Table of Contents

ToggleKey Takeaways

- Orthodontia is a specialized branch of dentistry focused on diagnosing, preventing, and correcting improperly positioned teeth and jaws (malocclusion).

- The primary goals of orthodontia include improving oral health, enhancing dental function (such as chewing and speaking), and creating a more aesthetically pleasing smile.

- Common treatments include traditional braces, ceramic braces, lingual braces, clear aligners like Invisalign, and crucial follow-up care with retainers.

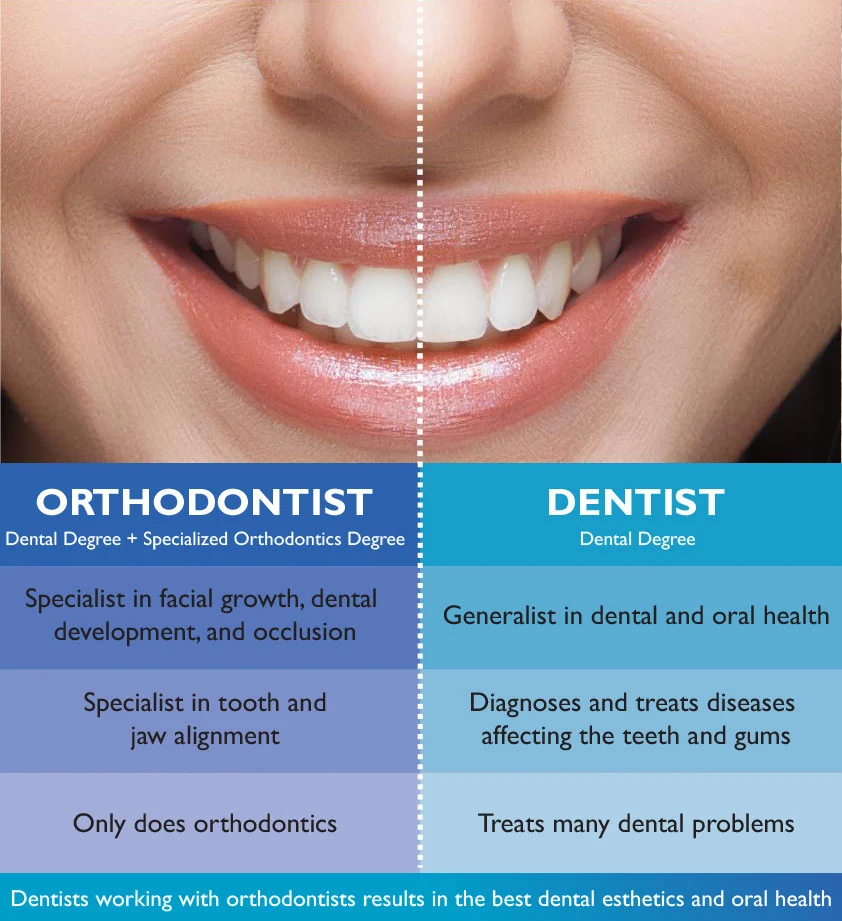

- An orthodontist is a dental specialist who has completed an additional two to three years of full-time postgraduate training in orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics after dental school.

- While “orthodontia” and “orthodontics” are often used interchangeably by the public, “orthodontics” is the more formal term referring to the dental specialty itself.

- Key advantages include easier oral hygiene, reduced risk of tooth decay and gum disease, alleviation of jaw joint pain, improved bite function, and a significant boost in self-confidence.

What is a Orthodontia, Fundamentally? Exploring the Core Definition

Alright, let’s get to the heart of it. Before we dive into the nuances of treatments like braces or clear aligners, or distinguish orthodontia from other dental procedures, we need a rock-solid understanding of what the term fundamentally represents. At its core, orthodontia is a specialized discipline within the broader field of dentistry. Its primary mission, stated simply, is the diagnosis, prevention, interception, and correction of malpositioned teeth and jaws, often referred to as “malocclusion” or simply a “bad bite.” It’s about achieving harmony between the teeth, the jaws, and the facial muscles. Think of it less as cosmetic tinkering and more as resolving structural issues that have profound implications for oral health and function. While a straighter smile is often the most visible outcome, the underlying goals are frequently rooted in improving how you bite, chew, and even speak, while also making your teeth easier to clean, thereby reducing the risk of future dental problems like decay and gum disease. It’s a proactive and corrective field, meticulously planning and executing tooth movements and sometimes influencing jaw growth to create a stable, healthy, and aesthetically pleasing result. Understanding this foundational purpose is key to appreciating the scope and significance of the treatments involved, moving beyond surface-level perceptions to grasp the genuine health benefits it delivers. Many people use “orthodontia” and “orthodontics” without distinction, and for most practical purposes, they refer to the same specialty. However, delving into the specific meanings and origins helps paint a fuller picture of this dental domain and its evolution over time, setting the stage for understanding its specific applications and the experts who practice it.

What Does the Term “Orthodontia” Specifically Mean?

Let’s break down the word itself, as etymology often holds the key to meaning. “Orthodontia” traces its roots back to Greek. “Orthos” translates to “straight” or “correct,” and “odous” (or “odont”) means “tooth.” Put them together, and you essentially get “straight tooth.” This origin beautifully encapsulates the primary, most visible goal of the specialty: achieving properly aligned teeth. However, the scope is broader than just individual teeth; it inherently involves the relationship between the teeth, how they fit together (occlusion), and their connection to the jawbones and facial structure. Orthodontia, therefore, is the branch of dentistry concerned specifically with correcting dental irregularities – think crooked teeth, crowded teeth, gaps, and improper bites. While the term “orthodontics” is now more prevalent in professional circles and contemporary usage, “orthodontia” remains perfectly valid and is often encountered, particularly in older dental literature, formal definitions, or sometimes even in insurance terminology. It emphasizes the outcome – the state of having corrected teeth and jaws. It’s less about the “-ics” suffix implying a field of study, and more about the condition and the treatment thereof. Understanding “orthodontia” through its etymological lens reinforces its core focus: the art and science of moving teeth and aligning jaws into their most functionally sound and aesthetically harmonious positions, ensuring not just a pretty smile, but one that works correctly and supports overall oral health for the long haul. It’s the foundational concept upon which the entire specialty is built.

And What About “Orthodontics”? Understanding its Meaning

So, if “orthodontia” means “straight tooth,” what about “orthodontics”? The difference lies largely in that “-ics” suffix. In English, “-ics” often denotes a field of study, a science, or a practice (like physics, economics, or athletics). Therefore, “orthodontics” is the more formal and widely accepted term for the dental specialty itself – the science and practice dedicated to preventing, diagnosing, and treating dental and facial irregularities. It encompasses the entire body of knowledge, the diagnostic techniques, the treatment planning strategies, the various appliances used (braces, aligners, retainers, etc.), and the ongoing research within the field. While “orthodontia” might subtly emphasize the treatment or the condition, “orthodontics” clearly defines the professional discipline. Think of it this way: a patient undergoes orthodontia (the treatment process) performed by a specialist practicing orthodontics. Most dental schools, professional organizations (like the American Association of Orthodontists), and practitioners today refer to the field as orthodontics. It’s the term you’ll see on a specialist’s diploma and woven throughout modern dental communication. Functionally, however, when discussing the general concept of straightening teeth and correcting bites with patients or in public health information, the terms are often used interchangeably without causing confusion. Both point to the same essential goal: creating healthy, functional, and aesthetically pleasing alignment of the teeth and jaws. Recognizing “orthodontics” as the name of the specialty helps contextualize the advanced training and expertise required to practice in this area effectively and safely. It signifies a dedicated focus beyond general dentistry.

How Do Authoritative Sources Define Orthodontia? Insights from MedlinePlus, Wikipedia, and Dictionaries

To truly solidify our understanding, let’s consult some trusted external sources. How do established medical and general knowledge platforms define orthodontia or orthodontics? MedlinePlus, a reputable service of the U.S. National Library of Medicine, typically frames orthodontics within a health context, describing it as the dental specialty focused on correcting teeth and jaws that are positioned improperly. It often highlights the health benefits, such as reducing the risk of tooth decay and periodontal disease, relieving stress on chewing muscles, and addressing jaw joint issues. Wikipedia, in its extensive article on Orthodontics, defines it as a specialty field of dentistry dealing with diagnosis, prevention, and correction of malpositioned teeth and jaws. It delves into the history, treatment modalities (like braces and aligners), the concept of dentofacial orthopedics (guiding facial growth), and the required training for specialists. It underscores the interchangeability of the terms while predominantly using “orthodontics.” Turning to dictionaries, Merriam-Webster defines “orthodontia” as “a branch of dentistry dealing with irregularities of the teeth (such as malocclusion) and their correction (as by braces).” Dictionary.com offers a similar definition: “the branch of dentistry dealing with the prevention and correction of irregular teeth, as by means of braces.” These definitions consistently emphasize two core components: the problem (irregular teeth, malocclusion, misaligned jaws) and the solution (correction, prevention, treatment, often mentioning braces as a key tool). Consulting these diverse yet converging sources reinforces that orthodontia/orthodontics is a well-established, crucial dental specialty focused squarely on alignment and bite correction for both health and aesthetic reasons, recognized universally by medical, encyclopedic, and linguistic authorities.

What is an Orthodontist and What is Their Role in Orthodontia?

Now that we’ve defined the field, let’s talk about the expert: the orthodontist. An orthodontist is not just any dentist. They are a dental specialist who has dedicated several additional years of full-time, post-doctoral training exclusively in orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics after completing dental school. Think of it like the difference between a general medical practitioner and a cardiologist; both are doctors, but the cardiologist has specialized expertise in the heart. Similarly, an orthodontist possesses advanced knowledge and skills specifically focused on tooth movement, jaw growth, bite correction, and facial aesthetics. Their role within orthodontia is paramount. They are the diagnosticians who meticulously analyze a patient’s teeth, jaws, and facial structure using tools like X-rays, photos, and dental impressions or digital scans. They develop comprehensive treatment plans tailored to each individual’s unique needs and goals. They are the practitioners who expertly place and manage orthodontic appliances – whether traditional braces, ceramic braces, lingual braces, or clear aligners like Invisalign – guiding the teeth and jaws into their optimal positions over time. Furthermore, orthodontists manage the crucial retention phase after active treatment, prescribing and monitoring retainers to ensure the beautiful results achieved are stable long-term. They treat patients of all ages, from children needing early interceptive treatment to guide jaw growth, to adolescents undergoing comprehensive correction, to adults seeking to improve their smile and oral health later in life. Their expertise extends beyond simply straightening visible teeth; it encompasses creating a harmonious bite, improving jaw function, and enhancing overall facial balance, making them the definitive authority in the field of orthodontia.

Why is Orthodontics Used and What Are Its Key Advantages?

Moving beyond definitions, let’s explore the why. Why do people embark on the journey of orthodontic treatment? While the allure of a perfectly straight, camera-ready smile is undeniably a powerful motivator for many, the reasons for using orthodontics, and its resulting advantages, run much deeper than mere vanity. This specialty addresses fundamental issues related to oral health, function, and even psychological well-being. Malocclusion, or a “bad bite,” isn’t just an aesthetic concern; it can lead to a cascade of tangible problems, from difficulty chewing properly to excessive wear on certain teeth, and even contribute to jaw joint pain (TMJ/TMD). Furthermore, crowded or crooked teeth are notoriously harder to keep clean, creating pockets where plaque and bacteria can flourish, significantly increasing the risk of cavities and gum disease – the leading cause of tooth loss in adults. Therefore, pursuing orthodontic treatment is often a strategic investment in long-term oral health. The advantages are twofold, encompassing both significant improvements in the physical health and functionality of the mouth, and considerable boosts in confidence and self-esteem stemming from an improved appearance. Understanding this dual nature of orthodontic benefits – the tangible health improvements and the intangible psychological uplift – is crucial for appreciating its true value. It’s not just about looking better; it’s about living healthier and feeling more confident in one’s own skin, making it a profoundly impactful area of healthcare.

What is the Primary Purpose of Pursuing Orthodontic Treatment?

The fundamental, primary purpose driving orthodontic treatment is the correction of malocclusion – that clinical term for teeth that don’t fit together correctly. This encompasses a wide array of issues: teeth that are overcrowded, crooked, or spaced too far apart; jaws that are misaligned, leading to overbites (where the upper front teeth excessively overlap the lower ones), underbites (lower teeth protruding past upper teeth), crossbites (upper teeth biting inside lower teeth), or open bites (a gap between upper and lower teeth when biting). The goal is to establish a healthy, functional occlusion, meaning a bite where the teeth meet properly, distributing chewing forces evenly and allowing for efficient function without undue stress on individual teeth or the jaw joints. Beyond just tooth alignment, a crucial aspect, especially in younger, growing patients, is guiding facial development. This falls under the umbrella of dentofacial orthopedics, often practiced concurrently by orthodontists. By intervening at the right time, orthodontists can influence the growth of the jaws to achieve better balance and proportion, potentially preventing more complex issues or the need for jaw surgery later in life. Therefore, the primary purpose is profoundly functional and developmental: to create a bite that works efficiently, supports long-term oral health by making cleaning easier and reducing wear, and harmonizes with the patient’s overall facial structure. While aesthetic improvement is a highly valued outcome, it stems directly from achieving these core functional and developmental objectives.

What Are the Significant Benefits You Can Expect From Orthodontia?

The advantages of undergoing orthodontic treatment extend far beyond the mirror. While achieving a beautiful, straight smile is certainly a major plus, the significant benefits are multifaceted. Firstly, oral hygiene dramatically improves. Straight teeth are simply easier to brush and floss effectively compared to crowded or overlapping teeth. This enhanced cleanability directly translates into a reduced risk of developing tooth decay (cavities) and periodontal (gum) disease, safeguarding your natural teeth for longer. Secondly, a corrected bite improves function. Chewing becomes more efficient and comfortable, potentially aiding digestion. Speech impediments related to tooth position can also be resolved. Proper alignment reduces abnormal wear patterns on tooth enamel, preventing premature erosion and the need for restorative work down the line. Thirdly, orthodontia can alleviate undue stress on the jaw muscles and joints (TMJs), potentially reducing headaches, neck pain, or clicking/popping sounds associated with TMJ disorders. Fourthly, let’s not underestimate the profound psychological benefits. A smile you’re proud of can significantly boost self-esteem and confidence, impacting social interactions, professional opportunities, and overall quality of life. Finally, achieving proper alignment can provide long-term health benefits by creating a more stable oral environment less prone to future problems, potentially saving discomfort, time, and expense associated with extensive dental work later. These combined benefits – improved hygiene, better function, reduced pain, enhanced confidence, and long-term stability – underscore why orthodontia is considered a vital component of comprehensive oral healthcare, offering value that lasts a lifetime.

What Treatments Fall Under Orthodontia and What Qualifies?

So, we know what orthodontia is and why it’s important. Now, let’s look at the how. What specific treatments and procedures actually fall under the umbrella of orthodontia? It’s a common misconception that orthodontia equals traditional metal braces, end of story. While braces are certainly a cornerstone and highly effective tool, the field encompasses a much broader spectrum of diagnostic methods, appliances, and interventions aimed at achieving that ideal alignment and bite. Essentially, any procedure or device used by a dental professional (typically an orthodontist) with the specific goal of diagnosing, preventing, or correcting malpositioned teeth and jaws qualifies as orthodontia. This ranges from early interventions in young children designed to guide jaw growth and make space for permanent teeth, to comprehensive treatment for adolescents and adults using various types of braces or aligners, right through to the crucial retention phase that maintains the results. The scope includes not only the active movement of teeth but also the planning stages involving detailed analysis of facial structure, jaw relationships, and tooth positioning, as well as the follow-up care required for long-term stability. Understanding this broad scope helps clarify that orthodontia is a comprehensive process tailored to individual needs, utilizing a diverse toolkit to achieve the desired outcome, whether the issue is minor crowding or a complex skeletal discrepancy. It’s about the purpose – correcting alignment and bite – rather than being defined solely by a single type of appliance.

What is Generally Considered Orthodontia? Beyond Just Traditional Braces

When we talk about what’s “generally considered orthodontia,” we need to think expansively. Yes, traditional metal braces – those brackets and wires synonymous with teenage years for many – are a classic example. But the field is far more diverse. Orthodontia encompasses the entire process, starting with the initial consultation and detailed diagnostics. This includes taking X-rays (like cephalometric and panoramic views), creating plaster models or digital 3D scans of the teeth, and taking clinical photographs to fully assess the patient’s unique situation. Then comes the treatment planning, where the orthodontist maps out the strategy for correction. The active treatment phase involves various appliances. Beyond metal braces, there are ceramic (tooth-colored) braces, lingual braces (fitted to the back of the teeth, making them virtually invisible), and self-ligating braces (which use a sliding mechanism instead of elastic ties). Furthermore, clear aligner therapy, popularized by brands like Invisalign, is a major component of modern orthodontia, using a series of custom-made plastic trays to incrementally shift teeth. Orthodontia also includes appliances used for dentofacial orthopedics, such as palatal expanders to widen the upper jaw, headgear (less common now but still used), or functional appliances to influence jaw growth. Finally, the retention phase, involving retainers (both removable and fixed), is absolutely considered part of orthodontic treatment, as it’s essential for maintaining the corrected positions. Therefore, any intervention focused on diagnosing, preventing, guiding, or correcting tooth and jaw alignment falls squarely within the realm of orthodontia.

Do Retainers Count as an Orthodontic Treatment?

Absolutely, unequivocally, yes. Retainers are not merely an optional accessory after braces come off; they are a critical and indispensable phase of comprehensive orthodontic treatment. Think of active orthodontic treatment (like braces or aligners) as the phase where teeth are moved into their desired positions. However, the tissues surrounding the teeth – the bone, periodontal ligaments, and gums – need time to adapt and stabilize around these new positions. Teeth possess a natural tendency to “relapse,” or drift back towards their original spots, especially in the months immediately following appliance removal. This is where retainers come in. Their sole purpose is to retain the teeth in their corrected alignment, holding them steady while the supporting structures firm up. Without consistent retainer wear as prescribed by the orthodontist, the results achieved through months or years of active treatment can be partially or even fully undone. There are several types of retainers: Hawley retainers (the traditional wire-and-acrylic type), Essix retainers (clear, vacuum-formed plastic trays similar to aligners), and fixed or bonded retainers (a thin wire permanently glued to the back of the front teeth). Each has its pros, cons, and specific use cases. The orthodontist determines the best type and wear schedule (e.g., full-time initially, then nights-only) for each patient. Because they are essential for the long-term success and stability of the outcome, retainers are fundamentally integrated into the overall orthodontic treatment plan, representing the crucial final stage of the process. Neglecting retainer wear is akin to investing heavily in building a house and then failing to maintain the foundation.

Is Invisalign Classified as Orthodontia?

Yes, Invisalign and similar clear aligner systems are definitively classified as orthodontia. They represent a specific method or appliance type used within the broader field of orthodontic treatment to achieve tooth movement and bite correction. Developed as an aesthetic alternative to traditional braces, Invisalign utilizes advanced 3D computer-imaging technology to create a series of custom-made, clear, removable plastic trays (aligners). Each aligner in the series is worn for about one to two weeks, applying gentle, controlled forces to specific teeth, gradually shifting them into position according to the orthodontist’s predetermined plan. Patients progress through the series of aligners until the final desired alignment is reached. While the mechanics differ from braces (which use brackets and wires), the fundamental principle and goal are the same: applying precise forces over time to move teeth through bone into a better position. Invisalign is capable of treating a wide range of orthodontic issues, from simple crowding and spacing to more complex bite problems, although very severe cases might still be better suited to traditional braces or require a combination approach. The treatment is planned, prescribed, and monitored by an orthodontist or a specially trained dentist. Therefore, despite its different appearance and mechanism, Invisalign therapy is squarely within the domain of orthodontia, offering patients a less conspicuous way to achieve the same health and aesthetic benefits associated with straighter teeth and a properly aligned bite. It’s simply another sophisticated tool in the modern orthodontist’s toolkit.

What Specific Dental Problems Can Orthodontia Correct?

Orthodontia is the go-to solution for a surprisingly wide array of dental and facial irregularities. Its reach extends far beyond simply straightening teeth that look a bit crooked. Orthodontists are trained to diagnose and treat the full spectrum of malocclusions and related issues. Common problems corrected include: Crowding, where there isn’t enough space in the jaw for teeth to align properly, leading to overlapping and rotated teeth. Spacing, the opposite of crowding, characterized by noticeable gaps between teeth, often due to missing teeth or a discrepancy between tooth size and jaw size. Overbite (or Deep Bite), where the upper front teeth excessively cover the lower front teeth. Underbite, where the lower front teeth protrude forward, sitting in front of the upper front teeth. Crossbite, occurring when upper teeth bite incorrectly inside the lower teeth, which can affect single teeth or groups of teeth in the front or back. Open Bite, where the upper and lower front teeth don’t overlap or meet when biting down, leaving a vertical gap. Misplaced Midline, when the center of the upper front teeth doesn’t align with the center of the lower front teeth. Beyond individual tooth positioning, orthodontia also addresses misaligned jaw growth and discrepancies between the upper and lower jaws (skeletal issues), often using dentofacial orthopedic techniques in growing patients. Furthermore, orthodontic treatment is frequently a crucial preparatory step for other dental procedures, such as creating adequate space for dental implants, bridges, or veneers, ensuring the success and longevity of subsequent restorative work.

How is Orthodontia Applied in Real-Life Situations for Better Smiles and Health?

The real-life applications of orthodontia are profoundly impactful, touching everyday aspects of health and well-being across all age groups. For children, interceptive orthodontics can make a huge difference. For instance, using a palatal expander can widen a narrow upper jaw, improving the bite, creating space for permanent teeth to erupt properly, and potentially even improving breathing by widening the nasal airway. Early intervention can simplify or even eliminate the need for more complex treatment later. For adolescents, comprehensive treatment (often with braces or aligners) during their growth spurt is common. Correcting an overbite, for example, not only improves the profile and smile but also protects the lower front teeth from excessive wear and potential trauma to the upper front teeth. Straightening crowded teeth makes it significantly easier for them to maintain good oral hygiene during a life stage where habits are still forming, reducing future cavities and gum issues. For adults, the applications are equally relevant. Many adults seek treatment they couldn’t have as children, often choosing discreet options like clear aligners. Correcting long-standing alignment issues can alleviate jaw pain (TMD), reduce headaches, improve chewing efficiency for better digestion, and prepare their mouths for necessary restorative work like implants. A common scenario involves aligning teeth that have shifted over time due to tooth loss or gum disease, restoring function and aesthetics. In essence, orthodontia translates into tangible daily improvements: eating favourite foods without discomfort, speaking more clearly, cleaning teeth effectively, avoiding future dental complications, and, undeniably, smiling with greater confidence in social and professional settings.

What Are the Different Categories or Types Within Orthodontics?

While the overarching goal of orthodontics – achieving proper tooth and jaw alignment – remains constant, the field isn’t monolithic. Practitioners often think about treatment in different categories or phases, largely based on the patient’s age, developmental stage, and the specific objectives of the intervention. Understanding these categories helps clarify when and why certain treatments are recommended. It’s not always about waiting until all permanent teeth are in; sometimes, intervening earlier provides significant advantages by working with the body’s natural growth processes. Similarly, the focus of treatment can sometimes lean more heavily towards aesthetic improvement, although functional correction is almost always an inherent component. These categorizations provide a framework for orthodontists to strategize the most effective approach for each unique patient situation, ensuring timely and appropriate care. Recognizing these distinctions allows patients and parents to better understand the rationale behind proposed treatment plans, whether it’s a simple space maintainer for a young child, comprehensive braces for a teenager, or aesthetically focused aligners for an adult. It highlights the tailored nature of orthodontic care, adapting its strategies to meet diverse needs and goals across different life stages and clinical presentations. Let’s delve into some common ways orthodontics is classified.

Can Orthodontics Be Broken Down into 3 Main Categories?

Yes, it’s quite common and useful to think of orthodontic treatment in terms of three broad categories, primarily based on timing and objectives: Preventive, Interceptive, and Comprehensive Orthodontics.

Preventive Orthodontics focuses on actions taken to prevent malocclusions from developing in the first place. This often involves early detection of potential problems and mitigating factors. Examples include placing space maintainers to hold space for unerupted permanent teeth when baby teeth are lost prematurely, discouraging harmful habits like prolonged thumb sucking or tongue thrusting that can affect dental development, and ensuring timely extraction of stubborn baby teeth that might impede the eruption path of permanent ones. The goal here is proactive avoidance of future issues.

Interceptive Orthodontics, also known as Phase I treatment, typically occurs when a child has a mix of baby and permanent teeth (mixed dentition, usually between ages 7 and 11). This phase aims to “intercept” a developing problem, guide jaw growth, and create a better environment for the incoming permanent teeth. Treatments might include palatal expanders to correct crossbites or create space, appliances to correct harmful bites or guide jaw growth (addressing significant overbites or underbites early), or partial braces to align front teeth. Interceptive treatment doesn’t always eliminate the need for later treatment, but it can often make subsequent phases simpler, shorter, and potentially less invasive.

Comprehensive Orthodontics, often referred to as Phase II treatment (or the sole phase if interceptive wasn’t needed), is what most people picture: full treatment, usually with braces or aligners, applied once most or all permanent teeth have erupted (typically during adolescence or adulthood). This aims to correct established malocclusions, align all the teeth perfectly, and establish an ideal, stable bite. Understanding these categories helps patients appreciate why an orthodontist might recommend treatment at different life stages, leveraging growth or addressing problems before they become more complex.

What is Cosmetic Orthodontia and How Does It Differ?

Cosmetic orthodontia isn’t strictly a separate category defined by professional organizations, but rather a term used to describe orthodontic treatment where the primary driving motivation for the patient is the improvement of the smile’s aesthetic appearance. While virtually all orthodontic treatment results in a more attractive smile, the emphasis in “cosmetic orthodontia” is squarely on enhancing the visual harmony and alignment of the teeth, particularly the front ones that are most visible. Patients seeking this type of treatment might be less concerned with minor functional bite issues (though these are often addressed concurrently) and more focused on achieving perfectly straight, evenly spaced teeth for a confidence boost. This focus often influences treatment choices. Patients prioritizing aesthetics might strongly prefer less visible appliances like clear aligners (Invisalign) or ceramic braces, even if traditional metal braces could potentially be slightly faster or more effective for certain complex movements. Treatment plans might sometimes be tailored to address primarily the “social six” – the upper front teeth most prominent when smiling. However, it’s crucial to understand that reputable orthodontists will never compromise functional health solely for aesthetics. Even when the patient’s main goal is cosmetic, the orthodontist ensures the treatment results in a stable, healthy bite that doesn’t create new problems. So, while the emphasis might differ, the underlying principles of sound orthodontic practice remain. Cosmetic orthodontia essentially highlights the patient’s primary goal, often leading to the selection of aesthetically pleasing appliance options to achieve functionally sound and visually appealing results. It acknowledges the powerful role a great smile plays in self-perception and confidence.

How Does Orthodontia Differ from General Dentistry and Other Specific Procedures?

Navigating the world of dental care can sometimes feel like alphabet soup, with various specialties and procedures. It’s essential to draw clear lines between orthodontia and other areas, particularly general dentistry and specific treatments like root canals, to understand where to turn for specific needs. While all dentists share a foundation in oral health, orthodontia occupies a distinct, specialized niche requiring significant additional training focused exclusively on diagnosing and correcting alignment issues. General dentists are the primary care providers for your overall oral health, managing a wide range of routine and restorative needs. Orthodontists, however, are the specialists you consult when the primary concern is the position of your teeth and the alignment of your jaws. Confusing these roles or mistaking one type of procedure for another (like thinking orthodontia involves treating nerve infections) can lead to misunderstandings about treatment options and expectations. Clarifying these distinctions empowers patients to seek the right expertise for their concerns, ensuring they receive appropriate and effective care. Understanding that orthodontia is a specific discipline focused on mechanics, growth, and alignment helps differentiate it from the broader maintenance and restorative work handled by general dentists, or the endodontic work involved in procedures like root canals. Let’s explicitly address some common points of confusion.

Is Orthodontia the Same as a Root Canal? Clarifying the Procedure Differences

No, absolutely not. Orthodontia and root canal therapy are entirely different dental procedures addressing completely unrelated problems. Confusing the two is like mistaking a structural engineer for an electrician – both work on buildings, but their focus is vastly different.

Orthodontia, as we’ve established, is the specialty focused on diagnosing, preventing, and correcting malpositioned teeth and jaws (bad bites). It uses appliances like braces or aligners to gradually move teeth into better alignment over weeks, months, or years. The goal is improved function, health, and aesthetics related to tooth position and jaw alignment.

Root canal therapy (RCT), on the other hand, is an endodontic procedure (endo = inside, odont = tooth) performed, usually by a general dentist or an endodontist (root canal specialist), to treat infection or inflammation inside a tooth’s pulp chamber and root canals. The pulp contains the tooth’s nerve and blood vessels. When it becomes infected (due to deep decay, cracks, or trauma), it can cause severe pain and lead to an abscess. RCT involves removing the infected pulp, cleaning and disinfecting the internal canals, and then filling and sealing the space. The purpose is to save a badly damaged or infected tooth from needing extraction.

So, orthodontia deals with the external position and alignment of teeth and jaws, while a root canal deals with the internal health of an individual tooth’s nerve tissue. There is zero overlap in the procedures themselves or the conditions they treat.

What is the Difference Between General Dental Care and Orthodontia?

The difference between general dental care and orthodontia lies primarily in scope and specialization.

A General Dentist is your primary oral healthcare provider, akin to a family doctor for your mouth. They offer a broad range of services focused on maintaining overall oral health. This includes routine check-ups, cleanings, fillings for cavities, crowns, bridges, dentures, basic gum disease treatment, teeth whitening, and often procedures like extractions or root canals. They are trained to diagnose and treat a wide spectrum of dental conditions and diseases. Think of them as the first line of defense for your oral health.

Orthodontia, conversely, is a specialty within dentistry. An Orthodontist is a general dentist who has completed an additional two to three years of full-time, intensive residency training focused exclusively on orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics. Their practice is limited only to diagnosing, preventing, and treating malocclusions – problems with tooth alignment and jaw relationships. They possess in-depth knowledge of facial growth, biomechanics (how teeth move), and the various appliances used to guide teeth and jaws into their correct positions. While a general dentist might identify that a patient could benefit from orthodontic treatment (e.g., noticing crowded teeth or a significant overbite during a check-up), they will typically refer the patient to an orthodontist for specialized assessment and treatment. General dentists manage overall oral health; orthodontists are the experts specifically dedicated to straightening teeth and aligning jaws.

Is There a Difference Between the Terms “Orthodontics” and “Orthodontia”?

As touched upon earlier, the distinction between “orthodontics” and “orthodontia” is subtle and, in everyday practical terms, largely insignificant for patients. Both terms refer to the same fundamental concept: the dental specialty concerned with correcting misaligned teeth and jaws. However, there is a slight nuance based on etymology and common usage.

Orthodontia, stemming from “orthos” (straight) and “odous” (tooth), might slightly emphasize the condition or the treatment process itself – the act of making teeth straight. You might see it used in older texts or more formal contexts.

Orthodontics, with the “-ics” suffix denoting a field of study or practice (like physics, mathematics), is the more contemporary and widely accepted term for the dental specialty as a whole. It refers to the science, the techniques, the professional discipline practiced by orthodontists. Professional organizations (like the American Association of Orthodontists), dental schools, and most modern practitioners consistently use “orthodontics” when referring to their field.

So, technically, orthodontics is the name of the specialty, and orthodontia could be seen as the practice or result of that specialty. But for anyone outside the nitty-gritty of dental terminology – patients, the general public – the terms are effectively interchangeable. Using either term will successfully convey the idea of treatment involving braces, aligners, retainers, and the goal of achieving a straight, healthy bite. Don’t get hung up on the difference; both roads lead to understanding the same essential service.

What Are Some Related Concepts and Where Does Orthodontia Originate From?

To fully grasp the landscape of orthodontia, it’s helpful to understand its neighbours – related concepts within dentistry – and to take a quick glance back at its historical roots. Orthodontia doesn’t exist in a vacuum; it interacts closely with other dental disciplines and concepts, particularly concerning facial growth and development. Understanding these connections provides a richer context for why and how orthodontic treatment works, especially in growing patients. Furthermore, knowing a bit about its origins helps appreciate how far the field has come. The desire for straight teeth isn’t a modern invention; rudimentary attempts at correcting alignment date back centuries. Tracing this evolution highlights the ingenuity and scientific advancements that have transformed orthodontia from crude appliances to the sophisticated, comfortable, and highly effective treatments available today. Exploring related fields like dentofacial orthopedics clarifies the orthodontist’s role in managing not just tooth position but also the development of the facial skeleton. This broader perspective underscores the comprehensive nature of the specialty and its deep integration within the overall framework of oral and facial health, illuminating its journey from ancient aspirations to a precise modern science.

How is Dentofacial Orthopedics Defined in Relation to Orthodontia?

Dentofacial orthopedics is a term that often appears alongside orthodontics, and for good reason – they are intimately related, and typically practiced by the same specialist. While “orthodontics” primarily involves managing tooth movement, “dentofacial orthopedics” specifically focuses on guiding the growth and development of the facial bones, mainly the jaws (maxilla and mandible), usually during childhood and adolescence while growth is still occurring. “Dento” refers to teeth, “facial” refers to the face, and “orthopedics” comes from Greek words meaning “straight” or “correct” (“orthos”) and “child” (“paideia”), historically referring to correcting skeletal deformities. So, dentofacial orthopedics is essentially about modifying facial growth to correct imbalances between the upper and lower jaws and ensure they relate properly to each other and the rest of the face. This is often achieved using specialized appliances that apply forces to influence bone growth – examples include headgear (to restrain upper jaw growth), functional appliances (like Herbst or Twin Block appliances, designed to encourage lower jaw growth in cases of significant overbite), and palatal expanders (to widen a narrow upper jaw). Orthodontists receive training in both orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics during their residency. Treatment often involves phases: perhaps an orthopedic phase first to address jaw discrepancies while the patient is growing, followed by an orthodontic phase (braces or aligners) to fine-tune tooth alignment once jaw growth is more stable. Think of it as orthodontics handling the teeth, while dentofacial orthopedics handles the foundational bone structure supporting them, working together for optimal results.

Where Does the Field of Orthodontia Come From? A Brief History

The quest for a perfect smile is ancient. Archaeological evidence reveals crude attempts by Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans to straighten teeth using metal bands and wires – rudimentary orthodontia, indeed! However, orthodontics as a distinct dental science began to truly take shape much later. The 18th century saw figures like Pierre Fauchard, often called the “father of modern dentistry,” describe appliances for tooth alignment in his influential book “The Surgeon Dentist.” Progress accelerated in the 19th century. Norman W. Kingsley wrote the first comprehensive text on oral deformities in 1880, and J. N. Farrar pioneered the concept of using mild, intermittent forces to move teeth over time. But the pivotal figure is widely considered to be Edward H. Angle (1855-1930), hailed as the “father of modern orthodontics.” Around the turn of the 20th century, Angle was instrumental in establishing orthodontics as dentistry’s first specialty. He developed the first simple classification system for malocclusions (Angle’s classifications – Class I, II, III – still used today), invented numerous appliances (like the edgewise bracket, a precursor to modern braces), and founded the first school dedicated solely to orthodontic training in 1900. The 20th century saw continuous refinement: stainless steel replaced gold and silver, bonding techniques allowed direct attachment of brackets to teeth (eliminating the need for full bands on every tooth), and new appliance designs emerged. The late 20th and early 21st centuries brought digital technology (3D imaging, CAD/CAM aligners like Invisalign), improved materials, and a deeper understanding of biomechanics, making treatment more efficient, comfortable, and aesthetic than ever before. Orthodontia has evolved dramatically from ancient curiosities into a sophisticated, science-driven specialty.

Are There Any Disadvantages to Undergoing Orthodontic Treatment?

While the benefits of orthodontic treatment are substantial and often life-changing, it’s important to approach it with realistic expectations. Like any medical or dental intervention, orthodontia isn’t without potential downsides or challenges. Presenting a balanced view helps prospective patients make informed decisions and prepare for the commitment involved. These disadvantages aren’t typically severe health risks but rather factors related to comfort, aesthetics, hygiene demands, time, and cost that warrant consideration. Acknowledging these potential drawbacks doesn’t diminish the value of orthodontics, but rather highlights the importance of patient compliance and understanding throughout the process. From the initial soreness after adjustments to the diligence required for cleaning around appliances and the necessity of long-term retainer wear, the journey requires active participation. Furthermore, the financial investment and time commitment (often spanning one to three years) are significant factors for many individuals and families. Being aware of these aspects allows patients to weigh the pros and cons relative to their specific situation and goals, ensuring they embark on treatment fully prepared for the responsibilities and potential inconveniences alongside the anticipated positive outcomes. Open communication with the orthodontist about these concerns is key to navigating the treatment process smoothly and successfully.

- Discomfort and Soreness: Teeth need to be gently pushed and pulled to move, and this can cause soreness or discomfort, particularly for a few days after braces are initially placed or adjusted, or when switching to a new aligner tray. The gums and cheeks can also become irritated by brackets and wires initially, though dental wax can help manage this. Over-the-counter pain relievers are usually sufficient to manage soreness.

- Aesthetic Concerns: While options like ceramic braces and clear aligners are less conspicuous, traditional metal braces are quite visible. Some patients, particularly adults, may feel self-conscious about the appearance of braces during treatment. Even aligners, while clear, require attachments (small bumps of composite resin) on some teeth, which can be noticeable.

- Oral Hygiene Challenges: Cleaning teeth effectively becomes more difficult and time-consuming with braces. Food particles easily get trapped around brackets and wires, increasing the risk of plaque buildup, cavities (especially decalcification, or white spots), and gum inflammation (gingivitis) if meticulous hygiene isn’t maintained. Special brushes, floss threaders, or water flossers are often recommended. Aligners must be removed for eating and drinking anything other than water, and teeth must be brushed before reinserting them, requiring diligence throughout the day.

- Dietary Restrictions: Patients with fixed braces typically need to avoid hard, sticky, chewy, or crunchy foods (like hard candies, nuts, popcorn, chewing gum) that could damage the brackets or wires, potentially leading to emergency appointments and extending treatment time.

- Time Commitment: Orthodontic treatment requires regular appointments, typically every 4-8 weeks, for adjustments, monitoring progress, or receiving new aligners. The overall treatment duration can range from several months to a few years, depending on the complexity of the case. This requires a consistent time commitment from the patient.

- Financial Investment: Orthodontic treatment represents a significant financial cost. While payment plans are often available and some insurance policies offer partial coverage, it remains a considerable expense that needs careful budgeting.

- Potential for Relapse: As mentioned earlier, teeth have a tendency to shift back after treatment. Lifelong retainer wear (often nightly after an initial full-time period) is usually necessary to maintain the results permanently. Non-compliance with retainer use is the most common reason for relapse.

- Root Resorption (Rare): In some rare cases, the roots of teeth can shorten slightly during orthodontic movement. This is usually minor and clinically insignificant, but orthodontists monitor for it.

Understanding these potential disadvantages allows patients to enter treatment fully informed and committed to the necessary care and compliance for a successful outcome.

Frequently Asked Questions About ‘what is a orthodontia’

Navigating the specifics of dental terminology can often lead to recurring questions. When it comes to understanding “orthodontia,” several key inquiries frequently pop up as people try to grasp the core concepts, differentiate it from related terms, and understand its scope. Addressing these common questions directly can help solidify understanding and clear up any lingering confusion. These FAQs often revolve around the basic definition, its relationship to the more common term “orthodontics,” what types of treatments are included, and the range of problems it solves. Providing concise, clear answers to these specific points serves as a valuable quick-reference summary, reinforcing the essential information covered throughout this guide. Think of this section as a rapid recap, hitting the highlights and directly tackling those nuances that might still be swirling in a reader’s mind. By revisiting these fundamental questions, we ensure the core message about what orthodontia entails is crystal clear, empowering readers with the confidence that they truly understand this vital dental specialty and its place within overall oral healthcare. Let’s quickly address some of the most frequently encountered questions surrounding the term and concept of orthodontia.

What Does the Term “Orthodontia” Specifically Mean?

The term “orthodontia” literally translates from its Greek roots: “orthos” meaning “straight” or “correct,” and “odous” meaning “tooth.” So, at its most basic level, orthodontia means “straight tooth.” However, its practical meaning extends beyond just individual teeth to encompass the broader goal of correcting irregularities in the alignment of teeth and the relationship between the jaws (the bite or occlusion). It refers to the branch of dentistry specifically focused on diagnosing, preventing, and treating these alignment issues, often through the use of appliances like braces or aligners. While the term “orthodontics” is more commonly used today to refer to the specialty itself, “orthodontia” remains a valid term, often seen in more formal contexts or older literature, fundamentally pointing to the process and outcome of achieving correctly positioned teeth and jaws. It underscores the primary objective: creating a functionally sound and aesthetically pleasing arrangement within the mouth. Think of it as the practice aimed at achieving that “straight tooth” ideal, encompassing all the necessary steps from diagnosis to treatment completion and retention for long-term stability and oral health benefits. It’s the foundational concept for correcting bites and aligning smiles.

And What About “Orthodontics”? Understanding its Meaning

“Orthodontics” is the more contemporary and widely accepted name for the dental specialty itself. That “-ics” suffix generally denotes a field of study or practice, similar to “physics” or “genetics.” Therefore, orthodontics refers to the entire science, art, and practice dedicated to the diagnosis, prevention, interception, and treatment of malocclusions (improper bites) and other dental and facial irregularities related to alignment. It encompasses the body of knowledge, the diagnostic procedures, treatment planning philosophies, the various types of appliances used (braces, aligners, retainers, orthopedic devices), and the ongoing research within this specialized field. While “orthodontia” might subtly emphasize the treatment or the condition being treated, “orthodontics” clearly defines the professional discipline that requires additional years of specialized post-doctoral training after dental school. It’s the term you’ll find designating the specialty board, academic departments, and professional associations (like the American Association of Orthodontists). In essence, an orthodontist is a specialist who practices orthodontics to provide orthodontia (the treatment). Functionally, for patients seeking care, the terms are often used interchangeably, both leading to the understanding of straightening teeth and correcting bite issues for improved health and appearance. Recognizing “orthodontics” as the name of the specialty underscores the advanced level of expertise involved.

What is Generally Considered Orthodontia? Beyond Just Traditional Braces

Orthodontia encompasses a far wider range of activities and appliances than just the traditional metal braces many people envision. Generally, any procedure, diagnosis, or appliance used with the specific intent of correcting tooth misalignment or improper jaw relationships falls under the umbrella of orthodontia. This begins with the comprehensive diagnostic phase, including detailed clinical exams, X-rays (cephalometric, panoramic), study models (plaster or digital 3D scans), and photographs. The treatment planning stage, where the strategy is mapped out, is integral. Then comes the active treatment phase, which can involve a variety of appliances: traditional metal braces, aesthetic ceramic braces, invisible lingual braces (behind the teeth), self-ligating braces, and, significantly, clear aligner therapy (like Invisalign). Furthermore, dentofacial orthopedic appliances used to guide jaw growth in younger patients – such as palatal expanders, headgear, or functional appliances (e.g., Herbst, Twin Block) – are a key part of orthodontia. Early interventions like space maintainers to hold room for permanent teeth are also included. Critically, the retention phase following active tooth movement, which involves wearing retainers (removable like Hawley or Essix, or fixed/bonded wires), is absolutely considered a vital part of the overall orthodontic treatment process, essential for maintaining the achieved results. Therefore, orthodontia is a comprehensive field utilizing diverse tools and strategies tailored to achieve optimal alignment and bite function.

Is There a Difference Between the Terms “Orthodontics” and “Orthodontia”?

While technically nuanced, for most practical purposes, especially from a patient’s perspective, there isn’t a significant functional difference between the terms “orthodontics” and “orthodontia.” Both refer to the same area of dental specialization focused on straightening teeth and correcting bite problems. The subtle distinction lies in common usage and etymology: “Orthodontia” (from Greek “straight tooth”) perhaps leans towards describing the actual treatment process or the condition being addressed. It feels slightly more rooted in the outcome. “Orthodontics” (with the “-ics” suffix denoting a field of study) is the more formal and widely used term for the dental specialty itself – the science, the practice, the discipline. It’s the term used by professional bodies and educational institutions. Think of it like this: a patient receives orthodontia (treatment) from a specialist practicing orthodontics (the field). However, in everyday conversation, insurance forms, or general articles, the terms are often used interchangeably without causing confusion. If someone talks about needing orthodontia or seeking orthodontic treatment, everyone understands they mean services related to braces, aligners, retainers, and achieving a properly aligned smile and bite. Focusing too much on the difference is unnecessary; both point towards the expert care provided by an orthodontist to improve dental alignment and function.

What Specific Dental Problems Can Orthodontia Correct?

Orthodontia is equipped to address a broad spectrum of dental alignment and bite issues, going far beyond simply making front teeth look straighter. The specific problems orthodontists routinely diagnose and correct include: Crowding: Insufficient space in the jaw causes teeth to overlap, twist, or become impacted. Spacing: Excessive gaps exist between teeth, often due to small teeth, large jaws, or missing teeth. Overbite (Deep Bite): Upper front teeth excessively overlap the lower front teeth vertically. Overjet: Upper front teeth protrude horizontally (“stick out”) significantly beyond the lower front teeth. Underbite: Lower front teeth protrude forward, sitting in front of the upper front teeth when biting. Crossbite: Upper teeth bite down inside the lower teeth; this can occur in the front (anterior crossbite) or back (posterior crossbite). Open Bite: A vertical gap exists between the upper and lower teeth when biting down, meaning they don’t meet or overlap. Misplaced Midline: The center line between the upper two front teeth doesn’t align with the center line between the lower two front teeth. Impacted Teeth: Teeth (often canines or wisdom teeth) that fail to erupt properly into the dental arch. Beyond tooth positions, orthodontia, often incorporating dentofacial orthopedics, addresses skeletal discrepancies involving misaligned jaw growth or size differences between the upper and lower jaws. It’s also crucial for pre-prosthetic alignment, creating ideal spacing and positioning before placement of implants, bridges, or veneers.