid for dental trauma?

Okay, the unthinkable has happened: you or someone nearby has suffered a dental injury. Panic might be the first response, but seconds count. Knowing immediate first aid for dental trauma is absolutely critical and can dramatically improve the outcome, potentially saving a tooth that might otherwise be lost. Your primary goals in the immediate aftermath are threefold: controlling any bleeding, managing the pain as best as possible, and crucially, handling any displaced or knocked-out tooth parts correctly to give them the best chance of survival if replantation is an option. The scene might be messy – blood, potentially fractured tooth pieces, maybe a visibly displaced tooth. Take a deep breath. If there’s bleeding, apply gentle but firm pressure to the injured area using a clean cloth or gauze. This helps staunch the flow. Pain relief can be managed with over-the-counter pain medication like ibuprofen (which also helps with swelling) or acetaminophen, provided the person can swallow safely. Cold compresses applied to the outside of the face near the injury can help reduce swelling and numb the area, providing some comfort. The absolute most time-sensitive scenario is an avulsed tooth – one that has been completely knocked out of its socket. If this happens, locating the tooth immediately is paramount. Handle it only by the crown (the white part), avoiding touching the root. If it’s dirty, rinse it gently with cold water for no more than 10 seconds – don’t scrub it or use soap! The goal is to get it back into the socket as quickly as possible. If you can’t replant it immediately, store it in a suitable medium. The best options are typically a special tooth-preserving solution (if available in a first aid kit), cold milk, or saline solution. Water is the least preferred option as it can damage the root surface cells. Get to a dentist or emergency room immediately with the tooth stored correctly. For fractured teeth, try to find any broken pieces. Keep them, as sometimes they can be bonded back onto the tooth. Rinse the mouth gently with warm water to clean it and remove any debris. Regardless of the type of injury, the most important first aid step after the initial calming and stabilization is to seek professional dental care as soon as humanly possible. Don’t delay – the sooner a dentist sees the injury, the better the prognosis usually is.

Dental injury first aid steps explained

Let’s break down the crucial steps you need to take if a dental injury occurs, making it actionable and easy to follow during a stressful moment. First and foremost, if it’s a severe injury involving significant bleeding, loss of consciousness, or potential jaw fracture, your first stop might be a hospital emergency room, not just a dentist’s office. However, for most isolated tooth/mouth injuries, a dental emergency visit is the priority. Here’s what you do:

-

- Stay Calm (as much as possible): Assess the situation. Is there significant bleeding? Are teeth chipped, loose, or missing?

-

- Control Bleeding: Apply firm pressure directly to the injured area using clean gauze, a clean cloth, or even a tea bag (tannins can help with clotting). Keep pressure on for several minutes.

-

- Manage Pain & Swelling: Have the injured person gently rinse their mouth with warm salt water if possible (this helps clean and soothe). An over-the-counter pain reliever like ibuprofen (if appropriate) can help with pain and inflammation. Apply a cold pack or ice wrapped in a cloth to the outside of the cheek or lip near the injury – 10-20 minutes on, 10-20 minutes off.

-

- Handle Specific Injuries:

-

-

- Chipped/Fractured Tooth: Find the piece(s)! Keep them in a small container with milk or saline. Rinse the mouth gently with water. Avoid biting on the tooth.

-

-

-

- Loose/Displaced Tooth: Do not try to force it back into place yourself. Avoid touching it or biting on it. Keep the area clean with gentle rinsing.

-

-

-

- Knocked-Out Tooth (Avulsion): This is the biggest emergency. FIND THE TOOTH! Handle it only by the crown (the chewing surface). Do NOT touch the root. If it’s dirty, rinse gently under cold running water for maximum 10 seconds; do not scrub or dry it. The absolute best scenario is to gently try and place it back into its socket yourself if the person is conscious and cooperative. Push it gently into position and have them hold it there by biting down on gauze or a clean cloth until you reach the dentist. If immediate replantation isn’t possible, store the tooth in one of these mediums: special tooth preservation media (like Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution), cold milk, or saline solution. Last resort is placing it between the cheek and gums in the mouth (but this carries aspiration risk, especially for children). Get to the dentist immediately – within 30-60 minutes is ideal for the best prognosis.

-

-

-

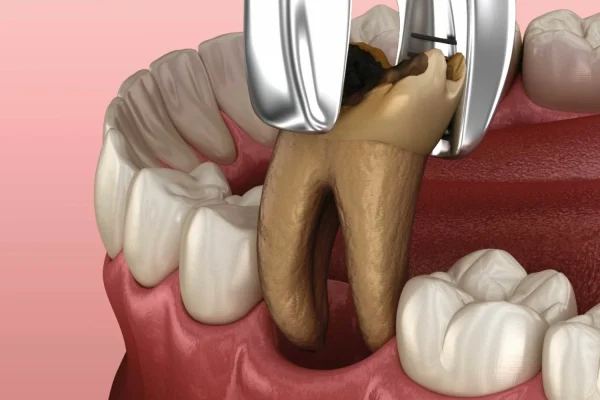

- Tooth Extraction: In cases of severe trauma, a tooth may be irreparable and require removal.

-

- Seek Immediate Dental Care: Call your dentist or an emergency dental service right away. Explain the injury and that you need to be seen urgently. Time is of the essence for many dental traumas. Even if the injury seems minor, a professional assessment is crucial to check for hidden damage.

Following these steps can significantly impact the tooth’s future health and survival chances. Be prepared, act swiftly, and always prioritize getting professional help.

How are dental injuries diagnosed?

So, you’ve taken the initial first aid steps and arrived at the dentist’s office or emergency clinic. What happens now? The diagnosis of dental injuries isn’t just a quick glance; it’s a thorough process that combines gathering information about the incident with a detailed clinical examination and specific diagnostic tests. The dentist’s goal is to determine exactly which structures are injured, the severity of the damage, and whether the tooth’s vital components, like the nerve and blood vessels, are still alive and healthy. It starts with a crucial step: taking a comprehensive history of the injury. The dentist will ask how it happened – the type of force, the direction of impact, where you were hit, and importantly, when it happened. They’ll also want to know about your immediate symptoms and any first aid steps you took. This information helps them anticipate potential injury patterns. Next comes the clinical examination. The dentist will visually inspect your face, lips, gums, and teeth for any signs of swelling, bruising, lacerations, bleeding, or visible tooth damage (chips, cracks, displacement). They’ll gently feel (palpate) the bone around the teeth and jaw to check for tenderness or signs of fracture. They’ll check for tooth looseness by gently trying to wiggle each tooth. They might tap lightly on the teeth to assess for pain or unusual sounds, and they’ll check your bite to see if any teeth are interfering or if your jaw alignment feels off. This systematic approach allows the dentist to build a clear picture of the injury’s extent before moving on to internal assessments using diagnostic tools. It’s a combination of detective work and clinical expertise aimed at uncovering the full story of the trauma, much of which lies hidden beneath the surface.

Diagnosis and Tests Used for Dental Trauma

Once the dentist has the history and has conducted a visual examination, they’ll turn to specific diagnostic tools to confirm their suspicions and uncover any hidden damage. Dental X-rays are indispensable in diagnosing dental trauma. Standard periapical X-rays provide detailed images of the entire tooth, from crown to root tip, as well as the surrounding bone. These are critical for checking for root fractures (which often aren’t visible clinically), assessing the position of displaced teeth within the bone, looking for damage to the bone socket, and checking for any signs of infection or inflammation around the root. Sometimes, multiple X-rays from different angles are needed to get a clear picture, especially if a fracture is suspected. For more complex cases, particularly those involving potential jaw fractures, extensive bone damage, or intricate displacement, Cone-beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) might be used. This advanced imaging technique provides a 3D view of the teeth, bone, and surrounding anatomy, offering much greater detail than standard 2D X-rays and making it easier to visualize complex fractures or the exact position of an intruded tooth. Beyond imaging, pulp vitality tests are essential. These tests assess the health and responsiveness of the tooth’s nerve (pulp). Common methods include thermal tests (applying something cold or hot to the tooth surface and noting the response) and electric pulp tests (delivering a small electric current to see if the nerve reacts). A healthy nerve responds quickly to cold and the sensation fades rapidly. A damaged nerve might have an exaggerated, prolonged, or absent response. It’s important to know that immediately after trauma, the nerve can be in shock and might not respond even if it’s still viable; therefore, vitality tests are often repeated at follow-up appointments to monitor the nerve’s recovery over time. The combination of the patient’s history, clinical examination findings, X-ray images, and vitality test results allows the dentist to arrive at an accurate diagnosis and formulate the most appropriate treatment plan for the specific type and severity of dental trauma.

Vitality Tests for Pulp Diagnosis of Traumatized Teeth Explained

Let’s zero in on those vitality tests – they might sound a bit sci-fi, but they are absolute workhorses in assessing the impact of trauma on the tooth’s most vulnerable part: the pulp, or the nerve. The pulp is a bundle of nerves, blood vessels, and connective tissue housed within the tooth’s core. Trauma, especially luxation injuries (where the tooth is moved) or fractures extending deep into the tooth, can disrupt the blood supply or directly damage these delicate tissues. Pulp vitality tests don’t actually measure blood flow (that’s done with laser Doppler flowmetry, a less common method), but rather the response of the nerve fibres within the pulp, which is often a good indicator of whether the pulp is alive and reasonably healthy. The two most common types are thermal tests and electric pulp tests (EPT). Thermal tests usually involve applying something cold, like a cotton pellet sprayed with a special refrigerant, to the tooth surface. A healthy tooth with vital pulp will react with a sharp, but quickly fading, sensation. An exaggerated or prolonged pain might suggest inflammation (reversible pulpitis), while no response at all suggests the nerve might be dead (necrosis). Hot tests are also used but less frequently, as they can be harder to isolate to a single tooth. EPT involves placing a small probe on the tooth surface and gradually increasing a low electrical current. A healthy nerve will typically feel a tingling or warm sensation at a certain level of current. Again, no response suggests potential necrosis. Why are these critical after trauma? Because a tooth can look perfectly intact on the outside, or appear slightly loose, but have severe, non-recoverable damage to the nerve due to the force of the impact disrupting the blood supply at the root tip. An early diagnosis of pulp necrosis is crucial because dead pulp tissue can become infected, leading to an abscess and threatening the tooth’s long-term retention and the surrounding bone. However, there’s a caveat: right after trauma, the nerve can be in shock and may give a false negative result (no response even if it’s still alive). This is why dentists never rely on a single test immediately after the injury and why follow-up vitality testing over weeks and months is absolutely essential to monitor the tooth’s true pulpal status and detect potential problems before they escalate.

How is dental trauma treated?

Okay, the diagnosis is in. Now comes the action – treatment. The approach to treating dental trauma is not a one-size-fits-all deal; it’s highly specific and depends almost entirely on the exact nature and severity of the injury, as well as which tooth is affected (permanent vs. primary). The overarching goals of treatment are generally to preserve the tooth structure and vitality whenever possible, restore function so you can chew and bite normally, eliminate pain, prevent infection and long-term complications, and finally, restore aesthetics, especially for front teeth, so you can smile confidently. Think of it as a tailored rehabilitation plan for your injured tooth. A minor chip might just need a quick polish or some aesthetic bonding. A fracture extending into the nerve will likely require a root canal. A loose tooth needs stabilization, while a knocked-out tooth demands immediate replantation and stabilization. Bone fractures might require surgical intervention. The dentist or specialist will walk you through the specific recommended treatment based on their findings from the diagnosis. Sometimes, treatment involves multiple steps over time. An initial visit might focus on stabilizing the tooth and managing immediate pain and risk of infection, followed by procedures weeks or months later to restore the tooth’s appearance or address delayed complications like nerve death or root resorption. The key takeaway is that treatment is individualized and often requires follow-up care to monitor healing and address any issues that arise down the line. Simply patching up the visible damage isn’t enough; successful treatment of dental trauma involves safeguarding the long-term health and stability of the tooth within its socket.

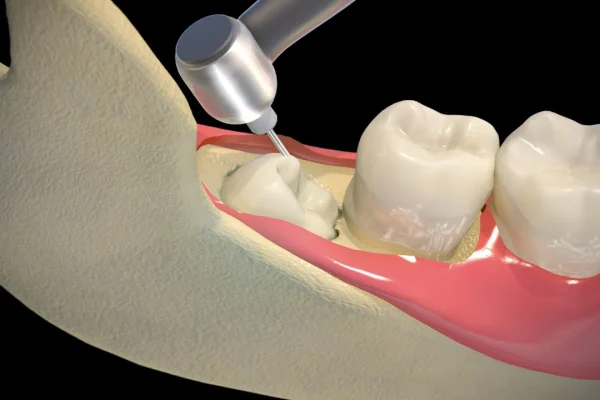

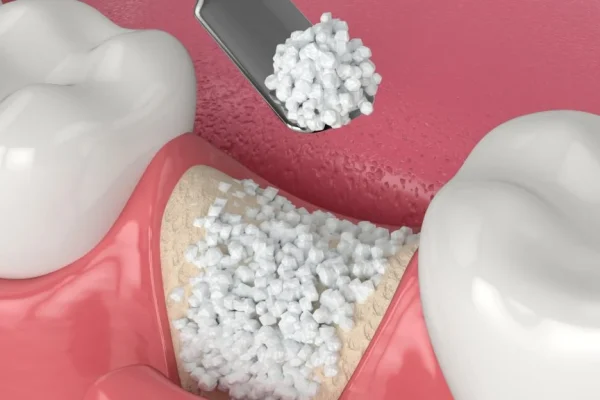

Treatments for Dental Trauma and Mouth Injuries

Treating dental trauma involves a fascinating array of techniques, each chosen to best address the specific damage incurred. For simple chips or minor fractures involving only enamel, the treatment is often straightforward: the sharp edge might be smoothed off, or a tooth-colored composite resin (bonding) can be used to rebuild the missing part, restoring both shape and function quickly and often invisibly. If the fracture extends into the dentin but not the pulp, bonding might still be an option, or a more extensive restoration might be needed depending on the size. If the fracture exposes the tooth’s nerve (pulp), then the treatment usually shifts dramatically towards preserving the tooth while dealing with the now-compromised nerve. This often necessitates root canal treatment, where the damaged or infected pulp is removed, the internal canals cleaned and disinfected, and then filled to prevent future infection. For teeth that are loose or displaced (luxated), the primary treatment is repositioning and splinting. The dentist will gently guide the tooth back into its correct position if it’s been moved. Then, a small, flexible splint (often made of composite resin and wire or nylon fishing line) is bonded to the injured tooth and usually the two teeth on either side, effectively acting like a tiny brace to hold the injured tooth stable while the supporting ligaments heal. The splint is typically kept in place for a few weeks, the exact duration depending on the type of luxation. An avulsed (knocked-out) tooth, if replanted quickly and correctly (as discussed in first aid), will also be splinted to allow the ligaments a chance to reattach. However, replanted teeth almost always require root canal treatment within a couple of weeks because the nerve and blood vessels supplying the pulp are severed during the avulsion event. In cases of severe fracture where the tooth cannot be restored, or if complications arise that threaten surrounding teeth or bone, extraction (removal) might be the only option. Soft tissue injuries like cuts to the gums or lips are cleaned and may require sutures (stitches) to help them heal properly. The specific treatment is a delicate balancing act, weighing the extent of the damage, the potential for healing, and the tooth’s long-term prognosis.

Which type of specialist treats dental trauma?

While your general dentist is often the first point of contact and is capable of managing many common and less complex dental trauma cases, there are situations where the injury requires the expertise of a dental specialist. Think of it like seeing your primary care doctor for a sprained ankle versus needing an orthopedic surgeon for a shattered bone. General dentists are equipped to handle things like minor chips, uncomplicated fractures, assessing loose teeth, providing initial first aid for avulsed teeth, and often placing temporary splints. However, for injuries that delve deeper or involve more intricate structures, they will likely refer you to a specialist. Endodontists are the go-to experts when the tooth’s pulp (nerve) is involved. Since trauma frequently damages the nerve, endodontists specialize in diagnosing and treating issues inside the tooth, particularly performing root canal treatments, which are very common after significant trauma, luxations, or avulsions. Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons are specialists in treating injuries and conditions of the jaw, mouth, and face. They are essential for managing more severe trauma, such as complex tooth fractures extending into the bone, jaw fractures, teeth that are severely intruded into the bone, or complicated extractions if a tooth cannot be saved. Periodontists focus on the supporting structures of the teeth – the gums, bone, and ligaments. While less commonly the primary specialist for trauma, they might be involved if the trauma has caused significant damage to the gum tissue or alveolar bone surrounding the tooth, or if complications like root resorption or bone loss develop later. Orthodontists might even play a role, though usually much later in the process, if a displaced tooth needs to be gently moved back into alignment or if trauma to primary teeth has affected the eruption pattern of permanent teeth. Ultimately, the specific specialist involved depends entirely on the structures affected and the complexity of the treatment needed. Your general dentist will assess the injury and guide you to the appropriate expert if necessary.

How to treat front teeth trauma?

Trauma to the front teeth (incisors and canines) is particularly common, not just because they are at the front line and exposed to impact, but also because they are critical for both function (biting, tearing food) and aesthetics (your smile!). Treating trauma in this highly visible area carries the added weight of ensuring the outcome looks natural and blends seamlessly with the surrounding teeth. The specific treatment for front teeth trauma mirrors that of back teeth but with an increased emphasis on cosmetic results. Minor chips are frequently repaired using tooth-colored composite resin bonding. This material can be sculpted and polished to perfectly match the tooth’s original shape and color, often making the repair virtually invisible. For larger fractures, especially those involving dentin or the pulp, the treatment might range from extensive bonding to veneers or crowns, particularly if the remaining tooth structure is weakened or if significant discoloration occurs later. Crowns cover the entire tooth and can restore its form and function while masking discoloration, but they are a more invasive treatment option. Luxation injuries (loose or displaced teeth) in the front are treated with repositioning and splinting, just like back teeth, but splints on front teeth need to be placed carefully to allow for proper function and hygiene while maintaining stability. Avulsion (a knocked-out front tooth) is one of the most visually dramatic and urgent types of trauma, and prompt replantation (ideally within 30-60 minutes) is critical for survival. If successful, the tooth will be splinted, and root canal treatment will almost certainly be needed within a couple of weeks. Discoloration, particularly the tooth turning grey, is a common consequence of nerve damage in front teeth. If root canal treatment is needed for a discolored tooth, internal bleaching (bleaching applied inside the tooth) or external whitening followed by a veneer or crown may be used to restore the natural color. Because of the aesthetic stakes, treating front teeth trauma often requires not only clinical skill but also an artistic touch to ensure the repaired tooth looks as good as the original.

How to fix a loose tooth from trauma?

Finding yourself with a loose tooth after a knock to the mouth can be incredibly unsettling. It wiggles when you touch it, maybe hurts when you try to bite, and feels alarmingly unstable. The primary way dentists “fix” or stabilize a loose tooth caused by trauma (a luxation injury) is through a process called splinting. Think of a splint as a tiny, temporary brace for your tooth. The purpose of splinting is to hold the injured tooth firmly in its correct position within the socket while the damaged periodontal ligaments – the tiny fibers that anchor the tooth root to the surrounding bone – have a chance to heal and reattach. You should absolutely not try to tighten a loose tooth yourself at home with wires, glues, or any other improvised method; this can cause more harm than good and potentially introduce infection. Instead, see a dentist as soon as possible. The dentist will first assess the severity of the looseness and check for other damage like root fractures or nerve injury using X-rays and vitality tests. If splinting is appropriate, they will gently reposition the tooth if it’s been displaced. Then, they will apply a dental splint, which typically consists of a thin wire or fiber (like nylon fishing line) that is bonded using composite resin (tooth-colored filling material) across the injured tooth and usually one or two stable, uninjured teeth on either side. This creates a rigid or semi-rigid framework that keeps the loose tooth from moving while the ligaments recover. The duration of splinting varies depending on the type of luxation, but it’s typically kept in place for a few weeks (e.g., around 2 weeks for a subluxation, 2-4 weeks for a more severe luxation). During this time, it’s crucial to maintain excellent oral hygiene around the splint and eat a soft diet to avoid putting stress on the healing tooth. After the prescribed time, the dentist will gently remove the splint and check the tooth’s stability. Importantly, even after splinting, the injured tooth needs to be monitored long-term for signs of nerve damage or root resorption, as these can be delayed complications of luxation injuries.

Can a dentist push a tooth back into place?

Yes, absolutely! Pushing a tooth back into place is a critical emergency procedure performed by dentists for specific types of dental trauma, namely luxation injuries where the tooth has been displaced, and especially for avulsion injuries, where the tooth has been completely knocked out of its socket. When a tooth is pushed inwards (intruded), outwards (extruded), or sideways (laterally luxated), the dentist’s first step after diagnosis is often to gently, but firmly, guide or push the tooth back into its correct anatomical position within the alveolar bone socket. This procedure is called reduction or repositioning. It’s done under local anesthetic to minimize discomfort. The goal is to restore the tooth’s natural alignment and seating within the socket, which is essential before it can be stabilized. For a tooth that has been completely knocked out (avulsed), the process involves replantation. If the tooth has been preserved correctly since the injury and the patient presents quickly enough (ideally within that critical first hour), the dentist will clean the socket and the tooth root (if necessary, very gently), and then carefully insert the tooth back into its original socket. Pushing the tooth back into place – whether repositioning a luxated tooth or replanting an avulsed one – is not the end of the treatment. It’s just the beginning. Once the tooth is back in its intended position, it must be stabilized with a dental splinting bonded to adjacent healthy teeth, as discussed previously. This splint holds the tooth firmly while the supporting structures (ligaments and potentially bone) heal. The success of both repositioning and replantation heavily depends on the promptness of care, the skill of the dentist, and the specific nature of the injury and how the tooth was handled beforehand. While the dentist can definitely push a tooth back, this is a procedure that requires immediate professional expertise and follow-up care.

How Long Does it Take for Tooth Trauma to Heal?

This is the million-dollar question for anyone who’s suffered a dental injury, and frustratingly, there’s no single, simple answer. The healing timeline for dental trauma is highly variable and depends on a multitude of factors: the specific type of injury, its severity, whether it’s a primary (baby) or permanent tooth, the promptness and effectiveness of treatment, and even the individual’s own healing capacity and overall health. Healing from dental trauma isn’t just about visible improvements; it involves complex biological processes happening at the root level, within the bone, the ligaments, and the tooth’s pulp. A minor chip might heal in the sense that the discomfort fades quickly after smoothing or bonding, with the tooth structurally restored within a single appointment. A subluxation (loose tooth without displacement) might feel stable again within a couple of weeks after splint removal, but the underlying ligament healing continues for weeks to months. A tooth that has been severely luxated or avulsed (knocked out) represents the most complex healing scenario. While the tooth is splinted for a relatively short period (typically 2-4 weeks), the true healing of the periodontal ligaments is a lengthy process that can take several months. Even then, replanted teeth or those with severe luxations often face long-term risks like root resorption or ankylosis (fusing to the bone), which can develop years later and ultimately lead to tooth loss. Healing also involves the tooth’s nerve; if it was damaged but potentially salvageable, vitality might return over weeks or even months, or it might never recover, eventually leading to necrosis. Because of this complexity and the potential for delayed complications, successful management of dental trauma requires ongoing monitoring by a dentist for months or even years after the initial injury. There’s the initial healing phase focused on stabilization and immediate recovery, and then a long-term monitoring phase to ensure the tooth remains healthy and vital.

Can damaged teeth recover?

The answer to whether damaged teeth can recover is a nuanced “sometimes, depending on the damage.” Unlike skin or bone, the hard structure of a tooth (enamel, dentin, cementum) cannot regenerate or “grow back” if it’s been lost or fractured. A chipped piece of enamel or a fractured section of dentin is gone forever unless it’s artificially replaced or repaired by a dentist through bonding, fillings, veneers, or crowns. The tooth structure itself doesn’t spontaneously heal or regenerate. However, other components involved in dental trauma can recover or heal to some extent. The periodontal ligaments, which connect the tooth to the bone, are capable of healing after injuries like luxation or avulsion, provided the tooth is stabilized. Gum tissue also has excellent healing capacity; lacerations typically heal within a couple of weeks. The tooth’s nerve (pulp) has a limited capacity for healing. If the trauma caused only a mild inflammation or concussion without severely disrupting the blood supply, the pulp might recover over time, regaining normal sensation and vitality. This is sometimes referred to as reversible pulpitis resolving. But if the trauma is severe – causing pulp exposure, severing blood vessels (as in avulsion), or compressing them significantly (as in intrusion) – the pulp often suffers irreversible damage (irreversible pulpitis or necrosis) and cannot heal on its own; it will require root canal treatment to save the tooth from infection. So, while the hard structure of the tooth itself doesn’t recover or regenerate, the surrounding supporting tissues and, in some cases, the tooth’s internal pulp can undergo healing processes. The goal of dental treatment after trauma is often to facilitate the healing of these soft tissues and, if the pulp is irreversibly damaged, to intervene to prevent infection and preserve the tooth’s function and structure through procedures like root canals and restorations, essentially helping the tooth “recover” its ability to remain in the mouth and function without pain or infection, even if its internal biology has changed.

Can a tooth survive trauma?

Yes, absolutely. Many teeth survive traumatic injuries, often with appropriate and timely dental intervention. The “survival” of a tooth after trauma refers to its ability to remain functional, pain-free, and healthy within the mouth for the long term. However, whether a tooth survives and thrives depends on a complex interplay of factors. The type of injury is hugely significant. A minor enamel chip is highly unlikely to threaten tooth survival, while a root fracture or a severe intrusion injury (tooth pushed into the bone) has a much guarded prognosis. The severity of the injury also plays a major role – a slightly loose tooth has a better chance than one that is completely avulsed (knocked out), although even avulsed teeth can be saved if replanted quickly and correctly. Promptness of treatment is critical, especially for avulsed teeth where every minute counts in preserving the viability of the root surface cells necessary for reattachment. The quality and appropriateness of the dental treatment received also heavily influences survival; correct repositioning, stabilization with a proper splint, and timely root canal treatment (if needed) are essential steps. The success of the biological healing processes, such as the repair of the periodontal ligaments and the survival or successful treatment of the pulp, is also paramount. Lastly, the individual’s body’s response and the absence of complications like infection, severe root resorption, or ankylosis (fusion to bone) are crucial for long-term survival. While a tooth’s hard structure can’t heal itself, modern dentistry, combined with the body’s capacity for healing surrounding tissues, offers excellent possibilities for saving teeth that would have been lost in the past. However, “surviving” trauma often means requiring ongoing monitoring and potentially future interventions over the tooth’s lifetime due to the initial injury. It’s less about spontaneous recovery and more about successful management and the avoidance of detrimental complications that could lead to its eventual loss.

Can dental trauma heal on its own?

This is a question that often leads people to delay seeking help, and it’s crucial to address directly: severe dental trauma generally does not heal fully or correctly on its own without professional intervention. While your body is an amazing healing machine, a tooth isn’t like a cut on your skin or a broken bone that can knit back together perfectly with just rest and time (and sometimes a cast). Minor injuries like a tooth concussion (just bruised, no visible movement or fracture) might see the pain and sensitivity gradually fade over time as the inflammation settles, but even these should be checked by a dentist to rule out hidden nerve damage or root issues that might only become apparent later. A tiny craze line (surface crack) might remain stable without treatment. However, for anything more significant – a chip involving dentin, any type of looseness or displacement, a visible fracture, or a knocked-out tooth – professional dental care is absolutely essential. Leaving these injuries untreated carries significant risks. A fractured tooth left open to the mouth environment can lead to infection of the pulp, causing severe pain and potentially spreading to the surrounding bone (abscess). A loose tooth that isn’t splinted correctly might not heal properly, leading to ongoing instability, pain, or eventual loss. A knocked-out tooth must be replanted and splinted quickly to have any chance of survival, and even then it typically requires root canal treatment soon after because the nerve is severed. Untreated or improperly treated trauma can lead to a cascade of long-term complications, including chronic pain, infection, root resorption (where the body dissolves the tooth root), fusion of the tooth to the bone (ankylosis), discoloration, and ultimately, the loss of the tooth. So, while some very minor symptoms might subside temporarily, the underlying damage from anything beyond a superficial bruise or surface line requires professional assessment and often treatment to prevent serious, irreversible problems down the road. Waiting for it to just “heal itself” is a gamble with very poor odds when it comes to dental trauma.

How long will teeth hurt after trauma?

The duration of pain and sensitivity after dental trauma is highly variable and depends on the specific injury, the structures involved, and the treatment received. Immediately after the injury, acute pain is common due to impact on the tooth, surrounding tissues, and potentially exposed nerve endings. This initial pain can range from mild to excruciating. With proper first aid (like cold compresses and over-the-counter pain relievers) and prompt professional treatment, this acute pain typically starts to subside within a few days to a week. However, it’s common to experience lingering discomfort or sensitivity for much longer. Teeth that have suffered luxation injuries (loosening or displacement) or even just concussions often remain sensitive to biting pressure or temperature changes for several weeks, sometimes even a couple of months, as the periodontal ligaments and potentially the nerve are healing or recovering from shock. If a root canal was performed because the nerve was irreversibly damaged, the tooth itself will no longer feel temperature sensitivity (as the nerve tissue has been removed), but there might be discomfort from the surrounding tissues healing, which usually resolves within a week or two after the procedure. If pain persists or worsens after the initial treatment phase, or if new symptoms like swelling or a bad taste develop, it’s a major red flag that a complication might be developing, such as infection (an abscess) or ongoing nerve issues, and you should contact your dentist immediately. Likewise, if a tooth that was initially sensitive suddenly stops hurting completely, but starts to change colour (like turning grey), this can indicate nerve death, which is painless but requires treatment (root canal) to prevent future infection. So, while initial acute pain should lessen within days of treatment, some degree of sensitivity or discomfort can linger for weeks to months as healing progresses, but persistent or increasing pain warrants immediate re-evaluation by your dentist.

Is tooth damage reversible?

When we talk about “reversing” tooth damage, it’s important to be precise. Can the physical loss of tooth structure – a chip or a fracture – be reversed? No, not in the sense that the tooth material grows back. Once enamel, dentin, or cementum is lost, it’s gone forever. However, the consequences of that damage, or the function of the tooth, can often be restored or reversed through dental treatment. For example, a chipped tooth can be repaired with bonding or a veneer, effectively reversing the aesthetic and functional deficit even though the original piece isn’t back. Nerve inflammation caused by trauma might be reversible if the injury was mild (reversible pulpitis); in these cases, the nerve function can recover on its own, and the tooth’s normal sensation returns. This is a form of biological reversal of the pulp’s reaction to trauma. But if the nerve damage is severe and irreversible (necrosis), the biological process cannot be reversed. However, the negative outcome of nerve death (infection, pain, abscess) can be prevented and managed through root canal treatment, allowing the tooth to remain healthy and functional, which you could argue is a form of clinical reversal of the potential negative spiral. Similarly, a loose tooth (luxation) isn’t physically “undamaged,” but splinting allows the damaged ligaments to heal and reattach, effectively reversing the instability caused by the trauma. Root resorption, a serious complication where the body breaks down the root, is generally not reversible once it starts progressing, although certain types can be managed if caught early, and treatment like root canal therapy is critical in trying to halt inflammatory resorption. So, think of it less as physical reversal of the tooth structure itself (which doesn’t happen) and more as clinical reversal or successful management of the effects and complications of trauma, allowing the tooth to function normally and remain healthy for as long as possible. Prompt and appropriate treatment is key to achieving the maximum possible degree of “reversal” of the trauma’s negative impacts.

What can I expect if I have dental trauma?

Experiencing dental trauma is a stressful event, and knowing what to expect can help manage the process. Here’s a general roadmap of what you’re likely to encounter, from the moment of impact through recovery:

-

- Immediate Aftermath: Expect pain, potential bleeding, and potentially visible damage like chips, looseness, or displacement. Panic is a common initial reaction.

-

- First Aid: You or someone else will need to take immediate steps: control bleeding, manage pain (cold pack), handle any knocked-out pieces correctly (store in milk/saline/media), and clean the area gently.

-

- Urgent Dental Visit: This is crucial. You’ll need to get to a dentist or emergency clinic as soon as possible, ideally within hours for many injuries, particularly avulsion.

-

- Diagnosis: The dentist will take a history of the injury, perform a thorough clinical examination (looking, feeling, checking looseness), and take X-rays. They may also do vitality tests to check the nerve.

-

- Treatment Planning: Based on the diagnosis, the dentist will explain the specific injury and propose a treatment plan tailored to your situation. This could range from simple bonding to splinting, root canal therapy, or even extraction.

-

- Treatment Procedure: The planned treatment will be carried out. This might happen immediately for emergencies like replantation or splinting, or it might be scheduled for a follow-up visit for restorations or root canals. Local anesthetic will typically be used to ensure comfort.

-

- Post-Treatment & Recovery: Expect some residual soreness or sensitivity after treatment. You’ll likely be advised on pain management, oral hygiene instructions (gentle brushing, possibly specific rinses), and dietary restrictions (soft foods, avoid biting on the injured tooth/area). If you have a splint, you’ll need to be extra careful cleaning around it.

-

- Follow-up Appointments: These are absolutely critical! Dental trauma recovery isn’t usually a one-and-done visit. You’ll need follow-up appointments to check the tooth’s healing, monitor vitality tests (especially for luxated teeth), remove splints, and check for developing complications like infection or root resorption. These follow-ups might be scheduled for weeks, months, and potentially even years after the initial injury.

-

- Potential Complications: Be aware that despite the best treatment, complications like nerve death (requiring root canal), discoloration, root resorption, or ankylosis can still occur, sometimes months or years later. This is why long-term monitoring is so important.

- Long-Term Outlook: With successful treatment and no complications, the injured tooth can often remain healthy and functional for many years. However, some traumatized teeth may require future treatments or ultimately be lost, depending on the initial damage and subsequent events.

Navigating dental trauma requires patience, diligence with follow-up care, and clear communication with your dental team. It’s a journey from acute injury to long-term stability.

Healing Specific Tissues After Dental Trauma

While the tooth structure itself doesn’t regrow, the parts that support and connect the tooth to your jaw – the ligaments, gums, and the tooth’s internal nerve tissue – are living tissues capable of varying degrees of healing after trauma. Understanding how these specific tissues recover is key to appreciating the complexity of dental trauma management and the importance of follow-up care. The periodontal ligaments, those tiny fibers that suspend the tooth in its socket, are often stretched, torn, or crushed during luxation or avulsion injuries. Their healing is essential for the tooth to become firm and stable again. Gum tissue (gingiva) can be lacerated or bruised during impact; this soft tissue generally heals quite well due to its good blood supply, but larger tears may require sutures. The tooth’s nerve (pulp) is perhaps the most vulnerable component to traumatic injury, especially if the blood vessels at the root tip are damaged. Its ability to heal or survive dictates whether the tooth remains ‘alive’ or requires root canal therapy. Each of these tissues has a different healing capacity and timeline, and damage to one can impact the recovery of another, making the overall healing process for a traumatized tooth a dynamic and sometimes unpredictable affair that requires careful monitoring by a dental professional.

Can a traumatized tooth nerve heal?

The tooth nerve, or dental pulp, is a sensitive bundle of nerves and blood vessels residing in the core of your tooth. Its ability to heal after trauma depends heavily on the type and severity of the injury. If the trauma is minor – perhaps just a slight concussion or a fracture that doesn’t expose the pulp but causes some inflammation – the nerve tissue might experience a temporary shock or reversible inflammation (known as reversible pulpitis). In these cases, the inflammation can subside over time, and the nerve can heal, regaining its normal function and responsiveness to stimuli. This healing process can take weeks to months, and its success is monitored through follow-up vitality tests. However, more severe trauma often causes irreversible damage to the pulp. Fractures that expose the pulp to the bacteria in the mouth environment, or luxation injuries (like intrusion or avulsion) that sever or severely compromise the blood supply to the pulp at the root tip, typically lead to irreversible pulpitis or complete pulp necrosis (nerve death). Once the pulp tissue has died, it cannot heal or regenerate. The dead tissue becomes a potential breeding ground for bacteria, which can lead to infection spreading from the tooth into the jawbone, causing an abscess. In these cases, the only way to save the tooth from infection and eventual loss is to remove the dead or dying pulp tissue through root canal treatment. So, while a mildly traumatized nerve can sometimes heal, severe trauma almost always leads to irreversible damage requiring intervention, not spontaneous recovery.

How long does nerve damage take to heal dental?

The healing timeline for a dental nerve after trauma is highly variable and depends entirely on whether the damage is reversible or irreversible. If the nerve damage is reversible (e.g., mild inflammation from a concussion or minor fracture), healing can occur over a period of weeks to months. Initially, the nerve might be in shock and not respond to vitality tests. Over the subsequent weeks and months, if the inflammation resolves and the blood supply wasn’t permanently disrupted, the nerve fibres can recover, and the tooth will start responding normally to cold or electric pulp tests again. This recovery is typically monitored by the dentist with follow-up vitality tests at intervals (e.g., 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, 1 year post-injury). You might notice a gradual decrease in sensitivity or discomfort during this time. However, if the nerve damage is irreversible (necrosis), the nerve tissue will not heal. Instead, it dies, and this process can take anywhere from a few days to several weeks after the initial injury. Once the nerve is necrotic, it remains that way; there is no biological healing. The concern then shifts to preventing infection from developing within the dead pulp tissue. If nerve death is diagnosed (often through non-responsiveness to vitality tests and sometimes tooth discoloration or radiographic signs of infection), treatment (root canal therapy) is needed promptly. So, the duration of “nerve damage” in terms of pain or non-responsiveness can be a temporary phase followed by healing (weeks to months) or a permanent state requiring intervention because healing is not possible. There isn’t a set time for irreversible damage to “heal” because it fundamentally doesn’t.

Can gums heal after trauma?

Yes, thankfully, gum tissue has a remarkable capacity for healing after trauma. The gingiva, being a soft tissue with a relatively good blood supply, responds well to injury and tends to heal much faster than bone or tooth ligaments. If the trauma causes lacerations (cuts) to the gums, these will typically start to close up within a day or two and can heal completely within one to two weeks, provided they are kept clean and there are no complications like infection. Larger or deeper lacerations might require sutures (stitches) to help hold the edges together for proper healing and to reduce scarring; these sutures are usually removed after about a week. Even if a flap of gum tissue has been displaced or partially torn, a dentist can often reposition it and suture it back into place, giving it a good chance of healing and reattaching to the underlying bone or tooth structure. Swelling and bruising of the gums around an injured tooth are also common and typically subside within a few days to a week. Good oral hygiene is crucial during gum healing – gentle cleaning around the injured area helps prevent infection, which could delay or complicate the healing process. While gums heal well from cuts and bruises, it’s important to distinguish this from loss of gum tissue height or volume due to severe trauma that might also damage the underlying bone or lead to tooth loss. While the remaining gum tissue will heal, lost gum tissue height (recession) generally does not grow back spontaneously to its original level, and more complex procedures like gum grafting might be needed later to restore the lost tissue. But for simple lacerations or contusions, gum healing is usually quite predictable and relatively quick compared to the recovery of the tooth itself or its supporting ligaments.

How long do torn gums take to heal?

Torn gums, meaning lacerations or cuts to the gingival tissue as a result of trauma, generally heal relatively quickly. The exact timeframe depends on the size, depth, and cleanliness of the wound, as well as whether stitches were needed. For minor lacerations that are clean and shallow, the edges will often start to seal within 24-48 hours, and the visible healing, with the tissue surface appearing normal, can be complete within approximately 7 to 14 days. You might still feel a bit of tenderness for a little longer. If the tear is larger, deeper, or irregular, or if a flap of tissue needed to be repositioned, the dentist will likely use sutures to hold the edges together. In these cases, the sutures help facilitate proper healing by keeping the wound closed and protected. The sutures are typically removed after about a week to 10 days, and the tissue continues to consolidate and strengthen over the next week or two. So, even with stitches, significant healing is usually achieved within 2 to 3 weeks. The key factors for optimal gum healing are cleanliness (gentle rinsing and careful brushing as advised by the dentist) and avoiding putting stress on the injured area. Infection, poor oral hygiene, or continued irritation can delay healing. While the surface tissue heals relatively fast, the underlying connective tissue might take a bit longer to regain full strength. But in terms of discomfort and visible wound closure, you’re generally looking at a recovery period of a couple of weeks for most gum lacerations treated properly.

Can gums regrow after trauma?

This is a common question, particularly if trauma results in visible gum recession or loss of gum tissue around a tooth. The simple answer is that while existing gum tissue has excellent healing capabilities and can repair cuts and tears, it does not typically “regrow” significant lost volume or height after trauma. If a severe injury causes the gum margin to recede significantly from its original position on the tooth, or if a large amount of gum tissue is lost due to impact or subsequent complications, the body will heal the remaining tissue, but it won’t spontaneously regenerate the lost gum structure back to its previous level. The tissue will cover the exposed bone or root to some extent through normal wound healing, but the original gum line often isn’t naturally restored. This is similar to how skin heals a deep wound with a scar rather than perfectly regenerating the original tissue structure and level. If the resulting gum recession is significant, exposing the tooth root and causing aesthetic concerns, sensitivity, or increased risk of root decay or periodontal problems, then reconstructive procedures like gum grafting may be considered by a periodontist. Gum grafting involves taking tissue from another area of the mouth (often the palate) or using donor tissue and surgically placing it in the area of recession to try and cover the exposed root surface and restore some of the lost gum height and thickness. So, while your body is great at healing minor gum injuries, it won’t regrow lost gum tissue on its own; regaining that lost volume requires surgical intervention.

How long do tooth ligaments take to heal?

The periodontal ligaments (PDL) are the unsung heroes of your mouth – a complex network of tiny fibers that suspend your tooth within the bone socket, allowing for slight movement and cushioning forces. Trauma, especially luxation injuries (like subluxation, extrusion, lateral luxation, intrusion) and avulsion (knocked out tooth), severely stretches, tears, or crushes these ligaments. Healing the PDL is crucial for the tooth to become stable again in its socket and maintain its connection to the bone. The healing process for these ligaments takes significantly longer than for soft tissues like gums. After a tooth is stabilized with a splint (which typically stays in place for a few weeks, depending on the injury type), the ligament fibers begin the slow process of repair and reattachment to both the tooth’s root surface (cementum) and the surrounding bone. This initial healing phase, where the ligaments start to regain enough strength to hold the tooth relatively firmly, can take weeks to a couple of months. However, the complete remodeling and maturation of the ligament structure is a much longer process, potentially taking several months, up to 6 months or even a year, particularly after severe injuries like avulsion or intrusion. The dentist will check the tooth’s stability periodically after the splint is removed to assess this healing. The success of PDL healing is critical because if it fails to heal correctly, complications like root resorption (where the body dissolves the root) or ankylosis (where the tooth fuses directly to the bone, losing its natural mobility) can occur, sometimes years down the line. While splinting supports the initial healing, the true biological recovery of the ligaments is a lengthy process requiring patience and continued monitoring.

What are the Complications of a Dental Injury?

Unfortunately, the story of dental trauma doesn’t always end happily ever after the initial treatment. Even with the best care, traumatic injuries to the teeth can lead to a range of complications, sometimes developing months or even years down the line. These complications can threaten the tooth’s long-term health, function, and even its continued presence in the mouth. They arise because the trauma can cause irreversible damage to the delicate structures within and around the tooth that aren’t always immediately apparent or fully rectifiable by initial treatment. The most common complications involve the tooth’s nerve, the root structure, and the connection between the tooth and the bone. Recognizing the signs and symptoms of these potential issues is incredibly important, both for the patient and the dental professional, which is why long-term follow-up after dental trauma is absolutely critical. Ignoring potential complications can lead to silent progression of damage, making later treatment more complex or impossible and ultimately resulting in the loss of the tooth. This section delves into the potential pitfalls that can follow dental trauma, highlighting why ongoing vigilance is necessary long after the initial pain has subsided and the visible repairs have been made.

Can trauma cause a root canal?

Yes, dental trauma is a very common cause for needing a root canal treatment, perhaps one of the most frequent long-term consequences. Root canal treatment is required when the tooth’s pulp (the nerve and blood vessels inside the tooth) becomes irreversibly damaged, infected, or necrotic (dies). Trauma can cause this irreversible damage in several ways. A fracture that extends deep enough to expose the pulp to the bacteria in the mouth environment will almost certainly lead to infection and death of the pulp if not treated immediately (sometimes partial pulp removal is attempted if the fracture is recent and in a young tooth, but full root canal is often necessary). Luxation injuries, where the tooth is significantly moved within its socket (like extrusion, lateral luxation, and especially intrusion – pushed into the bone), can stretch, compress, or completely sever the blood vessels and nerves entering the root tip. This cuts off the pulp’s vital supply, leading to its death. An avulsed tooth (knocked out) has its pulp supply completely severed; while the tooth can sometimes be replanted and the surrounding ligaments might heal, the pulp always dies and will require root canal treatment within a couple of weeks of replantation to prevent infection of the necrotic tissue. Signs that trauma might have caused nerve damage requiring a root canal include persistent or worsening pain, swelling, formation of a “pimple” or fistula on the gum near the tooth (indicating infection), or a gradual grey or dark discoloration of the tooth over time (signaling internal bleeding or nerve death). Pulp necrosis is often painless in its later stages, which is why follow-up vitality testing after trauma is so crucial to detect it before infection sets in. In essence, if trauma significantly compromises the tooth’s internal biology, a root canal becomes necessary to save the tooth.

Complications of a Dental Injury Explained

Dental trauma can lead to a variety of unwelcome complications, sometimes emerging long after the initial injury appears to have healed. Understanding these is key to long-term management.

-

- Pulp Necrosis: As discussed, severe trauma can cut off the blood supply to the pulp, leading to nerve death. This often requires root canal treatment to prevent infection. It may be painless initially but can lead to an abscess if untreated.

-

- Infection (Abscess): This is a direct consequence of untreated pulp necrosis. Dead pulp tissue becomes infected by bacteria, leading to pus formation, swelling, pain, and potentially bone destruction around the root tip. An abscess requires drainage and root canal treatment (or extraction).

-

- Root Resorption: This is a serious and complex complication where the body’s own cells start to break down and resorb (dissolve) the tooth root. It can be external (starting from the outer surface of the root) or internal (starting from within the pulp chamber/canal). Trauma is a major trigger for various types of root resorption, particularly inflammatory resorption following luxation or avulsion, and replacement resorption (leading to ankylosis). Resorption is often painless in its early stages and is detected via routine follow-up X-rays. Treatment, if possible, depends on the type and stage of resorption but can involve root canal therapy or even surgical intervention, though the prognosis can be poor.

-

- Ankylosis: This occurs when the tooth root fuses directly to the surrounding bone, losing its natural periodontal ligament space and slight mobility. It often follows severe trauma, particularly intrusion or avulsion, and is sometimes considered a form of replacement resorption where bone replaces the resorbing root. Ankylosed teeth can become submerged over time (especially in growing children) and are difficult or impossible to move orthodontically. They can eventually be lost.

-

- Discoloration: A traumatized tooth can change color. Pink or red discoloration immediately after injury might indicate internal bleeding in the pulp. A gradual grey or dark discoloration over weeks or months typically signals pulp necrosis. While some minor discoloration might fade, persistent grey usually means the nerve has died and requires root canal treatment, often followed by internal bleaching or a crown for aesthetic reasons.

-

- Delayed Eruption/Developmental Issues (in children): Trauma to primary (baby) teeth can sometimes affect the development or eruption path of the underlying permanent tooth bud, potentially leading to enamel defects (like discoloration or pitting), altered tooth shape, or delayed/ectopic eruption of the permanent tooth.

-

- Tooth Loss: Sadly, despite best efforts, severe trauma or complex complications can ultimately lead to the loss of the injured tooth.

- Periodontal Bone Loss: Severe luxation or fractures can also damage the bone supporting the tooth, potentially leading to long-term bone loss around the root.

These complications highlight why continuous monitoring with clinical exams and X-rays is absolutely vital after dental trauma.

Can teeth shift after trauma?

Yes, teeth can definitely shift after trauma, both immediately and sometimes over time as a complication. The most obvious example of immediate shifting occurs with luxation injuries. In a lateral luxation, the tooth is pushed sideways within the socket. In an extrusion, it’s pulled partially out, making it look longer. In an intrusion, it’s pushed inwards, making it look shorter or even disappearing into the gum. In these cases, the tooth’s position shifts dramatically at the moment of impact because the force tears or stretches the periodontal ligaments. Dentists treat these by manually repositioning the tooth back into its correct place and then stabilizing it with a splint. However, even after successful repositioning and splinting, slight shifts can sometimes occur during the healing period if the splint is damaged, comes loose prematurely, or if there’s significant damage to the bone socket. Furthermore, complications that develop later can cause teeth to shift. If a tooth undergoes ankylosis (fusing to the bone) and the surrounding bone continues to grow (especially in growing children), the ankylosed tooth can appear to “submerge” or sink relative to the adjacent teeth, which is a form of shifting relative to the bite plane. Severe root resorption can weaken the tooth’s support, potentially leading to increased looseness and drifting over time. Also, if trauma causes significant bone loss around the tooth, its stability can be compromised, potentially allowing it to shift. So, while immediate shifting is characteristic of luxation injuries and addressed by repositioning and splinting, delayed shifting can occur as a consequence of complications like ankylosis or bone loss, emphasizing the need for long-term monitoring.

Can a grey tooth turn white again?

Tooth discoloration, particularly turning grey or dark, is a common and often alarming consequence of dental trauma. It typically indicates that the tooth’s pulp (nerve) has been damaged or has died (necrosis) due to the injury. The grey color is often caused by the breakdown products of blood cells and nerve tissue that have seeped into the microscopic tubules within the dentin of the tooth. Can a grey tooth turn white again on its own? Generally, no. Once the pulp has died and caused this type of intrinsic (internal) staining, the tooth will not spontaneously regain its original white color because the vital tissue that maintained its health and appearance is gone. Very rarely, if the trauma caused only temporary internal bleeding without nerve death, the pinkish discoloration that might appear shortly after injury could fade over time. However, the persistent grey discoloration characteristic of necrosis is permanent without intervention. To restore the white appearance of a grey, non-vital tooth, dental treatment is required. The first step usually involves root canal treatment to remove the dead pulp tissue, as leaving it can lead to infection. After a successful root canal, the internal space can sometimes be used for internal bleaching, where a special bleaching agent is placed inside the tooth for a period of time to lighten the dentin from within. This can be quite effective in restoring a natural color. If internal bleaching isn’t sufficient or isn’t an option, or if the tooth is also structurally compromised, then cosmetic restorations like a veneer (a thin porcelain or composite shell bonded to the front surface) or a crown (a cap covering the entire tooth) can be used to cover the discolored tooth and restore its white appearance and shape. So, while the tooth won’t turn white by itself, modern dentistry offers effective ways to make a grey tooth appear white again after appropriate treatment for the underlying nerve damage.

Can a Dental Injury Be Prevented?

While you can’t completely eliminate the possibility of an unexpected accident, a significant portion of dental trauma is preventable or at least has its severity greatly reduced through conscious effort and taking proactive steps. Many dental injuries happen during activities where impacts to the face are foreseeable risks, such as sports, or they occur in common scenarios like falls that can be mitigated. Prevention focuses on minimizing exposure to risk factors and using protective gear when risks are unavoidable. It’s about being mindful of potential hazards in your environment and taking simple, common-sense precautions that can make a world of difference. Shifting the focus from just treating injuries to actively preventing them is a crucial public health message in dentistry, particularly for vulnerable populations like children and athletes. While helmets protect the head, they don’t necessarily protect the teeth, and while seatbelts are mandatory, facial impact can still occur. Therefore, understanding specific strategies dedicated to safeguarding your smile is an essential piece of the puzzle in maintaining long-term oral health and avoiding the pain, expense, and potential long-term complications associated with dental trauma.

How can I reduce my risk for dental trauma?

Reducing your risk for dental trauma isn’t about living in a bubble; it’s about smart precautions, especially during activities that carry inherent risks. Here are actionable ways to protect your teeth and mouth:

-

- Wear a Mouthguard During Sports: This is arguably the single most effective way to prevent dental trauma in children and adults participating in contact sports or activities with a risk of falls or impacts. This includes martial arts, boxing, football, basketball, soccer, hockey, lacrosse, skateboarding, cycling (especially mountain biking), gymnastics, and even activities like skiing or snowboarding. Mouthguards absorb and distribute the force of an impact, significantly reducing the risk of fractured, chipped, or knocked-out teeth, as well as protecting lips, cheeks, and jaws. Custom-fitted mouthguards made by your dentist offer the best protection, fit, and comfort compared to boil-and-bite or stock versions.

-

- Use Seatbelts and Car Seats: Ensure everyone in a vehicle is properly restrained. Seatbelts prevent facial impact with the steering wheel or dashboard during accidents. Use appropriate car seats and booster seats for children according to their age and size.

-

- Childproof Your Home: For young children, secure furniture that could tip over, install safety gates on stairs, use cushioned corner protectors on sharp edges of tables and counters, and ensure play areas are free of hazards they could fall onto.

-

- Wear a Helmet: While primarily for head protection, helmets (for cycling, skateboarding, skiing, etc.) can also offer some indirect protection to the face during falls.

-

- Avoid Using Your Teeth as Tools: Don’t use your teeth to open bottles, tear packaging, bite thread, or hold things while your hands are full. This puts excessive, unnatural force on specific teeth and can easily cause chips or fractures. Get the right tool for the job!

-

- Be Mindful of Your Surroundings: Simple awareness when walking on uneven surfaces, going up or down stairs, or navigating crowded spaces can help prevent falls.

- Maintain Good Oral Health: While it doesn’t prevent trauma, having strong, healthy teeth and gums makes them more resilient to injury and improves the prognosis if trauma does occur.

Implementing these simple strategies can significantly decrease your chances of experiencing a painful and potentially complicated dental injury. Prevention truly is better than cure in the realm of dental trauma.

How common is dental trauma?