Key Takeaways

- Bridge dentistry is a cornerstone of restorative treatment, offering a reliable, fixed solution for missing teeth.

- A dental bridge is a custom-designed, non-removable prosthetic device fabricated as *one cohesive piece*.

- It’s used to replace one or more missing teeth, reinstating function, preserving facial structure, and restoring smile confidence.

- Understanding the different types (Traditional, Maryland, Cantilever, Implant-Supported) and *materials* (Zirconia, Ceramic, PFM) is crucial for choosing the right option.

- The procedure typically takes *multiple appointments* over several weeks, involving preparation, temporary placement, fabrication, and final cementation.

- While generally not painful during the procedure (thanks to anesthesia), mild temporary discomfort and an *adjustment period* for chewing/speaking are expected afterwards.

- Advantages include restoring chewing/speech, improving aesthetics, and preventing tooth shifting, but disadvantages involve preparing adjacent teeth (for some types) and potential long-term complications like decay under crowns or gum disease.

- Cost varies widely ($4,500 – $15,000+ before insurance for a 3-unit bridge) based on type, materials, and complexity.

- Lifespan is typically 5-15 years, heavily dependent on *meticulous oral hygiene*, regular dental check-ups, and the health of the supporting teeth/implants.

- Alternatives include dental implants (more stable, bone-preserving, but higher initial cost) and removable partial dentures (less expensive, but less stable and comfortable).

In the intricate landscape of oral health, missing teeth present more than just an aesthetic dilemma. They disrupt the delicate balance of your bite, invite remaining teeth to embark on unwelcome migratory journeys, and can chip away at your confidence, making you hesitant to flash that natural expression of joy. Enter **bridge dentistry**, a cornerstone of restorative treatment that has, for decades, provided a reliable, fixed solution to bridge these gaps – quite literally. At its core, a dental bridge is a prosthetic marvel, a custom-designed device meticulously crafted to span the space left by one or more missing teeth. It’s a solution rooted in solid engineering principles, designed to reinstate function, preserve facial structure, and, crucially, restore that confident, radiant smile. Understanding what a bridge *is* in this specific dental context goes beyond a simple definition; it’s about grasping its role as a non-removable fixture, anchored securely in the mouth, standing as a permanent guardian against the cascade of issues triggered by tooth loss. The process, often referred to as getting a bridge “done,” involves several precise steps orchestrated by a skilled dental professional, beginning with careful assessment and preparation of the supporting structures, leading to the bespoke fabrication of the bridge itself, and culminating in its definitive, cementation-based placement. A point of common curiosity is whether this intricate restoration arrives as a single, monolithic unit. Indeed, a typical dental bridge is fabricated as one cohesive piece, uniting the artificial replacement tooth (or teeth) with its anchoring mechanisms. This unified structure is essential for its stability and function, allowing it to bear the forces of chewing effectively across the span of the missing tooth. The common uses and indications for choosing a dental bridge are varied and compelling, ranging from replacing a single lost tooth to several, particularly when the adjacent natural teeth are strong enough to act as dependable anchors. It’s a go-to option when implants aren’t feasible or desired, offering a fixed, stable alternative to removable dentures, thereby providing a consistent, reliable way to eat, speak, and smile without reservation. This foundational understanding sets the stage for appreciating the diverse types, materials, and processes that make bridge dentistry a vital tool in the modern dental arsenal, offering a pathway back to oral completeness and enhanced quality of life.

What Are the Different Types of Dental Bridges and What Materials Are Used?

Delving deeper into the world of dental bridges reveals a fascinating array of designs, each tailored to specific clinical scenarios and patient needs. The classification of these restorative devices primarily hinges on how they gain support – are they anchored by natural teeth, dental implants, or a combination? Understanding these distinctions is paramount when considering which solution is the optimal fit for a given situation, factoring in everything from the location of the missing tooth (or teeth) to the health and condition of the surrounding oral architecture. Alongside design, the choice of material plays a pivotal role, influencing the bridge’s strength, durability, aesthetics, and, perhaps most critically for many, its cost. Modern dental technology offers a sophisticated palette of materials, each with its unique set of advantages and considerations. Metals, ceramics, porcelains, resins – often used in combination – are the building blocks of these prosthetics, chosen based on the functional demands of the area (chewing forces in the back versus aesthetic prominence in the front), potential allergies, and, of course, budget. The expected lifespan or durability of a bridge is also intrinsically linked to both its type and the materials used; some designs, like traditional bridges, have well-established track records but rely heavily on the longevity of the supporting teeth, while others, like implant-supported versions, offer potentially longer lifespans by utilizing a more stable foundation. Navigating these options requires expert guidance, as determining the “best” type involves a comprehensive evaluation of the patient’s oral health status, the number and location of missing teeth, the condition of potential abutment teeth or bone structure for implants, and the patient’s personal preferences and financial situation. For instance, a cantilever bridge might be indicated in specific anatomical situations, while a Maryland bridge offers a more conservative approach suitable for certain cases, particularly involving front teeth. Cost is, undeniably, a significant consideration, and while general ranges exist, the final price tag is heavily influenced by the complexity of the case, the materials selected (zirconia, for example, is often more expensive than porcelain-fused-to-metal but offers superior strength and aesthetics), and the dental practice’s location and fee structure. Identifying the “cheapest” option often leads towards resin-bonded or certain metal-based designs, but it’s crucial to balance cost against factors like durability, aesthetics, and the potential long-term costs associated with premature failure. This intricate interplay of design, material, and individual circumstance underscores the need for a thorough consultation with a dental professional to arrive at a tailored solution that effectively and durably restores oral function and aesthetics.

What Defines a Traditional Dental Bridge?

The traditional dental bridge stands as the time-tested cornerstone of fixed tooth replacement, a true workhorse in restorative dentistry due to its widespread applicability and proven track record. At its core, this design is elegantly straightforward: it consists of one or more artificial teeth, known as pontics, suspended between dental crowns that are cemented onto the natural teeth adjacent to the gap. These adjacent natural teeth are technically referred to as the “abutment” teeth, acting as the pillars upon which the entire bridge structure relies for its stability and support. The process of preparing for a traditional bridge is a crucial step, involving the precise shaping or reduction of these abutment teeth. This preparation is necessary to create sufficient space for the crowns that will cap them, ensuring a proper fit and allowing the bridge to integrate seamlessly with the surrounding dentition without appearing bulky or unnatural. This shaping process, while routine, highlights the primary drawback of the traditional design: it requires modifying potentially healthy tooth structure on the abutment teeth, a consideration that influences the decision-making process when alternatives like implants are available. The most common configuration is the three-unit bridge, which replaces a single missing tooth positioned between two healthy teeth; the pontic replaces the missing tooth, and the two adjacent teeth receive crowns that are permanently attached to either side of the pontic, forming a single, connected unit. This unified fabrication, often carried out in a dental laboratory based on precise impressions of the prepared teeth, is critical. The strength of the bond created by the dental cement, combined with the structural integrity of the bridge itself, allows it to withstand the considerable forces generated during chewing and speaking. While highly effective, the success and longevity of a traditional bridge are inextricably linked to the health and strength of the abutment teeth. Any issue affecting these supporting pillars – decay beneath the crowns, gum disease compromising their support, or even root canal complications – can jeopardize the entire bridge. Despite this vulnerability, the traditional bridge remains a prevalent and valuable option, particularly when immediate placement of implants is not feasible, when multiple adjacent teeth are missing and conventional implants might be cost-prohibitive, or when the patient’s bone density is insufficient for implant placement without extensive grafting. Its reliability and relative simplicity, compared to the surgical nature of implants, make it a preferred choice for many seeking a fixed solution to tooth loss, providing a functional and aesthetic restoration that restores the smile and bite.

How Does a Maryland Bonded Bridge Work?

The Maryland bonded bridge, often referred to as a resin-bonded bridge, represents a distinctly different philosophy in fixed tooth replacement, prioritizing conservation of existing tooth structure. Unlike the traditional bridge which demands the shaping of adjacent teeth for crowns, the Maryland bridge typically requires minimal, if any, preparation of the abutment teeth. Its ingenious design centres around a pontic (the artificial tooth) that is fused or bonded to metal or porcelain wings or frameworks. These wings extend laterally from the pontic and are then securely bonded with a strong resin cement to the lingual (tongue-side) or palatal (roof-of-mouth side) surfaces of the adjacent natural teeth. The magic lies in this adhesive technique; by etching the enamel on the back of the abutment teeth and the inner surface of the wings, a micro-mechanical bond is created that, when coupled with potent dental resin, can hold the pontic firmly in place. This approach makes the Maryland bridge a particularly attractive option for replacing missing front teeth (incisors or canines), where the biting forces are generally less intense than in the back of the mouth, and where preserving the aesthetic integrity of the adjacent teeth is paramount. The minimal preparation means the procedure is less invasive, often requiring little to no drilling into the enamel or dentin of the supporting teeth. This makes it a potentially reversible treatment, as the bonding material can be removed with minimal lasting impact on the abutment teeth, a significant advantage over the irreversible reduction required for traditional crowns. However, this conservative nature comes with its own set of considerations. The strength of the bond, while considerable, relies heavily on the surface area available for bonding and the absence of moisture contamination during the cementation process. Consequently, Maryland bridges can be more susceptible to debonding or coming loose compared to their traditionally cemented counterparts, particularly if subjected to excessive forces or placed in areas with limited enamel surface for bonding. They are generally less suited for replacing posterior teeth (molars and premolars) or multiple missing teeth due to the higher chewing forces in these areas. Furthermore, the metal framework version, while potentially stronger, can sometimes cause a greyish shadow to show through the enamel of the abutment teeth, impacting aesthetics, especially in the upper front teeth. Porcelain or zirconia-based Maryland bridges offer improved aesthetics but can be more prone to fracture if not designed or bonded correctly. Despite these limitations, for the right clinical situation – typically replacing a single missing anterior tooth with healthy, strong adjacent teeth and sufficient enamel surface – the Maryland bridge provides an excellent, conservative, and less costly alternative, preserving natural tooth structure while effectively restoring the smile.

When is a Cantilever Dental Bridge an Option?

The cantilever dental bridge represents a unique design solution employed in specific clinical scenarios where the conventional need for abutment teeth on *both* sides of a missing tooth gap cannot be met. Its name itself, “cantilever,” derives from architectural engineering, referencing a structure that is supported only on one end. In the context of dentistry, this translates to a bridge design where the pontic (the artificial tooth replacing the missing one) is attached to only one or more abutment teeth on a single side of the gap. This contrasts directly with both traditional bridges, which require support from both mesial (towards the front) and distal (towards the back) sides, and Maryland bridges, which bond wings to adjacent teeth but typically still benefit from stabilization on both sides, even if minimal. The cantilever bridge is most often considered when there is a healthy, strong abutment tooth or multiple abutment teeth located only on one side of the edentulous space (the area where the tooth is missing), and there are no suitable teeth or planned implants on the other side to provide support. A classic example involves replacing a missing lateral incisor when only the adjacent canine tooth is strong enough to support the pontic. The pontic is then attached as an extension off the crown cemented onto the canine. Because the entire chewing load on the pontic is borne solely by the abutment tooth or teeth on one side, this design places significant stress on the supporting structure. Consequently, cantilever bridges are generally reserved for areas of the mouth that experience lower chewing forces, predominantly the anterior (front) teeth. While they *can* be used in some posterior situations, it is less common and carries a higher risk of complications, including fracture of the pontic, debonding of the crown from the abutment tooth, or even damage (such as tilting or loosening) to the supporting tooth itself due to excessive leverage forces. Careful case selection is critical for the success of a cantilever bridge. The abutment tooth must be exceptionally strong, healthy, and ideally have a large, well-supported root structure. The bite forces in the area must be thoroughly assessed, and the design and materials used must be robust enough to withstand the unilateral stress. While offering a solution when bilateral support isn’t an option, the cantilever design inherently carries a higher risk of mechanical complications compared to traditional bridges or implant-supported restorations due to the leverage forces acting on the pontic and abutment. Therefore, dentists approach this option with caution, meticulously evaluating the biomechanical factors to ensure the best possible prognosis for the restoration and the supporting tooth.

What is an Implant-Supported Dental Bridge?

Stepping into the realm of cutting-edge restorative solutions, the implant-supported dental bridge represents a significant leap forward, offering a highly stable and durable alternative to traditional tooth-supported bridges. This design completely bypasses the need to involve or modify adjacent natural teeth, a key advantage, especially when those teeth are healthy and unrestored. Instead, as the name explicitly states, this type of bridge is anchored directly onto dental implants surgically placed into the jawbone beneath the missing tooth or teeth. Dental implants are titanium posts that function as artificial tooth roots, fusing with the bone over time through a process called osseointegration, providing an incredibly solid and stable foundation. When replacing multiple missing teeth in a row, it’s not always necessary to place an implant for every single missing tooth. An implant-supported bridge allows for a series of pontics to be connected and supported by fewer implants; for example, two implants might support a three- or four-unit bridge replacing two or three missing teeth. This is particularly advantageous when extensive tooth loss has occurred, or when the adjacent natural teeth are not suitable candidates for traditional bridge abutments due to poor health, insufficient structure, or periodontal disease. The stability derived from the implant anchors is unparalleled by conventional bridges, leading to a restoration that feels remarkably secure and functions much like natural teeth. Furthermore, because the implants stimulate the jawbone, they help to prevent the bone resorption (shrinkage) that typically occurs after tooth loss when the root is no longer present. This preservation of bone structure is a crucial long-term benefit that traditional bridges cannot offer. Implant-supported bridges are often used to replace larger spans of missing teeth where traditional bridges would place too much stress on natural abutments, or as a fixed alternative to removable partial dentures. The procedure involves the surgical placement of the implants, followed by a healing period (typically several months) during which the implants integrate with the bone. Once integration is complete, abutments are attached to the implants, and the custom-fabricated bridge is then secured onto these abutments. While this option generally involves a higher initial cost and a longer treatment timeline compared to traditional bridges due to the surgical phase and healing period, its potential for greater longevity, superior stability, preservation of adjacent teeth, and stimulation of jawbone often make it a preferred choice for many patients and clinicians looking for a long-term, fixed solution. There’s also the possibility of **combination or hybrid designs**, where a bridge might be partially supported by implants and partially by natural teeth, though such designs are less common and require very careful planning and specific clinical conditions to be successful.

Comparing Dental Bridge Materials: Zirconia, Ceramic, and More

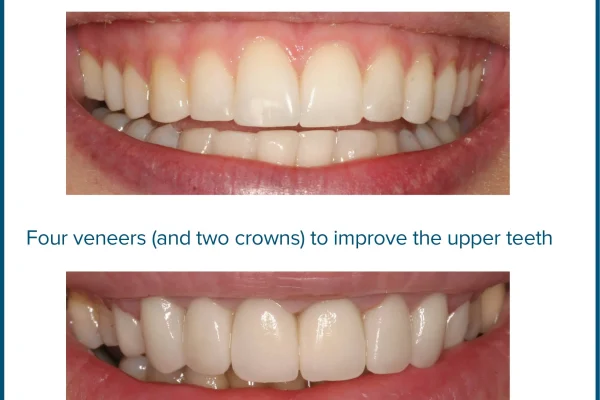

The materials used in the fabrication of dental bridges are as diverse as the designs themselves, each offering a unique balance of properties crucial for long-term success: strength to withstand chewing forces, aesthetics to blend seamlessly with natural teeth, biocompatibility within the oral environment, and cost-effectiveness. Understanding these materials is key to appreciating why one type of bridge might be recommended over another. **Zirconia**, a relatively newer material in dentistry, has rapidly gained popularity, particularly for posterior bridges and implant-supported restorations, due to its exceptional strength and fracture resistance. It’s often referred to as “ceramic steel” because it offers a robustness previously only associated with metal alloys, yet it possesses a tooth-coloured aesthetic quality. Zirconia bridges are often monolithic (milled from a single block of zirconia), making them incredibly durable, less prone to chipping than layered porcelain, and a good choice for patients who are heavy grinders or clenchers. While initially perceived as less aesthetic than traditional ceramics, advancements in multi-layered and translucent zirconia have significantly improved its appearance, making it suitable for some anterior applications as well. **All-Ceramic** materials, such as **Lithium Disilicate (commonly known by the brand name Emax)**, excel in aesthetics, offering excellent translucency and natural light-reflecting properties that mimic natural tooth enamel. These are often the preferred choice for anterior bridges where appearance is paramount. While not as inherently strong as monolithic zirconia, Emax is significantly stronger than traditional porcelains and can be used for short-span bridges, especially in areas with moderate biting forces. However, they may not be the best choice for long bridges or in areas of very high stress. **Metal-Ceramic** bridges, also known as porcelain-fused-to-metal (PFM), have been a staple of restorative dentistry for many years. They consist of a metal alloy coping (base) covered by layers of dental porcelain. The metal substructure provides excellent strength and durability, making PFM bridges suitable for both anterior and posterior regions, including longer spans. The porcelain provides the tooth-coloured aesthetic. The main drawbacks can be the aesthetic compromise sometimes seen near the gum line (a greyish line where the metal shows through), and the potential for the porcelain layer to chip or fracture over time, exposing the underlying metal. For patients seeking maximum strength without aesthetic concern (e.g., very far back molars or within certain budget constraints), **Full Metal** bridges made from gold alloys, nickel-chromium, or cobalt-chromium alloys are an option. They are exceptionally durable and resistant to fracture, requiring less tooth reduction than ceramic options. However, their metallic appearance is a significant aesthetic limitation, restricting their use primarily to areas not visible when smiling or speaking. **Acrylic** or **Resin-bonded** materials are typically used for temporary bridges worn while the permanent restoration is being fabricated. They are less durable and prone to wear and staining but serve effectively as an interim solution. **Fiber Reinforcement** can be incorporated into resin-bonded bridges to improve their strength, creating structures like fiber-reinforced composite bridges which offer a more aesthetic, metal-free option for some specific cases. The choice among these materials hinges on a careful balance of functional requirements (strength, durability), aesthetic goals (natural appearance), biological factors (biocompatibility, potential for allergic reactions), and economic considerations, all determined collaboratively between the patient and their dentist.

What Happens During the Dental Bridge Procedure and How Long Does it Take?

Embarking on the journey to receiving a dental bridge is a process marked by precision and collaboration between the patient, the dentist, and often, a skilled dental laboratory. It’s not typically a single-sitting affair, but rather a sequence of appointments, each building upon the last to create a custom-fitted, durable restoration that seamlessly integrates into your smile. The process typically commences with an initial consultation and examination, where the dentist assesses your overall oral health, evaluates the health and strength of the potential abutment teeth (or bone if implants are involved), takes X-rays and potentially 3D scans, and discusses the treatment plan, including the type of bridge and materials best suited for your situation. Once the decision is made to proceed with a traditional or cantilever bridge, the first active appointment focuses on **preparation**. This involves administering local anesthesia to numb the area, ensuring the procedure is comfortable. Then, the dentist carefully reshapes the abutment teeth. This preparation involves removing a precise amount of enamel and dentin to create space for the crowns that will fit over them. The degree of preparation varies depending on the type of bridge and material, but it is a permanent alteration of the natural tooth structure. Following preparation, the dentist takes highly accurate impressions (either traditional putty or digital scans) of the prepared teeth, the gap, and the opposing teeth. These impressions serve as the blueprint for the dental laboratory to fabricate your custom bridge, ensuring it fits perfectly and aligns correctly with your bite. While your permanent bridge is being crafted, which can take anywhere from one to a few weeks, the dentist will often place a **temporary bridge**. This interim restoration serves several crucial purposes: it protects the prepared abutment teeth from sensitivity and damage, maintains the space where the tooth is missing (preventing adjacent teeth from shifting), allows you to chew and speak relatively normally, and helps maintain the aesthetic appearance of your smile. This **fabrication process** in the dental lab is where skilled technicians use the impressions and materials chosen to meticulously construct the pontic(s) and crowns, ensuring precise fit, shape, and colour match. Once the permanent bridge is ready, you return for the second main appointment – the **final placement**. The temporary bridge is carefully removed, and the permanent bridge is tried in place. The dentist meticulously checks the fit, bite alignment, and aesthetics, making any necessary minor adjustments. If everything is satisfactory, the bridge is then permanently cemented onto the prepared abutment teeth using a strong dental adhesive. For implant-supported bridges, the process involves the initial implant surgery and a healing period before the bridge fabrication and placement steps occur, adding significantly to the overall timeline. Patients can typically expect a series of appointments spread over several weeks for conventional bridges, involving preparation, temporary placement, and final cementation, while implant-supported bridges extend this timeline considerably. Throughout this journey, open communication with your dentist about what to expect at each stage is vital, ensuring a smooth and predictable path to restoring your smile.

Is a Dental Bridge Procedure Done in One Day?

The short, unequivocal answer is typically no, a traditional or cantilever dental bridge procedure is generally *not* completed in a single day. The intricacy of creating a custom-fitted, durable restoration that seamlessly integrates with your unique oral anatomy necessitates a process that extends beyond a single appointment. While some preliminary assessments, like initial consultations and treatment planning, might occur in one visit, the core procedure unfolds over at least two main appointments, usually spaced several weeks apart. The first critical appointment is dedicated to the **preparation of the abutment teeth**. As detailed previously, this involves carefully numbing the area with local anesthesia and then precisely shaping the adjacent teeth that will serve as the anchors for the bridge. This step is non-negotiable for traditional and cantilever designs, as it creates the necessary foundation and space for the crowns that will support the pontic(s). Following this preparation, accurate impressions or digital scans are taken. These serve as the detailed blueprint that guides skilled technicians in a dental laboratory as they custom-craft the bridge. This laboratory phase is the primary reason the procedure cannot be finished in a day. Crafting a bridge from materials like porcelain-fused-to-metal, all-ceramic, or zirconia is a meticulous process involving multiple steps, including model creation, framework design (if applicable), layering or milling the restorative material, staining, glazing, and firing in specialized ovens. This fabrication process takes time – typically ranging from one to three weeks, sometimes longer depending on the complexity of the case and the lab’s workload. During this waiting period, a temporary bridge is usually placed to protect the prepared teeth, maintain space, and offer provisional function and aesthetics. The second main appointment occurs once the permanent bridge has been delivered from the lab. This visit involves removing the temporary bridge, trying in the permanent one to check for accurate fit, comfort, bite alignment, and appearance, and making any necessary minor adjustments. Only once the dentist and patient are satisfied is the bridge permanently cemented onto the prepared abutment teeth using a strong dental adhesive. For implant-supported bridges, the process involves the initial implant surgery and a healing period before the bridge fabrication and attachment can begin. While advancements in technology like in-office milling machines (CAD/CAM dentistry) allow for same-day crowns, fabricating entire multi-unit bridges with this technology is less common for complex cases and traditional designs, meaning the multi-appointment protocol remains the standard for the vast majority of dental bridge procedures.

How Long Does it Take to Recover After Getting a Dental Bridge?

The recovery period following the placement of a dental bridge is generally quite manageable, especially when compared to more invasive procedures like tooth extractions or implant surgery. For most patients receiving a traditional or cantilever bridge, the immediate aftermath is characterized by minimal discomfort, primarily related to the local anesthesia wearing off and the adjustment to a new prosthetic in the mouth. Once the numbness subsides, it is common to experience some mild soreness or sensitivity in the abutment teeth and surrounding gum tissue. This sensitivity might be felt when biting down or when exposed to hot or cold temperatures. However, this discomfort is typically transient and resolves within a few days to a week as the tissues heal and you become accustomed to the bridge. Over-the-counter pain relievers, such as ibuprofen or acetaminophen, are usually sufficient to manage any post-operative soreness. The most significant aspect of recovery isn’t necessarily physical pain, but rather the period of **adjustment** to chewing and speaking with the new bridge. A bridge replaces missing teeth, restoring the structure and surface area used for mastication. While this is the goal, your tongue, cheeks, and jaw muscles need time to get used to the presence of the pontic(s) and the altered bite forces. Initially, chewing might feel awkward or different. You might instinctively chew more cautiously, especially in the area of the bridge. This feeling of difference is perfectly normal and usually subsides as you gain confidence and familiarity with the restoration over the course of a week or two. Similarly, speech, particularly pronouncing certain sounds, might feel slightly different initially due to the new shape and presence of the bridge filling the gap. Again, this is a temporary phase of adaptation, and most people quickly adjust, with their speech returning to normal within a few days. Eating softer foods in the initial days after placement can help ease the transition. It’s also crucial to follow any specific post-operative instructions provided by your dentist, which may include guidance on oral hygiene during the initial healing phase around the gum line of the abutment teeth and pontic. For implant-supported bridges, the recovery timeline is different, as it includes the initial healing phase after implant surgery (which can take several months for osseointegration) before the bridge is even attached. However, once the bridge is attached to integrated implants, the adjustment period for chewing and speaking is similar to that of traditional bridges, typically just a week or two. Overall, while there’s a brief period of mild discomfort and adjustment, most patients can resume their normal activities, including eating a regular diet (with some caution regarding extremely hard or sticky foods), relatively quickly after the final placement of a dental bridge.

Can a Dental Bridge Be Removed or Recemented?

While dental bridges are designed to be permanent fixed restorations, the reality is that circumstances can arise where a bridge may need to be removed or, if it becomes loose but remains intact, potentially recemented. Understanding these possibilities is part of being fully informed about living with a dental bridge. There are several reasons a dentist might need to **remove a bridge**. One of the most common is the development of decay or infection in one or more of the abutment teeth underneath the crowns. Since the crowns cover the teeth, decay can sometimes go unnoticed until it becomes significant, potentially requiring the bridge to be removed to access and treat the affected tooth. Periodontal (gum) disease around the abutment teeth can also compromise their support, leading to mobility of the tooth and, consequently, the bridge. If the gum disease is advanced, removing the bridge might be necessary for comprehensive periodontal treatment or if the tooth prognosis is poor. Another reason for removal is the **failure of the bridge itself**. This could be due to a fracture of the pontic, a crack in one of the crowns, or catastrophic failure of the underlying abutment tooth. While well-made bridges using appropriate materials are durable, they are not indestructible. Finally, bridges sometimes need to be removed simply because they have reached the end of their lifespan (typically 5-15 years, though this varies widely) and require replacement due to wear, aesthetic decline, or the underlying abutment teeth needing attention. The process of removing a bridge requires precision and specialized tools to carefully break the cement seal without damaging the underlying teeth if they are to be reused. It is a procedure performed by a dentist and should never be attempted by the patient. Now, regarding **recementation**, if a dental bridge becomes loose but remains otherwise intact and undamaged, and if the underlying abutment teeth are still healthy and suitable, it may be possible for a dentist to clean the bridge and the prepared tooth surfaces and **recement it**. This often happens if the original cement seal has simply deteriorated over time, perhaps due to exposure to oral fluids or marginal breakdown. However, recementation is not always possible or advisable. The dentist will need to thoroughly inspect the bridge for damage and, more importantly, examine the abutment teeth for any new decay, cracks, or other issues that may have caused the bridge to loosen. If there is significant decay or damage to the abutment teeth, recementing the old bridge might not be a viable or long-term solution, and a new bridge or an alternative treatment like implants might be necessary. Repeated instances of a bridge coming loose can also indicate underlying issues with the fit, the abutment teeth, or excessive forces on the bridge, suggesting that recementation might only be a temporary fix. Therefore, while recementation is a possibility for a loose but intact bridge, it requires a professional assessment to determine if it’s the appropriate course of action or if a more definitive solution is needed.

Is Getting or Removing a Dental Bridge Painful?

The question of pain is a natural and valid concern for anyone considering a dental procedure, and it’s important to address it directly when discussing dental bridges. When it comes to **getting a dental bridge**, particularly the preparation phase for traditional or cantilever designs where abutment teeth are shaped, the procedure is typically performed under **local anesthesia**. This means the dentist will administer a numbing agent to the area around the teeth being worked on, effectively blocking pain signals from reaching the brain. You might feel a slight pinch or sting from the initial injection, but once the area is numb, you should not experience pain during the preparation itself. You might feel pressure or vibration from the dental drill, but not sharpness or pain. This significantly minimizes discomfort during the procedure itself. The potential for pain typically arises **after the local anesthesia wears off** (usually a few hours after the appointment). It is common to experience some mild to moderate soreness, tenderness, or sensitivity in the prepared abutment teeth and the surrounding gum tissue. This can manifest as sensitivity to pressure (especially when biting) or temperature (hot or cold). This post-operative discomfort is usually temporary and manageable with over-the-counter pain relievers like ibuprofen or acetaminophen and typically subsides within a few days. Placing a temporary bridge can also help reduce sensitivity in the prepared teeth. When the permanent bridge is cemented at the follow-up appointment, the process itself is generally painless, although some fleeting sensitivity to pressure or cold might occur. The primary sensation is one of the bridge being seated firmly onto the prepared teeth. Again, minor adjustment discomfort or sensitivity might occur for a short period after cementation. Now, considering the question of **removing a dental bridge**, this process can sometimes be more involved than placement, depending on how strongly it was cemented and the reason for removal. If the bridge is already very loose or has come off on its own, there might be minimal discomfort during removal. However, if the bridge is still securely bonded and needs to be carefully detached, the dentist will again use local anesthesia to ensure the procedure is comfortable. There might be pressure sensations as the bond is broken, but ideally, no sharp pain. If the reason for removal is significant decay or infection under the bridge, there might be pre-existing pain from that condition, and the treatment of the underlying issue might involve some discomfort, but the removal of the bridge itself will be made as comfortable as possible with anesthesia. In summary, getting a dental bridge is made pain-free during the procedure through the use of local anesthesia, with only mild, temporary post-operative discomfort expected. Removing a bridge, while potentially more complex, is also typically done with anesthesia to minimize discomfort, focusing on controlled detachment rather than causing pain.

What Are the Advantages and Disadvantages of Getting a Dental Bridge?

Choosing a dental bridge is a significant decision in restorative dentistry, and like any medical or dental procedure, it comes with its own set of advantages and disadvantages. Weighing these pros and cons is crucial for making an informed decision about whether a bridge is the right solution for your specific needs, particularly when comparing it to leaving a gap or considering alternatives like dental implants or removable dentures. A balanced understanding helps set realistic expectations about the treatment outcome and long-term maintenance. The primary allure of a dental bridge lies in its ability to offer a fixed, non-removable solution to tooth loss, providing a level of stability and convenience that removable options cannot match. This fixed nature means you don’t have to worry about taking it out for cleaning or while sleeping, contributing to a more natural feel and integration into daily life. However, this fixed nature also presents certain challenges, particularly regarding oral hygiene around the bridge. The necessity of involving adjacent teeth in the process, especially with traditional designs, introduces a potential long-term vulnerability if those supporting teeth are compromised. The materials used, while strong, are not immune to wear or fracture over time, and the bond holding the bridge in place can fail. Furthermore, while bridges restore the surface for chewing and speaking, they don’t address the underlying bone loss in the area where the tooth root is missing, a factor where implants hold a distinct advantage. The cost, while often less than multiple implants, represents a significant investment that may need to be repeated if the bridge fails prematurely or reaches the end of its lifespan. Therefore, the decision requires careful consideration of these factors, alongside individual oral health status, long-term goals, and potential financial implications, always in close consultation with a qualified dental professional who can provide personalized guidance based on a thorough clinical assessment.

What are the Benefits of Choosing a Dental Bridge?

Opting for a dental bridge offers a compelling array of benefits that contribute significantly to both oral health and overall well-being, making it a widely favoured restorative solution for missing teeth. One of the most immediate and impactful advantages is the **restoration of proper chewing function**. Missing teeth, especially molars or premolars, can make eating difficult, limiting dietary choices and impacting nutrition. A bridge fills this gap, providing a stable surface for mastication, allowing you to bite and chew food effectively, thus enabling a return to a more varied and enjoyable diet. Closely linked is the benefit of **improved speech**. Teeth play a vital role in articulating sounds. The absence of a tooth, particularly in the front of the mouth, can lead to speech impediments like lisping or whistling. A bridge replaces the missing tooth, restoring the correct structure needed for clear pronunciation. Beyond function, the **improvement of facial aesthetics** is a major driver for seeking tooth replacement. A visible gap in the smile can cause significant self-consciousness and reluctance to smile or speak openly. A bridge beautifully fills this void, restoring the natural appearance of the smile, boosting confidence, and enhancing overall facial harmony. By filling the space, a bridge also plays a crucial role in preventing the undesirable consequences of tooth loss on the surrounding dentition. When a tooth is lost, the adjacent teeth can begin to drift or tilt into the empty space, disrupting the bite alignment and potentially leading to problems like temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders, difficulty cleaning, and increased risk of decay or gum disease on the tilted teeth. The opposing tooth in the other jaw can also start to erupt further out of its socket (super-eruption) as it loses the counter-force of the missing tooth. A bridge acts as a space maintainer, holding the surrounding teeth in their correct positions and **preventing these undesirable shifts**. Furthermore, by replacing the missing tooth, the bridge helps to **distribute bite forces evenly** across the dental arch. When teeth are missing, the remaining teeth often bear excessive force, leading to accelerated wear, potential fracture, or increased stress on their supporting structures. The pontic in the bridge helps to redistribute these forces, protecting the remaining natural teeth. Finally, compared to the sometimes extensive process required for dental implants (which includes surgery and a significant healing period), the **treatment time for a traditional dental bridge is relatively quicker**, often completed within two to three appointments over a few weeks, offering a faster route to a fixed restoration for those seeking a more immediate solution. These combined benefits underscore why many individuals who have lost teeth choose a dental bridge to effectively and efficiently restore function, aesthetics, and the overall health of their bite.

What are the Potential Risks and Problems Associated with Dental Bridges?

While dental bridges offer significant benefits, it’s equally important to be aware of the potential risks, complications, and problems that can arise, as they are not without their drawbacks. Perhaps the most frequently cited disadvantage of **traditional bridges** is the **necessity of preparing (shaping) healthy adjacent teeth**. This involves removing a significant amount of natural tooth structure to accommodate the crowns, an irreversible process. If the abutment teeth were originally healthy and unrestored, this preparation means they will always require a crown or similar restoration in the future, even if the bridge is eventually removed. This invasiveness can also **increase the risk of decay or nerve damage** in the abutment teeth. Despite the crown, decay can sometimes start at the margin between the crown and the tooth, potentially progressing to the nerve and requiring a root canal treatment or even extraction of the abutment tooth, which would, in turn, lead to the failure of the entire bridge. Similarly, the preparation process itself, while generally safe, can occasionally irritate the nerve, leading to the need for root canal treatment. Maintaining meticulous oral hygiene around a bridge can be challenging, especially cleaning underneath the pontic (the artificial tooth). If not cleaned properly, food particles and bacteria can accumulate, leading to **gum disease** (gingivitis or periodontitis) affecting the gums and bone supporting the abutment teeth. Progressive gum disease can weaken the support structure, ultimately leading to the loosening and failure of the bridge. Another significant risk is the possibility of **bridge failure** itself. This can manifest as a fracture of the porcelain or ceramic material, chipping, debonding (the bridge coming loose from the abutment teeth), or in severe cases, a fracture of the underlying metal framework or even one of the abutment teeth. Excessive chewing forces, grinding (bruxism), using the bridge to bite on hard objects, or simple wear and tear over time can contribute to such failures. Unlike dental implants which integrate with the bone and help preserve it, dental bridges **do not prevent bone loss** in the area where the tooth root was missing. Over time, the jawbone in this area can shrink (atrophy), which can sometimes lead to a visible defect or gap under the pontic, affecting aesthetics and allowing food to get trapped more easily. Less common but potential problems include **allergic reactions** to materials used, particularly metal alloys. Some patients may also experience discomfort or pain if the bite is not perfectly aligned after placement. Addressing concerns like whether bridges can cause **bad odors** is also relevant; while the bridge itself doesn’t smell, poor hygiene leading to trapped food and bacteria can certainly cause halitosis (bad breath) and increase the risk of decay under the bridge. Similarly, **teeth under a bridge can absolutely still decay** if they are not properly cleaned and maintained, making diligent oral hygiene and regular dental check-ups paramount for the longevity and success of the restoration and the health of the supporting teeth. These potential issues highlight the importance of careful patient selection, proper bridge design, excellent fabrication, and, most critically, dedicated long-term oral hygiene and professional maintenance.

How Much Does a Dental Bridge Cost? Understanding the Investment

Navigating the financial aspect of dental treatments is a crucial part of the decision-making process, and understanding the cost of a dental bridge involves acknowledging that there is no single, fixed price tag. The **cost of a dental bridge varies widely**, often falling within a broad range that is influenced by a multitude of factors. Providing general cost ranges can offer an initial estimate, but it’s imperative to obtain a personalized quote from your dentist based on your specific case. On average, a traditional dental bridge replacing a single missing tooth (a three-unit bridge) can range anywhere from $1,500 to $5,000 or more per unit, with the total cost depending on the number of units involved. For example, a three-unit bridge would involve three units (two crowns and one pontic), placing it potentially in the $4,500 to $15,000+ range before insurance. However, these are just rough estimates, and the actual cost can be higher or lower. Several **key factors significantly influence the overall cost**. Chief among these is the **number of teeth being replaced**; replacing multiple teeth requires a longer bridge with more pontics and potentially more abutment teeth, substantially increasing the cost. The **type and material of the bridge** also play a critical role. Maryland bridges, being less invasive and often using less material, can sometimes be less expensive than traditional bridges, although complex designs or high-end aesthetic materials can increase their cost. The material chosen for the bridge’s fabrication is a major cost determinant; for instance, all-ceramic and zirconia bridges are often more expensive than porcelain-fused-to-metal (PFM) or metal-only bridges due to the cost of materials and the complexity of fabrication. **The complexity of the case** itself is another significant factor; challenges like misaligned abutment teeth, the need for preliminary procedures (like gum treatment or core build-ups on abutment teeth), or complicated bite issues can add to the overall cost. The **location of the dental practice** also influences pricing, with costs generally higher in urban or affluent areas. Finally, **dental insurance coverage** can significantly impact the out-of-pocket expense. Many dental insurance plans provide coverage for dental bridges as they are considered a major restorative procedure, but the extent of coverage varies greatly depending on the plan – some may cover 50%, while others offer less, and there are often annual maximums. Patients should always check with their insurance provider to understand their specific benefits. Addressing specific cost questions, such as **how much for a 2 teeth bridge?** (which would likely be a 4-unit bridge, replacing two missing teeth with crowns on two adjacent abutment teeth), or **how much is a fixed bridge?** (referring broadly to any non-removable bridge type), requires considering all the factors mentioned above. While general numbers exist, a personalized quote from your dentist, detailing the proposed treatment plan, materials, and estimated insurance coverage, is the most accurate way to understand the true investment required for your dental bridge.

How Long Do Dental Bridges Typically Last and What Causes Failure?

One of the most pressing questions for anyone investing in a dental bridge is its longevity: **how long will a dental bridge last?** While designed as a permanent fixture in your mouth, a dental bridge is not meant to last forever. Think of it as a high-performance component in a complex system; its lifespan is influenced by many variables. Generally speaking, the expected lifespan for traditional dental bridges ranges from **5 to 15 years**, although it is not uncommon for well-maintained bridges to last for 20 years or even longer in some cases. However, this is a broad average, and the actual duration can be significantly shorter or longer depending on a confluence of factors. Several elements play a critical role in determining **how long a bridge will truly last**. **Oral hygiene** is arguably the most significant factor; diligent and effective cleaning around the bridge and the supporting teeth is paramount to preventing the issues that lead to failure. **Dietary habits** matter too; consistently biting on hard candies, ice, or using the bridge to open packages can place excessive stress on the restoration and supporting teeth, leading to premature wear or fracture. Regular professional maintenance through **dental check-ups and cleanings** is also non-negotiable; these visits allow the dentist and hygienist to monitor the health of the abutment teeth and gums, detect any early signs of decay or gum disease, and identify potential problems with the bridge itself before they escalate into costly failures. The **overall health of the supporting structures**, namely the abutment teeth and gums, is perhaps the most fundamental determinant of a traditional bridge’s lifespan. A bridge is only as strong as its anchors. If the abutment teeth develop decay, fracture, or if the surrounding gum and bone tissue are compromised by periodontal disease, the foundation of the bridge is weakened, inevitably leading to its failure. Understanding **what causes bridge failures** is key to maximizing their lifespan. Common reasons include: **Recurrent decay** beneath the crowns on the abutment teeth, which weakens the tooth structure supporting the bridge. **Periodontal disease**, leading to loss of bone support around the abutment teeth and subsequent loosening of the bridge. **Fracture of the bridge material** (pontic or crown) due to excessive forces, grinding, or material fatigue over time. **Debonding or loosening** of the bridge from the abutment teeth, often due to cement washing out or underlying issues. **Fracture of an abutment tooth**, which is a catastrophic failure necessitating removal of the bridge and potentially extraction of the tooth. While Maryland bridges can be more prone to debonding, traditional bridges face risks primarily related to the health of the crowned abutment teeth. Implant-supported bridges, while more durable and not susceptible to decay of abutment teeth, can still experience issues like screw loosening, porcelain chipping, or complications with the implants themselves (though implant failure rates are low). Recognizing these potential points of failure underscores why meticulous care, both at home and professionally, is essential for achieving the maximum possible lifespan from your dental bridge.

How Can You Extend the Lifespan of Your Dental Bridge?

Extending the lifespan of your dental bridge beyond the average expectation is not a matter of luck; it’s a direct result of commitment to diligent care and proactive maintenance. Think of your bridge as a significant investment – protecting that investment requires consistent effort and attention to detail. The single most critical factor in ensuring your bridge lasts as long as possible is **maintaining impeccable oral hygiene**. Bacteria and food particles can easily get trapped under the pontic (the artificial tooth) and around the margins of the crowns on the abutment teeth. Because you cannot floss between the pontic and the gum like you can with natural teeth, specialized tools are necessary. Using **floss threaders**, **interdental brushes**, or a **water flosser (oral irrigator)** are highly recommended methods for cleaning the space underneath the pontic and around the abutment teeth where a regular toothbrush cannot reach effectively. Your dentist or dental hygienist can demonstrate the proper techniques for cleaning your specific type of bridge. Brushing twice daily with fluoride toothpaste is still essential for cleaning the surfaces of the crowns and abutment teeth and maintaining the health of the surrounding gums. Beyond daily cleaning, your **dietary habits** play a role. While a bridge allows you to eat more normally, it’s wise to exercise caution with extremely hard, sticky, or chewy foods. Biting down on hard objects like ice or hard candies can risk fracturing the bridge material or, worse, damaging the supporting abutment teeth. Similarly, very sticky or chewy foods can potentially loosen the bridge over time. Choosing softer options for such items helps protect your restoration. Perhaps equally important as daily care is **regular professional maintenance**. Visiting your dentist and dental hygienist for check-ups and cleanings **every six months (or as recommended by your dentist)** is crucial. These appointments allow the dental team to thoroughly clean areas you might miss, check the health of your gums and abutment teeth, and inspect the bridge for any early signs of wear, damage, or loosening. Detecting issues early often means they can be addressed with simpler, less costly interventions before they lead to complete bridge failure. If you grind or clench your teeth (bruxism), discuss this with your dentist. They may recommend a nightguard to protect your bridge and natural teeth from excessive forces during sleep. By combining meticulous home care with regular professional oversight and making smart dietary choices, you significantly enhance the chances of your dental bridge serving you reliably for many years, maximizing your investment and keeping your smile healthy and intact.

What Should You Do If Your Dental Bridge Breaks or Falls Out?

Discovering that your dental bridge has broken, become loose, or completely fallen out can be an alarming experience, but knowing how to react promptly and appropriately is key to minimizing damage and ensuring the best possible outcome. The absolute first and most crucial step is to **contact your dentist immediately**. This is not a situation to delay addressing, as the underlying issue that caused the failure may require urgent attention, and leaving prepared abutment teeth exposed can lead to pain, sensitivity, decay, or shifting of adjacent teeth. Explain clearly what has happened – did it break, become loose, or completely detach? Was there pain involved? Try to describe the circumstances leading to the event. If the bridge has completely fallen out, and you are able to, **retrieve the bridge** if possible. Handle it gently and avoid attempting to force it back into place yourself, as this could cause damage to the bridge, the abutment teeth, or the surrounding tissues. Once retrieved, **store the bridge safely** in a clean container. If you can’t get to your dentist right away, you might place the bridge in a small bag or container with a tiny bit of water or saliva to keep it from drying out, particularly if it’s a temporary acrylic bridge or a porcelain bridge, though a permanent metal or zirconia bridge won’t suffer from drying. However, the priority is getting it to the dentist as soon as possible for evaluation. When you see your dentist, bring the bridge with you. The dentist will carefully examine the bridge itself to assess the nature and extent of the damage or determine why it came loose. More importantly, they will thoroughly examine the abutment teeth that supported the bridge and the surrounding gum tissue. They will look for signs of decay, fracture, infection, changes in bite, or issues with the original preparation or cementation that could explain the failure. Depending on the diagnosis, the dentist will then determine the best course of action. If the bridge is intact and the abutment teeth are healthy, it may be possible to **recement the bridge**. If the bridge is fractured or damaged, or if the abutment teeth are compromised (e.g., significant decay or fracture), the bridge likely cannot be salvaged. In such cases, a **new bridge** will need to be fabricated. This might involve preparing the abutment teeth again (if possible) and taking new impressions. If the abutment teeth are unsalvageable, alternatives like dental implants (if feasible) or a removable partial denture might be considered. Dealing with a broken or fallen bridge requires swift action and professional assessment. Never attempt to use super glue or other adhesives to reattach it yourself, as this can cause irreparable damage to the tooth and bridge, making subsequent professional treatment much more difficult. Your dentist is the only one equipped to properly diagnose the cause of the failure and recommend the appropriate repair or replacement solution.

How to Properly Care for a Dental Bridge and What to Expect While Living With One?

Living with a dental bridge should feel largely natural, allowing you to eat, speak, and smile with renewed confidence. However, to ensure its longevity and maintain optimal oral health, **proper care for a dental bridge** is essential and differs slightly from caring for natural teeth. Since a bridge is a fixed unit where the pontic (artificial tooth) is attached to the crowns covering the abutment teeth, you cannot simply floss through the contact points on either side of the pontic as you would with natural teeth. Food particles and plaque can easily get trapped in the space between the underside of the pontic and the gum line, as well as around the margins of the crowns. If these areas are not cleaned diligently, it can lead to bad breath, gum inflammation, and, most critically, decay on the abutment teeth underneath the crowns. Therefore, the cornerstone of bridge care is effectively cleaning the area beneath the pontic. This requires using specific tools designed for navigating this space. A **floss threader** is a popular tool; it’s a loop of stiff plastic that helps you thread regular dental floss under the pontic. Once the floss is underneath, you can move it back and forth to clean the underside of the pontic and the gum tissue below it. **Interdental brushes** with flexible wires or plastic cores, often shaped like small Christmas trees or cylinders, come in various sizes and can be inserted into the space under the pontic or between the bridge unit and adjacent natural teeth to gently brush away debris. **Water flossers (oral irrigators)** use a stream of pulsating water to remove food particles and plaque from hard-to-reach areas, including under bridges and around abutments. They can be a very effective tool for bridge hygiene, especially for those who find traditional threading difficult. Your dentist or dental hygienist can demonstrate how to use these tools correctly for your specific bridge design. Brushing your teeth and the surfaces of your bridge twice a day with fluoride toothpaste using a soft-bristled brush remains vital for cleaning the exposed surfaces of the crowns and abutments and maintaining overall oral hygiene. **What to expect while living with one?** Once the initial adjustment period passes (usually a week or two), a well-fitting bridge should feel comfortable and stable. It should allow you to chew food efficiently, restoring function. Speech should also return to normal as you adapt to the presence of the restoration. You should feel confident smiling and speaking. However, you should be mindful of the potential pitfalls: food trapping can occur if the space under the pontic is not adequately cleaned, necessitating regular use of hygiene aids. Sensitivity to hot or cold in the abutment teeth, while often temporary after placement, could recur if decay develops under the crowns. An ongoing awareness of these potential issues, coupled with proactive cleaning and regular dental visits, ensures that living with a dental bridge is a positive and functional experience for its intended lifespan.

Can You Eat and Drink Normally With a Dental Bridge?

One of the primary goals of getting a dental bridge is to restore your ability to eat and drink normally, and for the most part, this is absolutely achievable with a well-placed, properly functioning bridge. After the initial adjustment period – typically a week or two following permanent cementation, during which you might choose softer foods as you adapt to the feel of the bridge and any residual sensitivity subsides – you should be able to resume a regular diet. However, while you gain significant functional restoration, it’s wise to exercise a degree of caution with certain types of foods to protect your investment and extend the life of your bridge. **Eating normally** means being able to bite and chew most everyday foods comfortably and effectively. The bridge restores the biting surface and helps distribute chewing forces. You should be able to chew meats, vegetables, fruits, and grains without difficulty. However, dentists typically recommend avoiding extremely hard foods, such as biting directly into very hard candies, nuts with shells, or ice, with the bridge. These items can generate forces that could potentially chip the porcelain, fracture the bridge material, or even damage the underlying abutment teeth. Similarly, very **sticky or exceptionally chewy foods** like taffy, caramels, or certain types of crusty bread or bagels should be approached with caution. These can stick to the bridge and, with chewing force, exert pulling pressure that could potentially loosen the bridge over time. While instances of a bridge being pulled off by chewing gum are less common with modern strong cements, it remains a theoretical risk with exceptionally sticky substances. As for **specific questions**, **can you eat an apple with a dental bridge?** Yes, you absolutely can, but it’s generally advisable to cut the apple into slices rather than biting directly into it with your front teeth, especially if the bridge is in the anterior region. Biting into a whole apple requires significant shearing force that can be stressful on front restorations. **Can I drink coffee with a bridge?** Yes, drinking coffee or other beverages is perfectly fine with a dental bridge. However, similar to natural teeth or other dental restorations like crowns, the material of the bridge (particularly porcelain or resin components) can potentially stain over time, especially with frequent consumption of dark beverages like coffee, tea, or red wine. Maintaining good oral hygiene and regular dental cleanings will help minimize staining. **Can you chew normally with a bridge?** Yes, chewing should feel normal and comfortable once you’ve adjusted. The bridge is designed to replicate the function of missing natural teeth. The exception is initially when you might feel cautious or awkward, but this is temporary. The goal is full restoration of normal chewing ability without pain or instability. In essence, a dental bridge allows for a return to a largely unrestricted diet and normal eating habits, provided you exercise reasonable caution with foods that could subject the bridge to extreme forces or excessive stickiness, focusing on regular and proper cleaning afterwards.

Can Food Get Stuck Under a Dental Bridge?

Yes, **food can absolutely get stuck under a dental bridge**, and this is one of the key reasons why specialized cleaning techniques are necessary for proper bridge maintenance. Unlike natural teeth where there is a small space between the tooth and the gum line that can be cleaned with standard brushing and flossing, the pontic (the artificial tooth) of a dental bridge is designed to sit directly on or very close to the gum tissue over the area of the missing tooth. However, it does not fuse with the gum tissue, leaving a small gap or space underneath. This space, while intended to be minimal for comfort and aesthetics, is unfortunately an ideal spot for tiny food particles and plaque (a sticky film of bacteria) to accumulate. When you chew, especially fibrous or smaller food items, these particles can easily get pushed into this sub-pontic space. Because the bridge is a fixed unit, you cannot use regular dental floss to clean between the pontic and the adjacent teeth or between the pontic and the gum line directly from the top or side in the same way you would floss between two natural teeth. This trapped food and plaque can ferment, leading to unpleasant odors (which is why some people wonder if bridges smell – it’s usually the trapped debris causing the smell, not the bridge material itself) and providing a breeding ground for bacteria. This bacterial accumulation is problematic because it can lead to several issues: irritation and inflammation of the gum tissue directly underneath the pontic (gingivitis), increasing the risk of more serious periodontal disease affecting the bone support of the abutment teeth, and potentially contributing to decay on the undersides of the crowns covering the abutment teeth or on the exposed tooth structure near the margins if the bacteria and acids are left undisturbed. Therefore, the potential for food trapping underneath the pontic highlights the critical importance of diligent cleaning in this specific area. Using tools like floss threaders, interdental brushes, or a water flosser as demonstrated by your dental professional is crucial for effectively cleaning this space and removing trapped food particles and plaque, thereby preventing the associated problems and ensuring the health and longevity of your bridge and the supporting teeth and gums. It’s a small space, but ignoring it can lead to significant complications, making consistent, targeted hygiene a cornerstone of bridge care.

Do You Need to Remove a Dental Bridge for Sleep?

Absolutely not. One of the significant advantages of a **fixed dental bridge**, as opposed to a removable partial denture, is that it is **permanently cemented in place** by your dentist and is **not meant to be removed** by the patient at all, whether for cleaning, during the day, or certainly not for sleeping. This fixed nature is a key feature that provides the stability, comfort, and confidence that users of removable dentures often lack. The bridge is designed to function like your natural teeth, staying securely in your mouth 24 hours a day. Attempting to remove a permanently cemented bridge yourself is impossible without professional tools and techniques and would likely result in significant damage to the bridge, the abutment teeth, or both. This lack of daily removal is one of the aspects that makes a fixed bridge feel more like a part of your own anatomy than a prosthetic device. While removable dentures require daily removal for cleaning and soaking and are typically taken out at night to allow the gums and underlying tissues to rest, a dental bridge remains in place continuously. The cleaning of a fixed bridge is done *in situ* – meaning, while it’s in your mouth – using specialized tools like floss threaders, interdental brushes, or a water flosser to clean the areas that a regular toothbrush cannot reach, particularly underneath the pontic and around the abutments. Brushing the surfaces of the bridge and abutment crowns is also done with the bridge in place. The cement used to bond the bridge to the prepared abutment teeth creates a very strong, durable connection intended to withstand the forces of chewing and remain securely in place for years. Therefore, there is no requirement, or indeed any possibility for the patient, to remove a fixed dental bridge for sleep or any other reason. Its permanence is a core benefit, allowing you to go about your daily and nightly routines without thinking about taking your teeth out. The focus shifts from removal and soaking to meticulous in-place cleaning techniques to maintain the health of the bridge and the vital supporting structures underneath.

Who is a Good Candidate for a Dental Bridge? Eligibility and Considerations

Determining whether someone is a good candidate for a dental bridge involves a comprehensive assessment by a dentist, evaluating not just the space where a tooth is missing, but the overall health of the patient’s mouth and the potential supporting structures. The suitability for a dental bridge is highly dependent on several factors, with the health and strength of the adjacent teeth being perhaps the most critical determinant for traditional and cantilever designs. A **good candidate** for a traditional bridge generally has: **One or more missing teeth** in a row. **Healthy teeth adjacent to the gap** that can serve as strong and stable abutments. These teeth must be free from significant decay, large fillings that might compromise their structural integrity, or extensive periodontal disease. The **importance of strong, healthy abutment teeth** cannot be overstated; they will bear the load of the pontic(s) in addition to their own function, so they must be robust enough to withstand these combined forces over time. The **overall oral health** of the patient is also a major consideration. Active gum disease (periodontitis) must be treated and under control before placing a bridge, as compromised gum and bone support around the abutment teeth is a leading cause of bridge failure. The patient must also demonstrate a willingness and ability to maintain excellent oral hygiene, including using specialized tools to clean under and around the bridge, as poor hygiene significantly increases the risk of complications like decay in the abutments and gum disease. **Case selection and treatment planning considerations** are paramount. The dentist will assess the location and number of missing teeth, the condition of the prospective abutment teeth (including root length, shape, and bone support), the patient’s bite (occlusion), and any habits like teeth grinding. For a cantilever bridge, the abutment tooth must be exceptionally strong and ideally located in an area of lower bite force. For a Maryland bridge, there must be sufficient enamel surface on the back of the adjacent teeth for bonding, and it is generally best suited for replacing a single front tooth. If adjacent natural teeth are not suitable or if multiple teeth are missing, an implant-supported bridge might be considered, requiring sufficient bone density and overall health compatible with minor oral surgery. **Biomechanical considerations** related to bite forces and the leverage on the bridge and abutments are a key part of planning. While there isn’t a strict “ideal age” for getting a dental bridge, suitability is more dependent on dental development and the health of the supporting structures than chronological age itself. As long as the supporting teeth and tissues are healthy and stable, a bridge can be a viable option for both younger adults and older individuals. However, in younger patients whose jawbones are still developing, options like implants might be deferred until maturity, making a bridge a potential temporary or long-term solution. A patient who is not a good candidate might have extensive decay or large fillings in the potential abutment teeth, advanced periodontal disease, insufficient bone support, or a history of poor oral hygiene compliance. In such cases, alternative treatments like implants (after bone grafting if needed) or removable dentures might be more appropriate. The dentist will thoroughly evaluate these factors during the examination to determine if a dental bridge is a suitable, predictable, and long-lasting solution for restoring your smile.

What is the Ideal Age for Getting a Dental Bridge?

Addressing the question of the “ideal age” for getting a dental bridge requires understanding that suitability is less about hitting a specific chronological milestone and more about the biological maturity and health of the oral structures. While there isn’t a strict minimum or maximum age limit universally applicable to everyone, the general guideline is that traditional dental bridges are typically considered for **adults whose jawbones and natural teeth have fully developed**. For most individuals, this means generally waiting until late adolescence or early adulthood (usually around 18-20 years old or later), when the growth plates in the jaw have fused and the adult teeth are fully erupted and their root development is complete. Placing a fixed bridge, particularly one supported by natural teeth, in a jaw that is still growing or where tooth eruption is incomplete can lead to complications as the surrounding tissues change and the bite evolves. The bridge, being a fixed unit, cannot adapt to these growth-related shifts, potentially leading to premature failure or orthodontic issues. Conversely, there isn’t an upper age limit for getting a dental bridge solely based on age. Many older adults are excellent candidates for dental bridges, provided they meet the crucial criteria: they must have **healthy, strong teeth adjacent to the gap** (for traditional designs) or adequate bone structure (for implant-supported designs), **good overall oral health** (free from active periodontal disease or widespread decay), and the **ability and willingness to maintain diligent oral hygiene**. The success of a bridge in an older patient depends more on their physiological health and oral condition than on the number of candles on their last birthday cake. Factors that might make an older individual a less suitable candidate would be the same as for a younger person: compromised health of potential abutment teeth, advanced gum disease, insufficient bone support (unless implants are planned and grafting is an option), or medical conditions that might complicate healing or increase the risk of infection. Therefore, instead of focusing on an “ideal age,” the focus should be on the “ideal oral conditions.” A thorough examination by a dentist is necessary at any age to assess the health of the remaining teeth and gums, evaluate bone density, consider the bite, and determine if a dental bridge is a biologically sound and predictable long-term solution for tooth replacement based on the individual’s specific clinical situation and overall health status, ensuring the best possible outcome for the restoration and the rest of their dentition.

Are Dental Bridges a Good Option for Missing Front Teeth?