Table of Contents

ToggleKey Takeaways

- Surgical dentistry is a specialized field treating complex oral and facial conditions.

- It differs from general dentistry by involving more invasive procedures and requiring extensive specialized training.

- Common procedures include tooth extractions (especially wisdom teeth), dental implants, bone grafting, and corrective jaw surgery.

- While pain is managed *during* surgery with anesthesia, post-operative discomfort is expected and managed with medication.

- Like any surgery, oral surgery carries risks (infection, bleeding, nerve injury) but is generally safe when performed by qualified specialists adhering to best practices.

- Recovery time varies by procedure, requiring careful aftercare, including pain management, swelling control, and dietary restrictions.

What is Surgical Dentistry and How Does It Differ?

Stepping beyond the familiar territory of check-ups and fluoride treatments, surgical dentistry represents a distinct, often more complex, facet of oral healthcare. At its core, it involves surgical procedures performed within the oral cavity and the surrounding structures. This isn’t just about repairing cavities or cleaning teeth; it’s about addressing anatomical or pathological issues through invasive techniques. The scope is remarkably broad, encompassing everything from the relatively common extraction of a stubborn tooth to intricate procedures involving bone grafting, nerve repair, or the removal of cysts and tumors. What truly sets it apart from general dentistry is the level of training required and the nature of the problems it addresses. General dentists are the frontline caregivers, focused on preventative care, diagnosis, and basic restorative treatments like fillings, crowns, and bridges. Surgical dentists, or oral surgeons as they are more frequently called, undergo years of additional specialized training post-dental school, often including a residency in a hospital setting alongside medical residents. This rigorous education equips them with the knowledge and surgical skills necessary to manage complex anatomical regions, administer various forms of anesthesia, and handle potential complications that can arise from invasive procedures. While general dentists may perform some minor surgical procedures, such as simple extractions, the more involved cases – those requiring significant bone manipulation, complex extractions, or procedures in close proximity to major nerves and blood vessels – are typically the domain of the surgical specialist. Synonyms like oral and maxillofacial surgery highlight the expanding territory this specialty covers, reaching beyond the teeth and gums to include the entire facial skeleton and soft tissues. The instruments involved are also different; alongside standard dental tools, a surgical setup includes scalpels, specialized elevators, bone files, sutures, and drills designed for precision bone work, a stark contrast to the handpieces and mirrors of routine dental visits. Understanding this distinction is crucial for patients to know when their needs extend beyond the capabilities of a general dentist and require consultation with a surgical expert.

What is surgical dentistry?

Surgical dentistry, fundamentally, is the specialized field within dental medicine dedicated to diagnosing and treating diseases, injuries, and defects of the mouth, jaw, face, head, and neck through surgical intervention. It is a discipline that requires a deep understanding of anatomy, physiology, pathology, and surgical principles, extending far beyond the scope of routine dental practice. Think of it as the advanced combat unit of dentistry, brought in when the standard tools and techniques of general care aren’t sufficient to resolve the problem. Its focus is inherently invasive, dealing with tissues below the gum line, within the bone, or affecting the underlying skeletal structure of the face. This specialty covers a vast array of conditions that require surgical solutions, whether it’s removing tissue, repositioning bone, implanting foreign materials (like dental implants), or correcting structural deformities. It is a recognized specialization requiring extensive post-doctoral training, often involving hospital-based residencies that provide exposure to complex medical scenarios, trauma management, and advanced surgical techniques. Professionals in this field are adept at managing pain and anxiety through various anesthetic techniques, ranging from local anesthesia and conscious sedation to general anesthesia administered in outpatient or hospital settings. The goal of surgical dentistry is multifaceted: it aims to eradicate disease (like infections or tumors), repair damage (from trauma or tooth loss), correct structural abnormalities (like jaw misalignment), and restore function and appearance to the affected areas. It plays a critical role in maintaining overall oral and maxillofacial health, addressing problems that, if left untreated, could lead to chronic pain, significant functional impairment, or serious systemic health issues. It truly is a crucial pillar in the broader healthcare system, seamlessly integrating dental and medical principles to provide comprehensive care for conditions impacting one of the most vital and complex regions of the human body.

What Does Surgical Dentistry Consist Of?

The repertoire of procedures falling under the umbrella of surgical dentistry is extensive, covering a wide spectrum of treatments designed to address diverse oral and maxillofacial conditions. It certainly goes far beyond merely drilling and filling teeth or providing routine cleanings. This field encompasses a variety of interventions, broadly categorized into areas such as tooth extraction, dental implantology, corrective jaw surgery, treatment of oral pathology, management of facial trauma, reconstructive surgery, and treatment of temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders. To elaborate, tooth extractions, while sometimes performed by general dentists, become a core part of surgical dentistry when dealing with impacted teeth (like wisdom teeth), broken teeth, or teeth with complex root structures requiring surgical removal techniques. Dental implant surgery is a cornerstone, involving the precise placement of titanium posts into the jawbone to serve as anchors for replacement teeth – a procedure that often necessitates preliminary steps like bone grafting or sinus augmentation if bone density is insufficient. Corrective jaw surgery, or orthognathic surgery, addresses skeletal discrepancies in the jaw structure that affect bite alignment, chewing, speech, and facial aesthetics. Oral pathology involves the biopsy and removal of cysts, tumors, or other lesions found in the mouth or jaw. Facial trauma includes treating fractures of the jaw, cheekbones, or eye sockets, as well as lacerations to the face and mouth. Reconstructive surgery becomes necessary after trauma, disease, or congenital defects, involving grafting bone or soft tissue to rebuild missing structures. Management of severe TMJ disorders, when non-surgical methods fail, may involve surgical procedures on the joint itself. The treatment spectrum of dental surgery is vast, tailored to the specific needs and complexities of each patient’s condition. It requires not only precise surgical skill but also comprehensive pre-operative planning, including advanced imaging techniques like CT scans, and meticulous post-operative care management to ensure successful outcomes and minimize complications. The “Complex Oral Surgery Treatments are Designed Around Your Unique Needs” mantra highlights this personalized approach, recognizing that no two mouths or conditions are exactly alike, demanding a customized surgical plan for every individual case.

Dental Surgery vs. Oral Surgery: Clarifying the Differences

The terms “dental surgery” and “oral surgery” are frequently used interchangeably in everyday conversation, which can lead to understandable confusion. While they are closely related and often overlap significantly, there are subtle distinctions, particularly when considering the full breadth of the specialty. “Dental surgery” can sometimes be used more broadly to refer to any surgical procedure performed by a dentist within the oral cavity, including those procedures that might be done by a general dentist with some surgical training, such as a simple extraction or minor soft tissue procedures. It can also simply refer to the physical location where surgical dental procedures take place – i.e., a dental surgery practice or clinic. “Oral surgery,” on the other hand, almost invariably refers to the recognized dental specialty: Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. This specialty has a defined scope of practice that is taught in accredited post-doctoral residency programs. Therefore, while all oral surgery is technically a form of dental surgery (as it’s performed by a dentist), not all dental surgery is oral and maxillofacial surgery. An oral and maxillofacial surgeon is a highly trained specialist whose expertise extends far beyond the teeth and immediate surrounding soft tissues, encompassing the entire jaw, face, and even the skull. They are trained to handle complex bony procedures, nerve repair, facial trauma, and more intricate forms of pathology. Organisations like the British Association of Oral Surgeons (BAOS) define oral surgery specifically as dealing with the surgical management of diseases of the mouth, jaw, and face, often overlapping with aspects of general surgery, plastic surgery, and ENT surgery. In practice, for most patients, if a procedure is complex enough to require a specialist beyond a general dentist, they will likely be referred to someone whose title is Oral Surgeon or Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon, making “oral surgery” the more precise term for the specialized field and its practitioners, while “dental surgery” serves as a more general description of surgical interventions in the mouth area.

What is Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery?

Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery (OMS) is the most recognized and comprehensive surgical specialty within dentistry, often referred to simply as “oral surgery.” This field goes significantly beyond just teeth and gums, focusing on diagnosing and surgically treating diseases, injuries, and defects in the hard and soft tissues of the mouth, jaws, face, and neck. It’s a bridge between dentistry and medicine, requiring extensive training that typically includes a four-year dental degree (DDS or DMD) followed by a four-to-six year hospital-based surgical residency program. Many OMS programs also include earning a medical degree (MD) alongside their surgical training, providing these specialists with a unique dual perspective and the ability to manage complex medical patients in a hospital setting. The scope of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery is vast and includes a wide array of procedures. This ranges from routine dentoalveolar surgery, such as difficult tooth extractions (like impacted wisdom teeth), pre-prosthetic surgery (preparing the mouth for dentures or implants), and removal of cysts and tumors of the jaws and mouth, to more complex interventions. These complex procedures include dental implant surgery and associated bone grafting (like sinus lifts), corrective jaw surgery (orthognathic surgery) to fix misalignment of the jaws, surgical treatment of temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders, management of facial trauma (fractures of the jaw, cheekbones, eye sockets, and nose), and reconstructive surgery following trauma or disease. They also manage head and neck pathology, including benign and malignant tumors, and perform cosmetic procedures on the face. While the term ‘surgical dentistry‘ can broadly encompass procedures performed by dentists with surgical training, Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery specifically denotes this highly specialized field with its distinct, comprehensive scope extending to the entire maxillofacial region. It represents the pinnacle of surgical expertise within the dental profession, equipped to handle some of the most intricate and challenging conditions affecting the head and neck area through sophisticated surgical techniques.

What Happens During Oral Surgery?

Undergoing oral surgery typically follows a structured process, starting well before you even sit in the surgical chair. It begins with a thorough consultation where the surgeon reviews your medical history, performs a clinical examination, and uses diagnostic tools like X-rays or CT scans to assess your specific condition. This phase is crucial for diagnosing the problem accurately, determining the most appropriate surgical plan, discussing the procedure in detail, explaining potential risks and benefits, and addressing any questions you might have. Pre-operative instructions will be provided, which might include guidelines on eating and drinking before the procedure, adjusting medications, and arranging for transportation home, especially if sedation or general anesthesia is used. On the day of the surgery, you will be prepped, and the chosen type of anesthesia will be administered to ensure you are comfortable and pain-free during the procedure. This could range from local anesthesia to numb the specific surgical site while you remain fully awake, to conscious sedation (often administered intravenously) which makes you drowsy and relaxed, or even general anesthesia, where you are completely asleep. Once the anesthesia has taken effect, the surgeon will proceed with the planned surgical intervention, using specialized instruments to access the affected area, perform the necessary steps (like removing bone, extracting a tooth, placing an implant, or making repairs), and then meticulously close the surgical site, often with sutures. The duration of the procedure varies greatly depending on its complexity, from a quick simple extraction taking minutes to complex reconstructive surgery lasting several hours. Throughout the process, the surgical environment is maintained under strict sterile conditions to minimize the risk of infection. What you experience during the surgery depends heavily on the type of anesthesia; with local anesthesia, you’ll feel pressure and movement but no sharp pain, while with sedation or general anesthesia, you’ll likely have little to no memory of the procedure itself. Afterwards, you will be moved to a recovery area to be monitored as the effects of anesthesia wear off before being discharged with detailed post-operative instructions and prescriptions for pain medication and antibiotics if needed.

What Are the Common Types of Surgical Dental Procedures?

Surgical dentistry isn’t a single monolithic practice; rather, it’s a collection of specialized procedures designed to tackle a variety of oral and maxillofacial issues that cannot be resolved through non-surgical means. This section delves into the more frequently encountered surgical interventions you might encounter. Think of this as exploring the “treatment spectrum of dental surgery,” showcasing the range of problems that can be effectively addressed through these advanced techniques. It’s important to note that while some procedures are relatively routine for a trained surgeon, others can be quite complex, requiring intricate planning and execution. Indeed, “Complex Oral Surgery Treatments are Designed Around Your Unique Needs,” emphasizing that even common procedures can vary significantly in difficulty based on individual patient anatomy and the specific nature of their condition. The necessity for surgery often arises when there are issues with teeth that are unable to erupt properly, teeth that are damaged beyond repair by decay or trauma, insufficient bone structure for supporting dental restorations, problems with jaw alignment impacting function and aesthetics, or pathological conditions like cysts or tumors. These procedures are performed by skilled practitioners, primarily oral and maxillofacial surgeons, but also sometimes by general dentists with advanced surgical training or other specialists like periodontists (for gum surgery) and endodontists (for certain root-related surgeries). Understanding these common types helps demystify surgical dentistry and highlights the specific ways it can restore health, function, and comfort to the oral and facial regions.

What are the types of dental surgery?

The field of surgical dentistry encompasses several broad categories of procedures, each targeting different issues within the oral and maxillofacial region. One of the most common categories is Dentoalveolar Surgery, which deals with conditions affecting the teeth and the bone supporting them (the alveolus). This includes tooth extractions, particularly complex or impacted teeth like wisdom teeth, as well as procedures to prepare the mouth for dentures, such as smoothing or reshaping the jawbone (alveoloplasty). Another significant area is Dental Implant Surgery, which involves the placement of titanium posts into the jawbone to replace missing tooth roots and support prosthetic teeth (crowns, bridges, or dentures). This often requires adjunctive procedures like bone grafting or sinus lifts if there isn’t enough natural bone available. Corrective Jaw Surgery, also known as Orthognathic Surgery, addresses skeletal discrepancies where the upper and lower jaws don’t align properly, affecting bite, chewing, speech, and facial appearance. This type of surgery involves cutting and repositioning sections of the jawbone. Oral Pathology involves the surgical diagnosis and removal of cysts, tumors, and other benign or malignant lesions found in the mouth, jaws, or salivary glands. Management of Facial Trauma is a critical part of the specialty, involving the treatment of fractures of the facial bones (jaws, cheekbones, orbits) and lacerations to the soft tissues of the face and mouth. Reconstructive Surgery becomes necessary after trauma, disease, or congenital defects to rebuild missing hard and soft tissues, often using grafts from other parts of the body. Surgical treatment of Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ) disorders is also within the scope, ranging from minimally invasive arthroscopy to open joint surgery for severe cases. Periodontal Surgery, while primarily performed by periodontists, can also be considered a type of dental surgery, focusing on treating advanced gum disease through procedures like pocket reduction surgery, bone grafting, and soft tissue grafting to restore the health and support structures of the teeth. These diverse categories illustrate the comprehensive nature of surgical dentistry in addressing a wide array of oral and facial health challenges.

The Most Common Dental Surgery Procedures

While the list of potential surgical dental procedures is extensive, several stand out as being performed with greater frequency than others in most practices. At the top of this list, almost universally, is Tooth Extraction, particularly the removal of wisdom teeth. Wisdom tooth extraction is incredibly common because these third molars often don’t have enough space to erupt properly, leading to impaction, pain, infection, or damage to neighboring teeth. Both simple extractions (for visible teeth) and more complex surgical extractions (for impacted or broken teeth) fall into this category. Following closely is Dental Implant Placement. As dental implants have become the gold standard for replacing missing teeth due to their stability and longevity, the surgery to place the implant screw into the jawbone is now one of the most routine surgical procedures performed by oral surgeons and increasingly, by general dentists with specialized training. Procedures related to preparing the mouth for dentures or implants, known as pre-prosthetic surgery, are also very common. This includes reshaping the bone ridges (alveoloplasty) or removing excess gum tissue to ensure a proper fit for a prosthetic device. While less frequent than extractions or implants in the general population, procedures like Frenectomy (removal or reduction of a muscular attachment that restricts movement, often under the tongue or lip) or the surgical management of small oral lesions (like fibromas or mucoceles) are also relatively common minor surgical interventions. Periodontal surgery, such as flap procedures to access and clean infected roots and bone or gum grafting to treat recession, is also a frequently performed surgical procedure, though typically by a periodontist. These procedures represent the forefront of surgical intervention in dentistry, addressing prevalent issues that affect millions of patients annually, whether it’s alleviating pain from an impacted tooth, restoring the ability to chew with implants, or preparing the mouth for functional and comfortable prosthetics.

Exploring Specific Surgical Dental Procedures in Detail

Moving beyond the general categories, let’s delve deeper into some of the specific procedures that are frequently performed within surgical dentistry. Each of these procedures addresses particular issues and involves a unique set of steps and considerations. Understanding the specifics helps demystify what might otherwise seem daunting and highlights the precise nature of the surgeon’s work. From replacing missing tooth roots to realigning entire jaw structures, these detailed explorations reveal the intricate techniques employed to restore health, function, and form. We’ll look at what each procedure entails and the reasons why a patient might require it, providing a clearer picture of the ‘why’ and ‘how’ behind these common surgical interventions.

Dental Implant Surgery

Dental implant surgery is a sophisticated procedure designed to replace missing teeth in a way that mimics the natural tooth root structure. It’s widely regarded as the most durable and stable solution for tooth loss, offering a significant upgrade from traditional bridges or dentures in many cases. The process typically involves multiple stages, but the core surgical step is the precise placement of a dental implant – a small, biocompatible post, usually made of titanium, into the jawbone beneath the gum tissue. This implant serves as a stable anchor for a replacement tooth, whether it’s a single crown, a bridge, or even a full denture. The initial step involves preparing the site and surgically placing the titanium implant screw directly into the bone where the tooth root used to be. Following placement, a period of healing is required, often several months, during which the bone tissue fuses directly onto the implant surface in a process called osseointegration. This fusion is critical as it provides the necessary stability for the implant to function like a natural tooth root. Once osseointegration is complete, the next step is typically placing the abutment. This is a connector piece that screws into the implant and protrudes through the gum line, serving as the base onto which the final prosthetic tooth (the crown) will be attached. In some cases, if the implant is deemed stable enough at the time of placement, the abutment might be attached immediately, or a temporary crown might even be placed, though this is not always feasible. The entire process, from initial consultation and potential preliminary procedures like bone grafting to the final placement of the crown, can take several months. However, the outcome is a replacement tooth that is firmly anchored, looks and feels natural, and can last for decades with proper care, offering significant benefits in terms of chewing ability, speech, and aesthetics compared to removable options.

Corrective Jaw Surgery

Corrective jaw surgery, formally known as orthognathic surgery, is a surgical procedure performed by oral and maxillofacial surgeons to correct skeletal and dental irregularities of the jawbones. These irregularities can lead to misaligned bites (malocclusion), difficulty chewing, speaking, or breathing, and disproportionate facial appearance. Unlike orthodontic treatment (braces or aligners) which focuses on moving teeth within the jaw, orthognathic surgery addresses the underlying bone structure itself, repositioning the upper jaw (maxilla), lower jaw (mandible), or both, and sometimes other facial bones. The purpose of the surgery is to physically move the bones into their correct anatomical relationship to each other and to the rest of the facial skeleton. Reasons for needing corrective jaw surgery are varied but often involve significant malocclusion that cannot be fixed with orthodontics alone, facial asymmetry, difficulty closing the lips comfortably, excessive wear of teeth due to bite problems, or obstructive sleep apnea caused by the position of the jaws. Planning for this surgery is meticulous and involves close collaboration between the oral surgeon and an orthodontist. Orthodontics are typically worn before surgery to align the teeth within each jaw independently, preparing them for the new bite relationship post-surgery. Advanced imaging and 3D planning software are used to precisely map out the surgical movements. During the surgery, the surgeon makes cuts in the jawbones and repositions them according to the surgical plan, securing them in their new position with small titanium plates and screws, which are usually left permanently in place. The surgery is performed under general anesthesia and requires a hospital stay of usually one to three days. Recovery involves a period of swelling, restricted diet (often liquids initially, progressing to soft foods), and continued orthodontic treatment to fine-tune the bite. While a significant undertaking, corrective jaw surgery can dramatically improve not only oral function but also facial harmony and airway function, leading to profound positive impacts on a patient’s health and self-confidence.

Wisdom Tooth Extraction

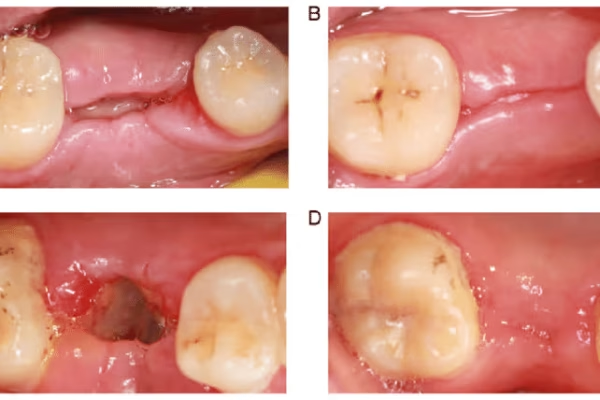

Wisdom tooth extraction is arguably the most commonly performed surgical procedure in dentistry, impacting a vast number of young adults globally. These teeth, the third and final set of molars, typically erupt between the ages of 17 and 25. However, modern human jaws are often not large enough to accommodate them, leading to what is known as impaction – where the wisdom teeth fail to erupt fully or at all, often remaining trapped beneath the gum line or bone, or emerging only partially. This lack of space and improper eruption can cause a cascade of problems. Impacted wisdom teeth can push against neighboring teeth, potentially causing damage or shifting. They are notoriously difficult to clean, even if partially erupted, making them susceptible to decay and gum infection (pericoronitis). Cysts or tumors can also form around an impacted wisdom tooth. Consequently, proactive removal is often recommended to prevent these complications, even if the teeth are not currently causing pain. So, to answer the direct question: Is wisdom teeth removal a surgery? Yes, absolutely. Even when a wisdom tooth has fully erupted, if it requires sectioning or significant manipulation to remove, it is classified as a surgical extraction. The procedure itself varies depending on the degree of impaction. For fully erupted teeth, it might resemble a complicated standard extraction. For impacted teeth, the oral surgeon typically needs to make an incision in the gum tissue to expose the tooth and underlying bone, potentially remove some bone obstructing the tooth‘s path, and often divide the tooth into smaller pieces to remove it more easily and with less trauma to the surrounding tissues. The site is then cleaned and usually closed with sutures. The complexity is largely determined by the tooth‘s position, angle, and proximity to important structures like nerves. Recovery involves swelling, discomfort, and strict adherence to post-operative instructions to prevent complications like dry socket.

Dental Bone Grafting

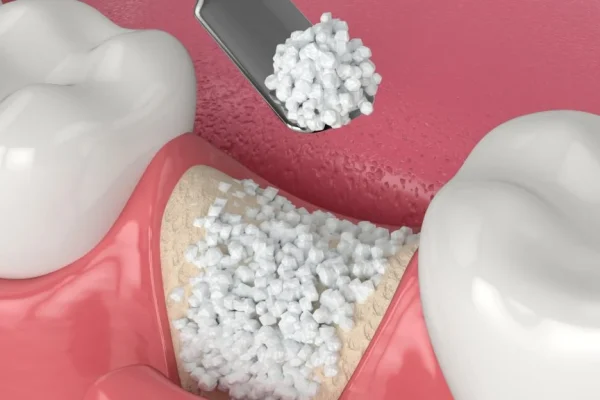

Dental bone grafting is a surgical procedure used to rebuild or supplement bone in the jaw. This is a critical technique in surgical dentistry, particularly in the context of tooth loss and the desire to place dental implants, but also for periodontal health and jaw reconstruction. Bone loss in the jaw can occur for several reasons: prolonged absence of teeth (the bone supporting the tooth root resorbs over time without the stimulation of chewing), periodontal disease which destroys the bone around teeth, trauma, infection, or congenital defects. Insufficient bone density or volume poses a significant challenge, especially when planning for dental implants, which require a substantial amount of healthy bone for stability and successful osseointegration. When bone grafting is required, it’s typically because there isn’t enough native bone at a specific site to support a planned procedure or restoration. The grafting material can come from various sources: autografts (bone taken from another site in the patient’s own body, like the hip or tibia), allografts (bone from a deceased human donor, processed and sterilized), xenografts (bone from an animal source, usually bovine, also processed), or synthetic materials. The chosen material is placed into the area of bone deficiency, often mixed with the patient’s own blood or bone marrow cells to enhance healing. The graft acts as a scaffold or a biological stimulant, encouraging the body to grow new bone over several months. Procedures like Sinus Augmentation, also known as a sinus lift, are a specific type of bone grafting performed when there is insufficient bone height in the upper jaw’s back section due to the proximity of the maxillary sinus cavity. This involves adding bone graft material to the sinus floor to create enough vertical bone volume for implant placement. Bone grafting directly addresses the issue of Bone Loss and Deterioration, which can compromise the ability to chew, speak, and maintain facial structure, making it a foundational procedure for many complex dental restorations and reconstructions.

Periodontal Surgery

Periodontal surgery is a collection of surgical procedures specifically aimed at treating advanced gum disease (periodontitis) and its consequences. Periodontitis is a severe infection that damages the soft tissues and destroys the bone supporting your teeth. While early stages of gum disease can often be managed with non-surgical treatments like deep cleaning (scaling and root planing), more advanced cases where pockets have formed between the gums and teeth, or where significant bone loss has occurred, often necessitate surgical intervention. The purpose of periodontal surgery is primarily to eliminate infection, reduce pocket depth around the teeth, regenerate lost bone and tissue, and make it easier for patients to maintain oral hygiene in the future. Common types of periodontal surgery include Flap Surgery (also called pocket reduction surgery), where the gums are lifted back to allow for thorough cleaning of the tooth roots and removal of infected tissue and tartar, followed by reshaping of the bone if necessary, before stitching the gums back into place, often at a lower level to reduce pocket depth. Bone Grafting, as discussed earlier, is also a periodontal procedure used to regenerate bone that has been destroyed by periodontitis, using various grafting materials to help the body rebuild the supporting structure around teeth. Soft Tissue Grafting is performed to treat gum recession, where the gum tissue has pulled away from the tooth root, exposing the root surface. This can lead to sensitivity, root decay, and further bone loss. Soft tissue grafts, often taken from the roof of the mouth or using donor material, are used to cover the exposed root and reinforce the gum tissue. Other procedures include Gingivectomy (removal of excess gum tissue) and Gingivoplasty (reshaping healthy gum tissue) for aesthetic or functional purposes. These surgeries are usually performed by periodontists, dentists who have completed additional years of training specializing in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of periodontal disease. While they can sometimes be painful during the recovery period, these surgeries are often essential for halting the progression of gum disease, saving teeth that might otherwise be lost, and restoring the health of the supporting structures.

Understanding Tooth Extractions: Simple vs. Surgical

Tooth extraction, the removal of a tooth from its socket in the bone, might sound straightforward, but it exists on a spectrum of complexity. Not all extractions are created equal. This section is dedicated to clarifying the fundamental difference between a “simple” extraction and a “surgical” extraction, highlighting why the latter requires more advanced techniques and often involves the expertise of a surgical specialist. While both procedures achieve the same ultimate goal – removing a tooth – the approach, the tools used, and the level of difficulty involved can vary dramatically. Understanding this distinction is crucial for managing patient expectations regarding the procedure itself, the potential discomfort, and the recovery period. It helps explain why some tooth removals are quick and relatively easy, while others are more involved, requiring incisions, bone manipulation, and sutures, placing them firmly within the realm of surgical dentistry.

What is the difference between a tooth extraction and a surgical tooth extraction?

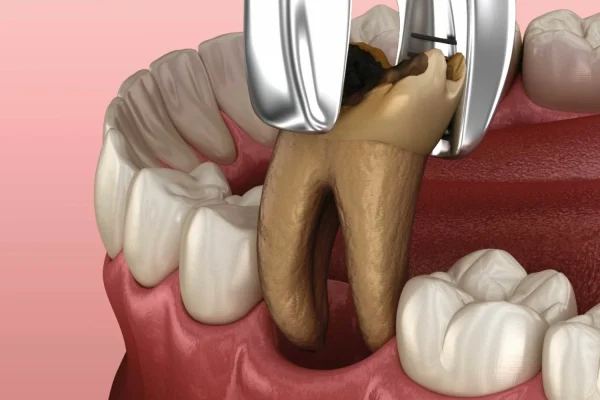

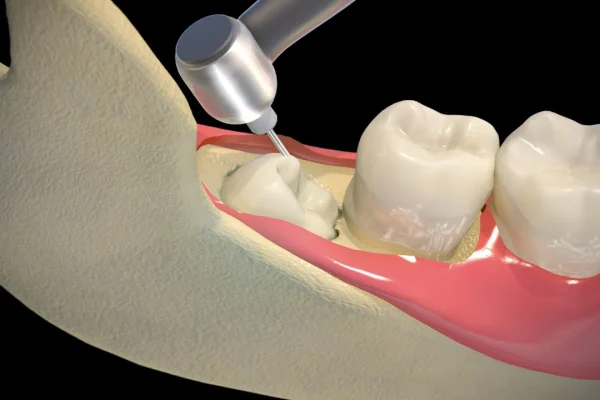

The core distinction between a standard “tooth extraction” (often referred to as a simple extraction) and a “surgical tooth extraction” lies primarily in the accessibility of the tooth and the complexity required to remove it from its socket. A Simple Dental Extraction is performed on a tooth that is fully visible in the mouth, has an intact crown, and is relatively easy to grasp with forceps. The roots are typically straightforward and not severely curved or embedded in dense bone. In this procedure, the dentist uses instruments called elevators to gently loosen the tooth from its surrounding bone and periodontal ligaments, and then forceps are used to grasp the crown and carefully remove the tooth by wiggling it back and forth to expand the socket. This type of extraction can often be performed by a general dentist under local anesthesia in a standard dental office setting. A Surgical Dental Extraction, conversely, is necessary when the tooth is not easily accessible or removable in one piece using simple elevation and forceps techniques. This is often the case for teeth that are impacted (partially or fully below the gum line or bone, like many wisdom teeth), teeth that have severely broken crowns (leaving nothing to grasp), teeth with complex or curved roots, or teeth whose roots are firmly fused to the bone (ankylosed). The procedure for a surgical extraction is more involved. It typically requires the surgeon to make an incision in the gum tissue to gain better access to the tooth and the underlying bone that might be covering it. Sometimes, a small amount of surrounding bone may need to be carefully removed with a drill or chisel to create a path for the tooth‘s removal. This step is called osteotomy or ostectomy. With the tooth exposed and any necessary bone removed, the surgeon then assesses if the tooth can be removed as a single unit. Often, particularly with multi-rooted teeth or those with curved or splayed roots, removing the tooth in one piece would require excessive force and trauma. In such cases, the surgeon will section or divide the tooth into two or more pieces using a dental drill. Each piece is then carefully loosened and removed using elevators and forceps. This sectioning allows the tooth to be extracted through a smaller opening, minimizing the amount of bone that needs to be removed and reducing trauma. After all parts of the tooth are removed, the surgeon meticulously cleans the socket, removing any debris, infected tissue, or bone fragments. Finally, the gum flap is repositioned, and sutures (stitches) are placed to close the incision and help the tissue heal properly. The type of sutures used may be dissolvable or may require removal by the dentist or surgeon a week or so later. This entire process requires significant skill, anatomical knowledge, and the use of specialized surgical instruments.

How is a tooth surgically removed?

The process of surgically removing a tooth is significantly more complex and requires a more deliberate approach than a simple extraction. It begins with administering anesthesia, typically local anesthesia around the surgical site, often combined with sedation (conscious or intravenous) to help the patient relax and feel less aware of the procedure. Once the area is completely numb and the patient is comfortable, the surgeon begins the surgical steps. The first step is usually making an incision in the gum tissue surrounding the tooth to create a flap. This flap is gently lifted to expose the tooth and the underlying bone that might be covering it. The degree of exposure needed depends on whether the tooth is partially erupted, fully impacted, or broken at the gum line. Next, if there is bone obstructing the tooth‘s removal path – common with impacted teeth like wisdom teeth – the surgeon will carefully remove a precise amount of this bone using a surgical drill and specialized burs. This step is called osteotomy or ostectomy. With the tooth exposed and any necessary bone removed, the surgeon then assesses if the tooth can be removed as a single unit. Often, particularly with multi-rooted teeth or those with curved or splayed roots, removing the tooth in one piece would require excessive force and trauma. In such cases, the surgeon will section or divide the tooth into two or more pieces using a dental drill. Each piece is then carefully loosened and removed using elevators and forceps. This sectioning allows the tooth to be extracted through a smaller opening, minimizing the amount of bone that needs to be removed and reducing trauma. After all parts of the tooth are removed, the surgeon meticulously cleans the socket, removing any debris, infected tissue, or bone fragments. Finally, the gum flap is repositioned, and sutures (stitches) are placed to close the incision and help the tissue heal properly. The type of sutures used may be dissolvable or may require removal by the dentist or surgeon a week or so later. This entire process requires significant skill, anatomical knowledge, and the use of specialized surgical instruments.

Which teeth is difficult to remove?

While any tooth extraction can present unexpected challenges, certain teeth are inherently more difficult to remove than others, particularly when surgical techniques are required. The teeth most commonly cited as challenging are the third molars, or wisdom teeth, especially when they are impacted. Impaction means the tooth is partially or fully trapped beneath the gum line or bone and cannot erupt into its proper position. The difficulty level of wisdom tooth extraction depends heavily on the degree and angle of impaction (e.g., horizontal, mesioangular, distoangular, vertical impaction) and the proximity of the roots to vital structures like the inferior alveolar nerve (which provides sensation to the lower lip and chin) and the maxillary sinus (in the upper jaw). Impacted teeth often require significant bone removal and tooth sectioning, increasing complexity. Beyond wisdom teeth, other teeth can also be difficult to remove surgically. Teeth with complex or aberrant root anatomy, such as roots that are severely curved, hooked, widely splayed, or fused together (concrescence), pose challenges as they resist the typical wiggling motion used for removal and are prone to fracturing. Teeth with roots that have become fused to the surrounding bone (ankylosis) are also very difficult, requiring extensive bone removal. Severely decayed teeth that are broken at or below the gum line offer no structure to grasp with forceps, necessitating surgical access to the root fragments embedded in the bone. Similarly, teeth that have undergone previous root canal treatment can become brittle and more likely to fracture during extraction, often requiring surgical techniques to remove the remaining pieces. Proximity to anatomical structures, like the mental nerve in the lower jaw or the sinus cavity in the upper jaw, can also increase the complexity and risk of an extraction, making it a more difficult surgical procedure requiring careful technique to avoid complications. Ultimately, the “difficulty” is a combination of the tooth‘s condition, its location, its relationship to surrounding anatomy, and the patient’s bone density and medical history.

How many teeth can be surgically removed at once?

The question of how many teeth can be surgically removed in a single appointment is a common one, and the answer isn’t a fixed number; rather, it depends on several factors, primarily the complexity of the extractions and the overall health and tolerance of the patient. For simple extractions, it’s not uncommon for a general dentist or oral surgeon to remove multiple teeth in one visit, as the procedure is less invasive per tooth. However, when discussing surgical extractions, which are inherently more complex and traumatic to the tissues, the decision to remove multiple teeth concurrently requires careful consideration. Often, especially with wisdom teeth, all four (upper and lower, left and right) are removed in a single surgical appointment. This is a very common practice, particularly for young, healthy patients, as it allows them to undergo anesthesia and a single recovery period rather than multiple ones. However, removing multiple teeth, especially complex impacted ones or those requiring significant bone removal, increases the overall duration of the procedure, the amount of anesthesia needed, and the potential for post-operative swelling, pain, and complications like bleeding or infection. For patients with underlying health conditions (like uncontrolled diabetes, bleeding disorders, or compromised immune systems), removing multiple teeth simultaneously might be deemed too risky, and the procedures may be staged over separate appointments. The complexity of the specific teeth also plays a major role; removing four relatively straightforward impacted wisdom teeth might be less taxing than removing just two teeth with severely curved, ankylosed roots requiring extensive surgery. Ultimately, the decision is a clinical judgment made by the oral surgeon in consultation with the patient, weighing the benefits of a single procedure and recovery against the potential risks and increased post-operative discomfort associated with more extensive surgery. Factors like the patient’s ability to tolerate a longer procedure, their capacity to manage post-operative care for multiple sites, and the surgeon’s preference and experience all contribute to the decision.

What is the most painful tooth to remove?

Determining the “most painful” tooth extraction is subjective, as pain perception varies greatly from person to person, but certain types of extractions are generally associated with more significant post-operative discomfort due to their inherent surgical complexity and the resulting tissue trauma. While pain during the procedure itself is effectively managed with anesthesia, it’s the post-operative recovery that patients are usually referring to when they ask about pain. Based on clinical experience and patient reports, complex surgical extractions are typically more painful during the recovery phase than simple extractions. Among these, the removal of impacted lower wisdom teeth is frequently cited as one of the most painful dental surgeries. This is because lower wisdom teeth, especially those that are fully bony impacted and angled awkwardly, often require significant surgical intervention. This involves making large incisions, removing substantial amounts of jawbone overlying the tooth, sectioning the tooth into multiple pieces, and considerable manipulation to get the pieces out. This process causes more trauma to the surrounding bone, gums, and potentially nearby nerves and muscles compared to removing a visible tooth. The inflammatory response to this level of surgical manipulation leads to greater swelling, bruising, and pain in the days following the procedure. Other surgical extractions that can be particularly painful during recovery include the removal of multi-rooted back teeth that are severely decayed or broken below the gum line, requiring extensive surgical retrieval of root fragments, or the removal of teeth that are fused to the bone (ankylosed), necessitating significant bone removal. While pain is an expected part of healing from these procedures, modern pain management strategies, including prescribed pain medication (both opioids and non-opioids), anti-inflammatory drugs, and applying ice packs, are highly effective in controlling discomfort and making the recovery process much more manageable than it might have been in the past.

Is a Root Canal Considered Surgical Dental?

The classification of a root canal procedure within the realm of surgical dentistry is a point of frequent confusion. While it is an invasive procedure performed within the tooth structure, involving specialized tools to access and clean out infected tissue, a standard root canal is typically not categorized as oral or surgical dentistry in the same way that extracting an impacted tooth or placing a dental implant is. To address this specific question, let’s clarify the nature of a root canal and its relationship to surgical procedures.

Is a root canal surgery?

A standard root canal procedure, also known as endodontic therapy, is not typically classified as oral surgery or surgical dentistry. It is an invasive procedure performed by a general dentist or, more commonly, an endodontist (a specialist in the diseases of the dental pulp and tooth root), but it operates within a different specialty domain than oral surgery. The purpose of a root canal is to treat infection or inflammation within the pulp chamber and root canals of a tooth – the innermost part containing nerves, blood vessels, and connective tissue. The procedure involves accessing the pulp chamber through the tooth‘s crown, removing the infected or damaged pulp tissue from the root canals, cleaning and shaping the canals, and then filling and sealing them to prevent future infection. While it uses instruments to enter the tooth and manipulate internal tissues, it does not typically involve incisions in the gums, removal of bone surrounding the tooth (except sometimes minimal access preparation through bone), or the surgical techniques associated with accessing impacted structures or manipulating the jawbone itself. The procedure is performed entirely within the tooth structure. However, there is one specific procedure related to root canals that is considered oral surgery: an apicoectomy. An apicoectomy, or root-end resection, is a surgical procedure performed when an infection persists at the tip of a tooth‘s root after a standard root canal has been completed. This involves the oral surgeon (or endodontist trained in surgical endodontics) making an incision in the gum tissue near the affected tooth, accessing the bone overlying the root tip, surgically removing the very end of the root, cleaning out the infected tissue around it, and sealing the end of the root with a small filling. This procedure is performed outside the tooth structure, in the bone and gum tissue, using surgical techniques, thus classifying it as a surgical procedure. So, while a routine root canal is not surgery, a surgical extension of root canal treatment, like an apicoectomy, is. This distinction is important for understanding the different scopes of practice within dental specialties; endodontists are experts in the internal anatomy and treatment of teeth, while oral surgeons specialize in the surrounding bone and soft tissues and more complex structural interventions.

Addressing Concerns: Is Surgical Dental Painful?

A natural and very common concern for anyone facing surgical dental work is the potential for pain. The word “surgery” itself can conjure images of discomfort. It’s important to address this head-on and provide realistic expectations while also reassuring patients about modern pain management techniques. The reality is that while some discomfort is expected during the recovery period from most surgical procedures, severe or uncontrolled pain is not the norm thanks to advancements in anesthesia and post-operative care. This section aims to clarify what patients can expect regarding pain before, during, and after oral surgery, distinguishing between different procedures and emphasizing the strategies used to minimize discomfort.

Is oral surgery painful?

During the actual oral surgery procedure, patients should not experience pain. Modern anesthesia techniques are highly effective in preventing pain during the intervention itself. The type of anesthesia used depends on the complexity of the procedure, the patient’s health, and their anxiety level. Local anesthesia is always used to numb the surgical site, blocking pain signals from reaching the brain. For more involved procedures or anxious patients, local anesthesia is often combined with sedation (conscious or IV sedation) which puts the patient in a relaxed, semi-awake state where they are less aware of what is happening and often have little memory of the procedure. For complex or lengthy surgeries, general anesthesia may be administered, rendering the patient completely unconscious and unable to feel pain. Therefore, while you might feel pressure or movement, you should not feel sharp pain during the surgery if the anesthesia is effective. The pain associated with oral surgery primarily occurs after the anesthesia wears off, during the recovery period. The degree of post-operative pain varies significantly depending on the invasiveness and complexity of the surgery performed. Simple surgical extractions might result in moderate discomfort for a few days, while more extensive procedures like multiple impacted wisdom tooth removals, bone grafting, or corrective jaw surgery will typically lead to more significant pain, swelling, and bruising that can last for a week or longer. However, this post-operative pain is manageable with prescription and/or over-the-counter pain medications provided or recommended by the surgeon. The surgeon will develop a pain management plan tailored to the specific procedure and patient, aiming to keep discomfort at a tolerable level throughout the healing process. So, while it’s not accurate to say oral surgery is completely painless overall, the pain is primarily limited to the recovery phase and is effectively controlled with medication.

How painful is surgical extraction?

Compared to a simple tooth extraction, a surgical extraction is generally associated with more post-operative pain. A simple extraction typically results in minimal discomfort, often manageable with over-the-counter pain relievers like ibuprofen or acetaminophen for a day or two. A surgical extraction, however, involves more significant manipulation of tissues, bone, and the tooth itself. As described earlier, this often includes making incisions, lifting gum flaps, potentially removing bone, sectioning the tooth, and placing sutures. This increased level of invasiveness naturally leads to a greater inflammatory response as the body begins to heal. Patients undergoing surgical extractions can expect moderate to sometimes severe pain in the first 24-72 hours following the procedure. This pain is usually localized to the extraction site but can radiate to the jaw, ear, or head. Swelling and bruising are also common accompanying symptoms that contribute to the discomfort. The severity of the pain is highly dependent on the complexity of the specific extraction. For example, removing a fully bony impacted lower wisdom tooth, especially if it’s deeply embedded or close to a nerve, is typically more painful during recovery than surgically removing a partially erupted tooth. Factors like the patient’s individual pain tolerance, how well they follow post-operative instructions (such as using ice packs and taking medications on schedule), and their overall health status also play a role. However, while the pain from a surgical extraction can be more intense than that from a simple extraction, it is usually predictable and effectively managed with the pain medications prescribed by the oral surgeon. These often include prescription-strength anti-inflammatory drugs and/or opioid painkillers for the initial few days, transitioning to over-the-counter options as the pain subsides. The pain should steadily improve after the first few days; if it worsens significantly or is accompanied by signs of infection (fever, increasing swelling, foul taste), it’s crucial to contact the surgeon’s office.

What is the most painful dental surgery?

Pinpointing the absolute single “most painful” dental surgery is difficult because pain is subjective and varies greatly between individuals. However, certain procedures are consistently reported as causing more significant post-operative discomfort than others due to their extensive nature and the amount of tissue manipulation involved. Procedures that involve significant bone removal, manipulation of large areas, or affect multiple anatomical structures tend to be higher on the pain scale during recovery. Complex Corrective Jaw Surgery (Orthognathic Surgery), especially involving both the upper and lower jaws, is often cited as one of the most significant dental surgeries in terms of pain, swelling, and recovery duration. This surgery involves cutting and repositioning large segments of bone, leading to widespread facial swelling, bruising, and considerable discomfort managed with strong pain relief during a hospital stay. Extensive bone grafting procedures, particularly those involving harvesting bone from other parts of the body (like the hip or tibia) in addition to the oral surgery site, can also be very painful, as the patient experiences pain at both the donor site and the recipient site. Similarly, complex removal of deeply impacted teeth, especially those near major nerves or requiring significant bone reshaping, can lead to intense localized pain and swelling. While not always the “most” painful, complications like “dry socket” (alveolar osteitis) following an extraction, which occurs when the blood clot in the socket dislodges, can cause excruciating pain that is often described as worse than the initial surgery itself, though this is a complication rather than the surgery itself. Procedures involving extensive manipulation of infected or inflamed tissues might also be particularly uncomfortable during healing. Ultimately, the perception of pain is influenced by factors like the surgeon’s skill, the patient’s health and pain tolerance, and the effectiveness of the pain management plan. However, procedures that cause the most widespread tissue and bone trauma generally lead to the highest levels of post-operative pain.

Is teeth surgery very painful?

While the term “teeth surgery” can encompass a range of procedures with varying levels of discomfort, it’s generally inaccurate to say that all teeth surgery is “very painful” in an uncontrolled sense. Thanks to modern anesthesia, patients experience no pain during the procedure itself. The pain occurs after the surgery, during the healing phase, and the intensity varies significantly depending on the specific procedure performed. For a simple extraction (sometimes loosely called “teeth surgery“), post-operative pain is usually mild and short-lived. Even for many surgical extractions, while more painful than simple ones, the discomfort is typically moderate and peaks within the first 1-3 days, then steadily improves. It’s the more complex interventions, such as multiple impacted wisdom tooth removals, extensive bone grafting, or major jaw surgeries, that are associated with more significant post-operative pain and swelling. However, even in these cases, while discomfort is substantial, it is usually manageable with the pain medication prescribed by the surgeon. The goal of post-operative care and pain management is not necessarily to eliminate pain entirely, which is often unrealistic during tissue healing, but to reduce it to a tolerable level that allows the patient to recover comfortably. Proper pain management involves taking prescribed medications on schedule, using ice packs to reduce swelling, resting, and avoiding activities that could aggravate the surgical site. While the prospect of any surgery can be intimidating due to the fear of pain, patients can be reassured that modern surgical techniques and pain control strategies are designed to minimize suffering. If a patient experiences pain that is severe and not controlled by medication, or that worsens unexpectedly after the first few days, it’s essential to contact their oral surgeon, as this could be a sign of a complication like infection or dry socket requiring further attention.

Navigating the Risks and Safety of Surgical Dental

Undergoing any surgical procedure, no matter how routine, carries a degree of risk. Surgical dentistry is no exception. While these procedures are performed by highly trained professionals and are generally very safe, it’s crucial for patients to be aware of potential risks and complications. A well-informed patient is better prepared for the recovery process and knows what to look for that might require contacting their surgeon. This section addresses common questions about the safety of dental surgery and outlines the typical risks involved, while also highlighting the best practices employed by practitioners to minimize these potential issues and ensure patient safety.

Is dental surgery high risk?

The assessment of whether dental surgery is “high risk” is relative and depends heavily on the specific procedure being performed, the patient’s overall health status, and the skill of the practitioner. For the majority of routine surgical dental procedures performed by qualified oral surgeons or experienced general dentists, such as straightforward surgical extractions or simple implant placements in healthy patients, the risk profile is generally considered low to moderate. Major complications are relatively uncommon. These procedures are performed frequently, utilize established protocols, and are typically completed on an outpatient basis under controlled conditions. However, the risk level can increase with the complexity of the surgery. Procedures like extensive corrective jaw surgery, reconstruction following major trauma or cancer treatment, or surgeries performed on medically compromised patients (those with significant heart conditions, uncontrolled diabetes, or weakened immune systems) inherently carry higher risks, similar to other major surgical interventions in different parts of the body. These procedures often require general anesthesia administered by an anesthesiologist, a hospital setting, and involve more extensive tissue manipulation and potential blood loss. The specific risks also vary by procedure; for example, nerve injury is a particular concern with lower jaw surgery or wisdom tooth extraction, while sinus perforation is a risk with upper jaw surgery or implant placement in the posterior maxilla. However, it’s crucial to emphasize that oral and maxillofacial surgeons are specifically trained to identify, minimize, and manage these potential risks. They conduct thorough pre-operative assessments, utilize advanced imaging for precise planning, employ sterile techniques to prevent infection, and have protocols in place to manage complications should they arise. While no surgery is entirely risk-free, characterizing all dental surgery as “high risk” would be misleading; many common procedures are very safe, though informed consent requires discussing all potential outcomes, including less common complications.

Is dental surgery safe?

Yes, in the vast majority of cases, modern dental surgery performed by qualified professionals is considered very safe. Several factors contribute to this high safety profile. Firstly, the field has benefited immensely from advancements in anesthesia techniques, making procedures painless and comfortable for patients while allowing for careful monitoring of vital signs. Whether it’s local anesthesia, sedation, or general anesthesia, these methods are refined and administered with a focus on patient safety. Secondly, surgical techniques themselves have evolved significantly. Procedures are often less invasive than in the past, utilizing precision instruments and advanced imaging (like 3D cone-beam CT scans) for meticulous pre-operative planning. This allows surgeons to visualize the anatomy in three dimensions, identify the exact location of nerves, blood vessels, and sinus cavities, and plan the most efficient and least traumatic surgical approach. This meticulous planning is key to minimizing operative time and reducing the risk of complications. Thirdly, strict adherence to sterilization protocols and infection control measures in dental offices and surgical centers is paramount. These practices, often guided by recommendations from bodies like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), drastically reduce the risk of post-operative infection, which was historically a more significant concern. Furthermore, the training received by oral and maxillofacial surgeons is rigorous and extensive, including significant hospital-based experience where they learn to manage medical emergencies and complex surgical scenarios. This level of expertise is a major factor in ensuring patient safety. While complications can occasionally occur, they are generally rare, and oral surgeons are trained to recognize and manage them effectively. Choosing a board-certified oral and maxillofacial surgeon or an experienced general dentist for appropriate procedures, coupled with a thorough pre-operative assessment of the patient’s health, significantly enhances the safety of dental surgery. Patients should always feel comfortable discussing any concerns they have about risks and safety with their surgeon before undergoing a procedure.

What are the risks or complications of oral surgery?

While oral surgery is generally safe, like any surgical procedure, it carries potential risks and complications. Being aware of these possibilities is part of the informed consent process and helps patients understand what to monitor during recovery. The most common risks include pain, swelling, and bruising, which are considered expected consequences of surgery and are managed with medication and self-care. Beyond these expected outcomes, other potential complications, though less frequent, include:

- Infection: Any surgical site is susceptible to bacterial infection. This risk is minimized through sterile technique during the procedure, proper post-operative oral hygiene (often including prescribed antibiotics or rinses), and meticulous cleaning of the site. Signs of infection can include increasing pain after the first few days, persistent swelling, fever, pus, or a foul taste/smell.

- Bleeding: Some bleeding is normal after surgery, but excessive or prolonged bleeding (beyond 24 hours or not controlled by pressure) can occur. This is more likely in patients with bleeding disorders or those taking anticoagulant medications. The surgeon provides instructions on how to manage minor bleeding and when to seek help for persistent bleeding.

- Nerve Injury: This is a specific risk in procedures involving the lower jaw, particularly wisdom tooth removal or implant placement in the posterior mandible, due to the proximity of the inferior alveolar nerve (providing sensation to the lower lip, chin, and teeth) and the lingual nerve (providing sensation and taste to the tongue). Injury can result in temporary or, in rare cases, permanent numbness or altered sensation in the lip, chin, or tongue. Surgeons take precautions like using advanced imaging and careful technique to avoid nerve damage.

- Dry Socket (Alveolar Osteitis): This painful condition can occur after tooth extraction when the blood clot that forms in the socket dislodges or dissolves prematurely, exposing the underlying bone and nerves. It causes intense, throbbing pain, often radiating to the ear, and typically occurs a few days after the extraction. It is treated by cleaning and dressing the socket to protect the exposed bone. Smoking significantly increases the risk of dry socket.

- Damage to Adjacent Teeth or Structures: During extraction or other procedures, there is a small risk of inadvertently damaging neighboring teeth, fillings, crowns, or bony structures not involved in the main surgery.

- Sinus Complications: In procedures involving the upper jaw, particularly in the posterior region (like upper wisdom tooth extraction or sinus lifts), there is a risk of perforating the maxillary sinus cavity. Small perforations often heal on their own, but larger ones may require surgical repair to prevent chronic sinus issues.

- Reaction to Anesthesia: Although rare, adverse reactions to local anesthetics, sedatives, or general anesthesia can occur. This highlights the importance of providing a complete medical history to the surgeon and anesthesiologist.

- Delayed Healing or Failure of the Procedure: Healing may take longer than expected, or in the case of implants or bone grafts, the procedure may partially or completely fail, requiring further treatment or removal of the implant/graft.

These are potential risks, and while they can happen, serious complications are not common. Surgeons discuss these possibilities during the consultation to ensure informed consent and provide guidance on how to minimize them.

Best Practices for Oral Surgical Procedures

Ensuring the safety and success of oral surgical procedures is paramount, and this is achieved through strict adherence to established best practices by the surgical team. These practices encompass everything from patient assessment and sterile technique to surgical planning and post-operative care. One of the most fundamental best practices is a thorough pre-operative evaluation of the patient. This includes a detailed review of their medical history, current medications (especially blood thinners, bisphosphonates, or immunosuppressants), allergies, and any systemic health conditions that could affect surgery or healing, such as diabetes, heart disease, or autoimmune disorders. This assessment is crucial for identifying potential risks and modifying the surgical plan or requiring medical clearance from other physicians if necessary. Best Practices for Oral Surgical Procedures | Dental Infection Prevention and Control | CDC guidelines, for instance, emphasize the critical importance of infection control. This includes strict adherence to sterile protocols: using properly sterilized instruments and equipment, surgical staff wearing appropriate sterile gowns, masks, gloves, and eyewear, and preparing the surgical site with antiseptic solutions. Maintaining a sterile field throughout the procedure is non-negotiable to prevent microbial contamination and post-operative infection. Precise surgical planning, often aided by advanced imaging technologies like cone-beam CT scans, allows surgeons to visualize the anatomy in three dimensions, identify the exact location of nerves, blood vessels, and sinus cavities, and plan the most efficient and least traumatic surgical approach. This meticulous planning is key to minimizing operative time and reducing the risk of complications. During the procedure, surgeons employ gentle tissue handling techniques to minimize trauma, which promotes faster and less complicated healing. Hemostasis (controlling bleeding) is actively managed throughout the surgery. Finally, clear and comprehensive post-operative instructions are a critical best practice. Patients must be fully informed about expected discomfort, how to manage pain and swelling, instructions for oral hygiene, dietary restrictions, signs and symptoms of potential complications, and when and how to contact the surgeon. Follow-up appointments are scheduled to monitor healing and address any concerns. Adherence to these and other clinical guidelines ensures that oral surgical procedures are performed as safely and effectively as possible, prioritizing patient well-being and optimal outcomes.

Preparing For and Recovering From Surgical Dental

Undergoing surgical dental work involves more than just the time spent in the surgical chair; it requires preparation beforehand and careful management during the recovery period to ensure a smooth healing process and optimal results. Knowing what to do before your appointment and what to expect as you recover can significantly reduce anxiety and improve the outcome. This section provides essential guidance on how to prepare yourself for oral surgery and navigate the post-operative phase, covering everything from practical tips to key aspects of aftercare. Being well-informed about these stages empowers patients to actively participate in their healing journey.

How to Prepare for Oral Surgery

Proper preparation for oral surgery is essential for a successful procedure and a smoother recovery. The process begins after your consultation with the surgeon and receiving your specific instructions. How to Prepare for Oral Surgery | Cigna Healthcare and similar resources offer valuable guidance. Firstly, ensure you fully understand the procedure, why it’s necessary, and any alternative treatment options. Don’t hesitate to ask your surgeon questions during the consultation about the surgery itself, the anesthesia, potential risks, and the expected recovery. Secondly, discuss your complete medical history and all medications, supplements, and over-the-counter drugs you are taking with your surgeon. Some medications, like blood thinners, may need to be adjusted or temporarily stopped before surgery, but only under the strict guidance of the prescribing physician and your surgeon. Inform your surgeon about any allergies, particularly to medications like antibiotics or anesthetic agents. Follow pre-operative fasting instructions precisely if sedation or general anesthesia is planned; typically, this involves not eating or drinking anything for a specific number of hours before the appointment. This is crucial to prevent complications related to anesthesia. Arrange for a responsible adult to drive you home after the surgery if you are receiving sedation or general anesthesia, as you will not be able to drive yourself. Wear comfortable, loose-fitting clothing on the day of your appointment. Avoid wearing makeup or jewelry near the surgical site. If you wear contact lenses, you may be asked to remove them. Ensure you have a supply of soft foods and liquids at home, as your diet will be restricted initially. Fill any prescriptions for pain medication, antibiotics, or special rinses before your appointment so you have them ready immediately after surgery. Prepare your recovery space at home with pillows to prop your head up, ice packs, and entertainment. Having everything ready in advance reduces stress and makes the initial recovery hours much easier. Being organized and following your surgeon’s specific instructions are key steps in preparing yourself effectively for oral surgery.

What to expect when getting an oral surgery?

Knowing what to expect can significantly reduce anxiety on the day of your oral surgery. When you arrive at the clinic or hospital, you will check in and likely spend some time in a waiting area. You will then be called back to a pre-operative area where a nurse or assistant will take your vital signs and review your medical history and the planned procedure. You might be asked to change into a surgical gown. If you are receiving sedation or general anesthesia, the anesthesiologist or surgical assistant will prepare you and administer the medication. As the anesthesia takes effect, you will feel yourself becoming relaxed or falling asleep, depending on the type used. During the procedure itself, if you are awake with local anesthesia, you will feel pressure, vibrations, and hear sounds from the instruments, but you should not feel sharp pain. If you are sedated, you will be very drowsy and likely won’t remember much of the procedure. Under general anesthesia, you will be completely unconscious. The surgical team works efficiently to complete the procedure according to the plan. Once the surgery is finished, you will be moved to a recovery area. If you had local anesthesia only, recovery is usually brief. If you had sedation or general anesthesia, you will remain in the recovery area until you are fully awake and your vital signs are stable. You may feel groggy, dizzy, or nauseous initially. The surgical site will likely be numb from the local anesthetic, but this will wear off over the next few hours. Before you are discharged, the surgical team will provide you and your escort with detailed post-operative instructions, prescriptions, and an opportunity to ask any final questions. You should expect some discomfort, swelling, and potentially bruising to develop in the hours following surgery as the anesthetic wears off. The immediate post-operative period involves managing these expected symptoms and beginning the healing process at home.

Recovery and Aftercare

Recovery and Aftercare from oral surgery is a process that requires patience and diligent adherence to post-operative instructions to ensure proper healing and minimize the risk of complications. The initial recovery period, typically the first 24-72 hours, is usually the most uncomfortable. During this time, swelling and pain are most pronounced. Recovery and Aftercare involve several key components. Pain management is crucial; take prescribed pain medication as directed by your surgeon before the local anesthetic wears off completely and stay ahead of the pain. Over-the-counter options like ibuprofen or acetaminophen may also be recommended or used in conjunction with prescription medication. Swelling control is another major aspect; apply ice packs to the outside of your face over the surgical area for 15-20 minutes on and off during the first 24-48 hours. Keeping your head elevated, even while sleeping, can also help reduce swelling. A restricted diet is necessary initially to avoid disturbing the surgical site. Start with liquids immediately after surgery (once you are fully alert and the bleeding is controlled), progressing to soft foods like yogurt, mashed potatoes, soup, and smoothies as tolerated over the next few days. Avoid hot liquids, hard, crunchy, or sharp foods, and definitely no straws, as the sucking motion can dislodge the blood clot in extraction sites (causing dry socket). Gentle oral hygiene is important to keep the area clean and prevent infection. Your surgeon will advise you on when and how to start rinsing (usually gentle salt water rinses starting 24 hours after surgery) and brushing your teeth, often recommending avoiding the surgical site initially. Rest is vital for healing; avoid strenuous activity, heavy lifting, or vigorous exercise for at least several days, or as advised by your surgeon. Smoking and alcohol consumption should be avoided as they can significantly impair healing. Monitor the surgical site for signs of complications, such as excessive bleeding, increasing pain or swelling after the first few days, fever, or pus, and contact your surgeon if any concerning symptoms arise. Follow-up appointments are typically scheduled to check healing progress and remove sutures if necessary. Adhering to these guidelines is fundamental to a smooth and successful recovery.

What is the recovery time?

The recovery time following oral surgery varies considerably depending on the specific procedure performed and the individual patient’s healing ability. There isn’t a single answer that applies to all cases of “surgical dental.” For relatively minor surgical extractions, like a single non-impacted tooth requiring sectioning, the acute recovery period (when pain and swelling are most significant) might last just 3 to 5 days, with most patients feeling significantly better within a week and able to return to normal activities. However, full tissue healing takes longer. For more complex procedures, such as the surgical removal of multiple impacted wisdom teeth or bone grafting, the initial recovery with noticeable swelling, bruising, and moderate pain might last 7 to 10 days. During this time, patients often need to restrict their diet and activities. Significant bruising can sometimes take up to two weeks to completely resolve. Procedures like dental implant placement often have a shorter acute recovery period (a few days of discomfort and swelling), but the osseointegration process, where the bone fuses to the implant, takes several months (typically 3 to 6 months) before the final crown can be placed. Corrective jaw surgery involves the longest recovery; patients typically spend a few days in the hospital, experience significant swelling and discomfort for several weeks, and require a liquid or soft food diet for an extended period. Full functional recovery and resolution of swelling can take several months to a year. Periodontal surgery recovery depends on the extent of the procedure but often involves noticeable discomfort for a week or two, with complete gum healing taking longer. Generally, while the most intense discomfort and swelling subside within the first week or two for most outpatient procedures, complete healing of the bone and soft tissues takes weeks to months. Your oral surgeon will provide you with a more specific estimate of the expected recovery timeline based on your individual procedure and circumstances. Patience and following their instructions throughout the entire healing period are crucial for the best outcome.

What are some important aspects of oral surgery recovery?