Table of Contents

ToggleKey Takeaways

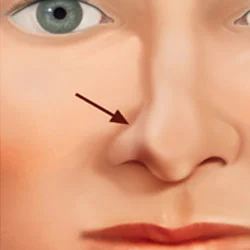

- Nostril collapse, or nasal valve collapse, occurs when nostril sidewalls weaken and are drawn inward during inhalation, obstructing airflow.

- Common symptoms include difficulty breathing through the nose (especially with exertion), chronic nasal congestion, visible nostril caving, mouth breathing, snoring, and disrupted sleep.

- Causes range from trauma or injury to the nose, previous nasal surgery (like rhinoplasty), the natural aging process, to congenital weaknesses in nasal structure.

- Diagnosis involves a doctor’s evaluation including patient history, visual inspection, the Cottle maneuver, and often nasal endoscopy.

- Non-surgical options like nasal dilator strips or internal nasal stents offer temporary relief.

- Surgical fixes include cartilage grafts, specialized suturing techniques, the LATERA® absorbable nasal implant, and functional rhinoplasty to reinforce nasal structures.

- Leaving nostril collapse untreated can lead to worsening breathing issues, poor sleep quality, contribute to obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and diminish overall quality of life.

What Exactly Is Nostril Collapse, and How Can It Affect Your Breathing and Sleep?

At its core, nostril collapse describes a situation where the nostril, or more accurately, the sidewall of the nostril (the ala), weakens and is drawn inward during inhalation. Instead of maintaining its open, supportive structure to allow air to flow freely, it narrows or even completely obstructs the passage. Imagine trying to suck a thick milkshake through a flimsy paper straw – as you inhale, the straw collapses. A similar principle applies here. This phenomenon is often, and more precisely, referred to as nasal valve collapse. The nasal valve is the narrowest part of the entire nasal airway, acting as a crucial gateway for air. It has two main components: the internal nasal valve, located further inside where the upper lateral cartilage meets the septum (the wall dividing your nostrils), and the external nasal valve, which is essentially the nostril opening itself, supported by the lower alar cartilages. When either of these areas lacks sufficient structural integrity, the negative pressure created during inspiration can overcome the cartilage’s ability to stay rigid, leading to that characteristic inward caving. The impact on breathing can range from a subtle annoyance to a significant impediment. You might find yourself exerting more effort just to draw air in through your nose, a sensation that can be particularly pronounced during physical activity when your body demands more oxygen. This increased nasal resistance forces many to become chronic mouth breathers, which brings its own set of problems like dry mouth and an increased risk of throat infections. When night falls, the consequences can be even more disruptive. The struggle for air can manifest as loud snoring, frequent awakenings, and generally poor, unrefreshing sleep. In more severe cases, nostril collapse can contribute to, or exacerbate, conditions like obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), where breathing repeatedly stops and starts throughout the night. Understanding these nasal valve issues is the first critical step towards addressing the frustrating cycle of difficult breathing and disturbed sleep, allowing individuals to seek appropriate solutions for a problem that deeply affects daily life and overall health. The seemingly simple act of breathing is, in fact, a complex mechanical process, and when the nostril structure is compromised, the ripple effects are felt far and wide.

What Are the Different Types of Nasal Valve Collapse to Be Aware Of?

Understanding the nuances of nasal valve collapse requires distinguishing between its primary types, as the location and specific structures involved dictate the symptoms and often, the most effective treatment approaches. The two principal categories are internal nasal valve collapse and external nasal valve collapse. Think of the internal valve as the inner gatekeeper and the external valve as the outermost entry point.

Internal nasal valve collapse occurs deeper within the nasal passage, at a critical junction formed by the septum (the central wall dividing the nostrils), the lower edge of the upper lateral cartilages (the paired cartilages forming the middle third of the nasal bridge), the head of the inferior turbinate (a structure within the nasal passage that humidifies air), and the nasal floor. This area is naturally the narrowest segment of the nasal airway, forming an angle of about 10-15 degrees in a typical Caucasian nose. When the upper lateral cartilages are weak, too medially positioned, or lack adequate support from the septum, they can be sucked inward towards the septum during inspiration, significantly narrowing or closing off this vital airflow channel. Symptoms often include a feeling of blockage higher up in the nose, and patients may instinctively pull their cheek outwards (the Cottle maneuver) to temporarily open this area and improve breathing.

External nasal valve collapse, on the other hand, involves the nostril opening itself – the alar rim, the columella (the fleshy strut between the nostrils), and the nasal tip structures, primarily supported by the lower lateral (alar) cartilages. If these cartilages are inherently weak, malformed, damaged, or have been over-resected during a previous surgery, the nostril sidewall can visibly cave inward during inhalation. This is often more apparent externally; you might actually see the nostril slit becoming narrower as you breathe in. This type of collapse can also be influenced by the position and strength of the fibrofatty tissue that makes up the nostril wing.

Beyond these primary anatomical distinctions, collapse can also be classified by its behavior. Dynamic collapse is the most common, occurring specifically during inspiration due to negative pressure. Static collapse or stenosis implies a fixed narrowing that is present even at rest, without active inhalation, often due to scarring or severe structural deformity. Contributing factors can further refine these “types.” For instance, collapse secondary to previous rhinoplasty (iatrogenic collapse) has specific considerations, as does collapse resulting from trauma or congenital weakness. Identifying the precise location and nature of the collapse is paramount for a surgeon to tailor an effective repair strategy, as treatments for internal valve issues can differ significantly from those targeting the external valve.

What Are the Common Signs and Symptoms Indicating You Might Have a Collapsed Nostril or Nasal Valve?

Recognizing the chorus of complaints that often signal a collapsed nostril or nasal valve is the first step towards finding relief. These symptoms can range from mildly irksome to profoundly disruptive, painting a picture of compromised nasal airflow. One of the most prominent indicators is difficulty breathing through the nose, which might be persistent or more noticeable during physical exertion when your body’s demand for oxygen surges. This isn’t just a fleeting stuffiness; it’s a chronic sensation of obstruction, often described as feeling like you’re constantly trying to breathe through a narrow straw, and it can affect one or both sides of your nose. Accompanying this is often a nasal congestion or blockage that stubbornly refuses to yield to typical remedies for colds or allergies. While antihistamines or decongestants might offer fleeting relief if there’s an allergic component, the underlying structural issue remains, leading to a frustrating cycle of temporary fixes. Perhaps the most visually indicative sign is the visible caving in of the nostril sidewall upon inhalation. If you look in a mirror while taking a deep breath in through your nose, you might actually see the nostril (external collapse) or the area just above it (suggestive of internal collapse) narrowing or pinching shut. This visual cue is a strong pointer towards structural weakness. As a consequence of impaired nasal breathing, many individuals develop chronic mouth breathing. While it seems like a simple adaptation, mouth breathing bypasses the nose’s natural air filtration and humidification system, leading to a dry mouth, chapped lips, an increased susceptibility to sore throats and dental problems. The nighttime often amplifies these issues. Snoring or disrupted sleep is exceedingly common, as the narrowed airway vibrates or leads to increased effort in breathing, fragmenting sleep and leaving you feeling unrefreshed in the morning. This can escalate to symptoms consistent with obstructive sleep apnea. Finally, a persistent nasal stuffiness, especially during exertion, is another tell-tale sign. When you exercise, your body needs more air, and if the nasal valve can’t handle this increased demand due to weakness, the sensation of blockage becomes much more acute. Addressing the question, “Do You Have Nasal Airway Obstruction?” becomes critical here, as these symptoms collectively point towards a significant obstruction, with nostril or nasal valve collapse being a very likely culprit that warrants professional investigation to distinguish it from other causes of nasal blockage.

What Are the Primary Reasons and Underlying Factors That Cause a Nostril or Nasal Cartilage to Collapse?

The structural integrity of our nostrils and the all-important nasal valve can be compromised by a variety of factors, each contributing to the frustrating scenario of nostril collapse. Understanding these root causes is crucial for both prevention, where possible, and effective treatment. One of the most direct culprits is trauma or injury to the nose. A significant blow, whether from a sports accident, a fall, or an altercation, can fracture or dislocate the delicate cartilages that provide nasal support. Even if the nose doesn’t appear overtly crooked externally, the internal architecture can be disrupted, leading to weakened areas prone to collapse during inhalation. Another major contributor, and one that often brings patients to seek revision surgery, is previous nasal surgery, particularly rhinoplasty. While the goal of rhinoplasty is often to refine aesthetics or improve function, if too much cartilage is removed (over-resection), or if the existing cartilages are destabilized without adequate reconstruction and support, the nasal structures can weaken over time. This is often termed “iatrogenic collapse” (caused by medical intervention) and can lead to the question, “What causes a nose job to collapse?” The answer lies in the delicate balance between achieving the desired shape and preserving structural support – a balance that requires immense skill and foresight from the surgeon. The natural process of aging also plays a significant role. As we age, our bodily tissues, including cartilage, tend to lose some of their inherent strength, elasticity, and resilience. The supporting soft tissues and ligaments in the nose can also weaken, leading to a gradual drooping or loss of support for the nasal tip and sidewalls, making them more susceptible to collapse. Some individuals are born with congenital weaknesses or anatomical predispositions. This might mean they naturally have very narrow nasal passages, inherently thin or floppy alar (nostril) cartilages, or a particular nasal shape that makes the valve area more vulnerable to dynamic collapse even without any specific injury or surgery. Finally, though less common, certain medical conditions or diseases that affect cartilage integrity systemically can lead to nasal cartilage collapse. Conditions like relapsing polychondritis (an autoimmune disorder causing inflammation of cartilage throughout the body) or granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s) can weaken nasal structures. Addressing “How does nasal valve collapse occur?” mechanistically, it’s often a result of Bernoulli’s principle in action: as air is inspired, it speeds up through the narrow nasal valve, creating negative pressure. If the cartilaginous framework is weak, this negative pressure can suck the sidewalls inward, obstructing airflow.

Why Might One Nostril Seem to Close Up or One Side of the Nose Appear to Be Collapsing?

It’s a common and often perplexing experience: you feel like you can breathe relatively well through one nostril, while the other feels perpetually blocked or seems to visibly suck inwards when you inhale. This unilateral, or one-sided, nostril collapse isn’t arbitrary; it’s usually rooted in specific anatomical or historical factors affecting one side of your nasal structure more than the other. One primary reason for such asymmetry is localized trauma. If you’ve sustained an injury predominantly to one side of your nose, the cartilage and supporting structures on that side might be weakened, fractured, or displaced, while the other side remains relatively intact. This can create a scenario where only the damaged nostril succumbs to the negative pressure of inhalation. Similarly, previous nasal surgery that disproportionately affected one side can be a culprit. For instance, if a septoplasty (surgery to correct a deviated septum) involved more aggressive cartilage removal or alteration near one nasal valve area, or if a rhinoplasty focused on refining one nostril more than the other, this could lead to unilateral weakness and subsequent collapse. The inherent asymmetrical anatomical features of an individual’s nose can also predispose one side to collapse. Few faces are perfectly symmetrical, and this extends to the internal nasal structures. One upper lateral cartilage might be naturally weaker or positioned differently than its counterpart, or one alar cartilage might be less robust. Furthermore, the presence of a deviated septum can significantly contribute to unilateral collapse. If the septum deviates sharply towards one side, it can narrow the internal nasal valve angle on that side, making it more prone to collapse. Additionally, the deviation itself might impinge upon or destabilize the lateral cartilaginous structures on that side, reducing their ability to resist inspiratory forces. Sometimes, scar tissue formation following an injury or surgery can be more pronounced on one side, leading to contraction and distortion that compromises the nostril’s integrity. Understanding these potential causes of one-sided nostril collapse is crucial, as targeted treatment will often need to address the specific asymmetry to restore balanced nasal breathing. It’s rarely a random occurrence but rather a direct consequence of specific, often identifiable, structural imbalances.

If Previous Surgery Is a Cause, How Long After Rhinoplasty Can Your Nose Potentially Collapse?

The timeline for potential nostril collapse following a rhinoplasty (commonly known as a “nose job”) isn’t fixed; it can vary quite dramatically, manifesting either relatively soon after the procedure or, disconcertingly, emerging months or even years down the line. Understanding these different timeframes helps patients and surgeons anticipate and manage this unwanted complication. Early collapse, occurring within days to weeks post-surgery, is often due to more immediate structural instability. This could arise if the surgical plan didn’t incorporate sufficient supportive measures, especially if significant cartilage was removed or reshaped. Hematoma (a collection of blood) or infection, though relatively uncommon, can also compromise the healing of grafts or the integrity of the remaining structures in the early postoperative period, leading to a weakening and subsequent collapse. Inadequate splinting or premature trauma to the healing nose can also contribute to early deformities. More insidiously, later collapse can develop over a period of months to years. This delayed onset is often the result of several interconnected factors. As the initial post-surgical swelling gradually subsides over many months (it can take a year or even longer for all subtle swelling to resolve), underlying weaknesses that were previously masked can become apparent. The long-term forces of scar contracture also play a significant role; as scar tissue matures and tightens, it can pull on and distort the meticulously repositioned or grafted cartilages, leading to a gradual narrowing or collapse of the nasal valve or nostril sidewall. Furthermore, if cartilage grafts used for support were not adequately secured, or if they were too thin or underwent partial resorption (being broken down by the body) over time, their supportive function can diminish, allowing collapse to occur. This is particularly true if the surgeon was overly aggressive in removing cartilage, leaving behind a framework that is simply not robust enough to withstand the long-term stresses of breathing and tissue healing. The emphasis on surgeon experience is paramount here because a skilled surgeon anticipates these long-term forces, prioritizes structural support alongside aesthetic goals, and employs techniques designed to ensure lasting stability, thereby minimizing the risk of both early and late-onset collapse. It’s a stark reminder that rhinoplasty is a complex interplay of art and science, where preserving function is just as critical as achieving the desired form.

How Can You Determine if Your Nostril Is Collapsing, and How Is Nasal Valve Collapse Diagnosed by a Doctor?

Figuring out if your breathing difficulties stem from nostril or nasal valve collapse involves a combination of self-awareness and, crucially, a thorough professional evaluation. While you might pick up on some clues at home, a definitive diagnosis rests with a medical professional, typically an Ear, Nose, and Throat (ENT) specialist or a Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeon, who is well-versed in the intricacies of nasal anatomy and function. The diagnostic process usually begins with a detailed patient history. Your doctor will want to know about the nature of your symptoms: when did they start? Are they constant or intermittent? Do they worsen with exercise or in certain positions, like lying down? Have you had any previous nasal trauma or surgeries, especially rhinoplasty or septoplasty? This conversation provides essential context. Following this, a visual inspection of the nose, both externally and internally, is performed. The doctor will observe your nose at rest and then watch carefully as you breathe normally and then more deeply through your nose. They’re looking for that characteristic inward movement or collapse of the nostril sidewalls (alar collapse) or the area just above the nostrils (suggesting internal valve issues). A key diagnostic maneuver often employed is the Cottle maneuver. While the patient breathes quietly through their nose, the doctor will gently pull the cheek on one side away from the nose, laterally. This action manually splints open the internal and sometimes the external nasal valve. If this simple maneuver results in a significant subjective improvement in airflow on that side, it’s a strong indicator of nasal valve collapse. For a more detailed internal view, nasal endoscopy might be performed. This involves inserting a thin, flexible or rigid tube with a light and camera on the end (an endoscope) into the nasal passages. This allows the doctor to directly visualize the internal nasal valve area, assess the relationship between the septum and the upper lateral cartilages, look for scar tissue, and evaluate other structures like the turbinates that might be contributing to obstruction. It provides a magnified, illuminated view far beyond what can be seen with the naked eye alone. Sometimes, objective measurements like acoustic rhinometry or rhinomanometry may be used to quantify nasal airflow and resistance, though the clinical examination often provides the most practical diagnostic information for valve collapse.

Are There Ways to Tell at Home if You Might Have Nasal Valve Collapse?

While a definitive diagnosis of nasal valve collapse requires a professional medical assessment, there are indeed a couple of simple self-assessment techniques you can try at home that might offer valuable clues and suggest whether this issue could be contributing to your breathing difficulties. These methods essentially mimic parts of a clinical examination and can help you articulate your symptoms more clearly to a doctor. The most well-known of these is a version of the Cottle maneuver. To perform this yourself, stand in front of a mirror. First, breathe normally through your nose to get a baseline sense of your airflow. Then, place one or two fingertips on your cheek, just beside the nostril you want to test. Gently pull your cheek outward and slightly upward, away from the side of your nose. While holding your cheek in this position, take another breath in through your nose. If you notice a significant improvement in airflow on that side – if it suddenly feels much easier to breathe – this is a positive self-Cottle test and strongly suggests that weakness or narrowing in your nasal valve area (either internal or external) might be a factor in your nasal obstruction. Repeat this on the other side. Another straightforward observation involves simply watching your nostrils in a mirror as you inhale. Take a normal breath in through your nose, and then a deeper, more forceful one. Observe carefully: do the sides of your nostrils (the alae) visibly suck inward or narrow significantly? Does one or both seem to pinch shut or nearly so? This visible inward movement during inspiration is a direct sign of dynamic external nasal valve collapse, where the nostril cartilages lack the strength to resist the negative pressure of airflow. It’s important to approach these home tests with the right perspective. They are indicators, not definitive diagnoses. A positive finding warrants further investigation by an ENT specialist or a facial plastic surgeon. These professionals can perform a more comprehensive examination, differentiate nasal valve collapse from other potential causes of nasal obstruction (like a deviated septum, turbinate hypertrophy, or allergies), and discuss appropriate treatment options if a collapse is confirmed. These simple at-home maneuvers, however, can be an empowering first step in understanding your body and seeking the right help.

Can a Doctor Clearly See a Nasal Valve Collapse During an Examination?

Absolutely, a doctor experienced in nasal and sinus disorders can often clearly identify nasal valve collapse during a clinical examination, employing a combination of direct observation and specific diagnostic techniques. The visibility and method of detection can vary slightly depending on whether it’s an internal or external valve issue, but both are typically discernible to a trained eye. For external nasal valve collapse, which involves the nostril rim (alar cartilage) itself, the collapse can be quite obvious. The doctor will simply watch your nostrils as you breathe. During inspiration, particularly a slightly deeper or quicker breath, they will look for that tell-tale inward caving or “pinching” of the nostril sidewall. This is a direct visual confirmation of the alar cartilages being too weak or malpositioned to withstand the negative pressure of airflow. For internal nasal valve collapse, which occurs further inside the nose at the junction of the upper lateral cartilage and the septum, direct external visualization of the collapse itself might be more subtle to an untrained observer. However, the doctor will still observe the area just above the nostril for any signs of narrowing during inspiration. The key diagnostic tool here is the Cottle maneuver, performed by the physician. By gently retracting the cheek laterally, the doctor manually supports and opens the internal nasal valve area. A distinct subjective improvement in airflow reported by the patient (“Oh, I can breathe much better now!“) is a highly indicative sign of internal valve compromise. Furthermore, to get an even clearer picture of the internal nasal structures, particularly the internal nasal valve, the doctor will often perform nasal endoscopy. This procedure involves inserting a small, thin, lighted scope (either rigid or flexible) into the nasal passage. This provides a magnified, well-illuminated view of the internal nasal valve, allowing the doctor to directly assess the angle between the septum and the upper lateral cartilage, look for any scarring or narrowing, and observe how these structures behave during quiet and forced inspiration. They can see if the upper lateral cartilage is indeed collapsing medially towards the septum. Therefore, through a combination of careful observation of breathing patterns, strategic maneuvers like the Cottle test, and advanced visualization with endoscopy, a doctor can indeed clearly see the functional and anatomical evidence of nasal valve collapse, enabling an accurate diagnosis and the formulation of an appropriate treatment plan.

How Can a Collapsed Nostril or Nasal Valve Generally Be Fixed or Repaired?

When it comes to rectifying a collapsed nostril or nasal valve, the overarching treatment philosophy is elegantly straightforward: restore or enhance the structural support of the nasal sidewall to prevent its inward collapse during breathing, thereby widening the airway and improving airflow. Think of it like reinforcing a tent pole that’s too weak to hold up the canvas; the goal is to make the nasal passage resilient against the negative pressures of inhalation. The specific approach to achieving this can vary significantly, ranging from simple, non-invasive temporary aids to more definitive and complex surgical interventions. The choice of treatment isn’t one-size-fits-all; it’s a tailored decision based on a thorough evaluation of several factors. These include the severity of the collapse (is it a mild nuisance or a significant daily impediment?), the precise location and type of collapse (internal, external, or both?), the underlying cause (was it trauma, previous surgery, or congenital weakness?), the patient’s overall health and lifestyle, and, importantly, the patient’s preferences and goals. For individuals with mild symptoms or those seeking temporary relief, non-surgical options like external nasal dilator strips (which lift the skin over the nasal valve) or internal nasal dilators (small stents placed inside the nostrils) can provide immediate, albeit temporary, improvement, especially during sleep or exercise. However, for more significant or persistent collapse, these are often just stopgap measures. The more permanent solutions typically involve surgical repair. Surgical strategies, often falling under the umbrella of functional rhinoplasty or specific nasal valve repair procedures, aim to physically bolster the weakened areas. This might involve using cartilage grafts (harvested from the patient’s own septum, ear, or occasionally rib) to act as internal splints or spreaders, suturing techniques to reshape or suspend existing cartilages, or utilizing specialized implants designed to support the lateral nasal wall. General resources and concepts, such as those discussed by specialists like “Kaplan Sinus Relief,” often highlight these core strategies: identifying the weak point and strategically reinforcing it. Ultimately, the repair is about re-engineering the nasal airway for optimal, effortless function, allowing individuals to reclaim the simple, vital pleasure of easy breathing.

What Surgical Options Are Available to Treat Nasal Valve Collapse Effectively?

When non-surgical measures fall short or the nostril collapse is structurally significant, surgery often emerges as the most definitive and effective path to long-lasting relief. The fundamental goal of any surgical intervention for nasal valve collapse is to restore, reinforce, or reposition the cartilaginous and soft tissue framework of the nasal valve area, thereby preventing its inward collapse during inhalation and ensuring a more open, stable airway. Surgeons have a sophisticated toolkit of techniques, and the specific approach is meticulously tailored to the individual patient’s anatomy, the precise location (internal or external valve), and the severity of the collapse. One of the most common and highly effective strategies involves the use of cartilage grafts. These are small pieces of the patient’s own cartilage, typically harvested from the nasal septum (the wall between the nostrils), the ear (conchal cartilage), or, in more complex cases requiring substantial support, a rib (costal cartilage). These grafts are then carefully shaped and sutured into place to provide structural reinforcement where it’s needed most. Another cornerstone of surgical repair involves various suturing techniques. These can be used to reshape existing cartilages, suspend weakened tissues, or widen the angle of the nasal valve. For instance, “flaring sutures” can be used to pull the lower lateral cartilages outward, opening up the external nasal valve. More recently, innovative devices like the LATERA® absorbable nasal implant have offered a minimally invasive option for supporting the lateral nasal wall, particularly effective for certain types of lateral cartilage weakness contributing to nasal valve collapse. And for many, particularly if there are coexisting aesthetic concerns or other functional issues like a deviated septum, a functional rhinoplasty provides a comprehensive platform to address all these elements simultaneously. This isn’t just a “nose job” for looks; it’s a sophisticated reconstructive procedure focused on optimizing both form and, critically, function. The surgeon utilizes a combination of grafting, suturing, and cartilage reshaping techniques within the rhinoplasty framework to rebuild a strong, stable, and patent nasal airway. Each of these surgical avenues aims to transform a compromised nasal passage into a reliably open conduit for air, dramatically improving a patient’s ability to breathe freely and enhancing their overall quality of life.

How Can a Cartilage Graft Help in Repairing a Nasal Valve Collapse?

Cartilage grafts are the unsung heroes in the surgical repair of nasal valve collapse, acting as internal scaffolding to rebuild and reinforce the weakened structures of the nose. The principle is straightforward: if a part of the nasal framework is too weak or poorly positioned to resist the negative pressure of inhalation, introducing a carefully shaped piece of strong, supportive cartilage can restore its integrity. Surgeons typically harvest this cartilage from the patient’s own body to minimize risks of rejection or reaction. Common donor sites include the nasal septum (the wall dividing the nostrils, often accessible during the same surgery), the ear concha (the bowl-shaped part of the outer ear, providing naturally curved cartilage ideal for some nasal contours), or, for more extensive reconstruction, a small section of a rib (costal cartilage), which offers abundant and robust material.

Several types of cartilage grafts are specifically designed to address different aspects of nasal valve collapse:

- Spreader Grafts: These are perhaps the most well-known grafts for treating internal nasal valve collapse. They are small, rectangular struts of cartilage placed between the upper lateral cartilages and the dorsal septum (the bridge line of the septum). By “spreading” these structures apart, they effectively widen the internal nasal valve angle, opening up the airway at its narrowest point. This is akin to inserting a supportive beam to prevent a V-shaped roof from caving in.

- Alar Batten Grafts: These are specifically used to address external nasal valve collapse or weakness in the nostril sidewall (ala). These grafts, often curved and harvested from ear or rib cartilage, are placed in a pocket created within the nostril sidewall, spanning the area of maximal collapse. They act like a supportive rib or “batten” in a sail, providing rigidity to the alar rim and preventing it from caving inward during inspiration.

- Lateral Crural Strut Grafts: The lateral crura are the outer segments of the lower alar cartilages that form the nostril tip and rim. If these are weak, malpositioned, or buckled, lateral crural strut grafts – small reinforcing strips of cartilage – can be sutured alongside or beneath them to strengthen, straighten, or reposition them, thereby improving the support and contour of the external nasal valve.

- Alar Rim Grafts: These are very delicate grafts placed precisely along the edge of the nostril opening to provide support and prevent notching or collapse of the alar margin itself.

The beauty of using autologous (the patient’s own) cartilage is its biocompatibility and longevity. Once integrated, these grafts become a permanent part of the nasal structure, providing durable support and significantly improving airflow for individuals who have long struggled with the frustrating symptoms of nasal valve collapse. The surgeon’s skill lies in selecting the right type of graft, harvesting it appropriately, and meticulously shaping and securing it to achieve the optimal functional outcome.

How Can Suturing Techniques Be Used to Address Nasal Valve Collapse?

While cartilage grafts provide invaluable structural reinforcement, suturing techniques offer a versatile and often complementary approach to surgically correcting nasal valve collapse, allowing surgeons to reshape, reposition, and stabilize existing nasal cartilages without necessarily adding bulk. These meticulous stitching methods can be particularly effective for milder forms of collapse or when the primary issue is cartilage malposition rather than inherent weakness or deficiency. Think of it as a tailor expertly altering a garment to improve its fit and form, using stitches to create new contours and support.

Several specific suturing techniques are employed:

- Flaring Sutures (or Alar Flaring Sutures): These are designed to address external nasal valve collapse by widening the nostril aperture. The suture is strategically passed through the alar cartilages (lower lateral cartilages) and sometimes anchored to deeper, more stable structures like the pyriform aperture (the bony opening of the nose). When tightened, these sutures gently pull the alar cartilages outward, “flaring” the nostrils and preventing the sidewalls from collapsing inward during inspiration. This can be likened to opening a pair of curtains wider to let in more light.

- Suspension Sutures: These techniques aim to lift and support weakened cartilages, particularly the upper or lower lateral cartilages, by suspending them from more stable, superior structures like the nasal bones or remnants of the upper lateral cartilages. This can help to open the internal or external nasal valve by preventing downward or inward displacement of these crucial supportive elements.

- Lateral Crural Steal/Repositioning Sutures: These are used to alter the shape and position of the lateral crura (the outer segments of the nostril tip cartilages). By strategically placing sutures, a surgeon can effectively “steal” length from one part of the cartilage to reshape another or to rotate and stabilize the lateral crus, thereby improving its supportive capacity and preventing collapse of the external valve. This can convert a concave, weak lateral crus into a stronger, straighter, or even slightly convex supportive structure.

- Septal-Lateral Crural Sutures: These can be used to stabilize the relationship between the septum and the lateral cartilages, helping to maintain the patency of the internal nasal valve.

Suturing techniques are often used in conjunction with cartilage grafting, where grafts provide the primary support and sutures help to fine-tune the position and stability of the cartilages. In some cases, particularly if the cartilage quality is good but its position or shape is the main issue, sutures alone might be sufficient. The advantage of these techniques lies in their ability to utilize and optimize the patient’s existing tissues, potentially reducing the need for extensive grafting. A skilled surgeon will assess the specific anatomical deficits and choose the suturing methods that will best restore strength and openness to the nasal valve, ensuring a clear path for airflow.

What Is the LATERA® Nasal Implant, and How Long Does This Device Typically Last?

The LATERA® Absorbable Nasal Implant represents a significant innovation in the treatment of certain types of nasal valve collapse, particularly those caused by weakness or poor support of the lateral nasal wall (the side of the nose). It offers a minimally invasive approach to bolstering this area, thereby improving airflow. The LATERA implant is a small, rod-like device, typically made from a biocompatible and absorbable polymer called polylactic acid (PLLA), which has a long history of safe use in various medical applications, such as absorbable sutures. The implant is designed to be placed within the lateral nasal wall, parallel to the nasal bone and the lateral cartilage. The procedure for inserting LATERA is generally straightforward and can often be performed in an office setting under local anesthesia or as part of a more comprehensive nasal surgery in an operating room. Using a specialized delivery device, the surgeon creates a small pocket in the tissue of the lateral nasal wall and then deploys the implant into this pocket. Once in place, the LATERA implant provides immediate mechanical support to the underlying cartilage, effectively acting like an internal “tent pole” that props open the nasal passage and prevents the sidewall from collapsing inward during inhalation. This increased support helps to reduce nasal airway obstruction and improve breathing. A key feature of the LATERA implant is its absorbable nature. It is designed to gradually resorb and be replaced by the body’s own tissue over a period of approximately 18 months. However, the clinical benefit of the implant is intended to last much longer than the implant itself. As the PLLA material slowly dissolves, the body naturally forms a supportive fibrous capsule around the area where the implant was. This newly formed scar tissue continues to provide structural support to the lateral nasal wall, maintaining the improved airflow even after the implant material is fully gone. Clinical studies and patient reports have shown that the benefits of the LATERA implant, such as improved nasal breathing and reduced obstruction symptoms, can be sustained for several years post-implantation for many individuals. It’s an appealing option for patients with appropriate anatomy who are seeking a less invasive surgical solution for their nasal valve collapse, particularly when the issue is related to dynamic collapse of the upper or lower lateral cartilages.

What Are the Benefits of Rhinoplasty When Used for Addressing Nostril Collapse?

When nostril collapse or nasal valve dysfunction is the culprit behind breathing difficulties, a functional rhinoplasty emerges as a powerful and often definitive surgical solution, offering a constellation of benefits that extend beyond mere airflow improvement. Unlike purely cosmetic rhinoplasty, which focuses solely on altering the nose’s appearance, functional rhinoplasty prioritizes the restoration and enhancement of nasal breathing while also allowing for aesthetic refinements if desired. This comprehensive approach is one of its primary advantages. A key benefit is its ability to simultaneously address multiple structural issues within the nose that may be contributing to obstruction. During a functional rhinoplasty, the surgeon can not only repair the nasal valve collapse using techniques like spreader grafts, alar batten grafts, or supportive suturing, but also correct a deviated septum (septoplasty), reduce enlarged turbinates (turbinoplasty), and repair any damage from previous trauma or surgery, all in a single, integrated procedure. This holistic approach ensures that all potential sources of blockage are addressed, maximizing the chances of a successful functional outcome. Furthermore, functional rhinoplasty allows for the use of sophisticated grafting and suturing techniques that might be more challenging or less effective through more limited, endonasal (inside the nostril) approaches. The open rhinoplasty approach, for example, provides the surgeon with direct, unparalleled visualization of the entire nasal framework, allowing for precise placement of grafts and sutures to rebuild a strong, stable nasal valve and overall nasal structure. Another significant benefit is the potential for concomitant aesthetic improvement. Many patients with functional breathing problems due to structural issues like a collapsed or crooked nose also have cosmetic concerns. Functional rhinoplasty offers the unique opportunity to improve the nose’s appearance – perhaps refining the tip, straightening the bridge, or narrowing the nostrils – at the same time as the breathing pathways are being reconstructed. This dual benefit is highly appealing to many patients. Lastly, the results of a well-executed functional rhinoplasty, particularly in terms of structural support for the nasal valve, are generally long-lasting and durable. By rebuilding the nasal framework with the patient’s own cartilage, the surgeon aims to create a nose that not only looks good but, more importantly, functions optimally for years to come, significantly enhancing the patient’s quality of life by restoring the simple pleasure of effortless nasal breathing.

Can Nasal Valve Collapse Be Treated Effectively Without Resorting to Surgery?

While surgery often provides the most definitive and long-lasting solution for structural nasal valve collapse, there are indeed non-surgical options that can offer effective symptom management and relief for many individuals, particularly those with milder collapse, those who wish to avoid surgery, or those seeking temporary aid for specific situations like sleep or exercise. These conservative measures primarily work by mechanically stenting or supporting the nasal passages externally or internally, or by reducing mucosal factors that might exacerbate the sensation of collapse. One of the most common non-surgical treatments involves the use of nasal dilators. These come in two main forms:

- External nasal dilator strips (e.g., Breathe Right strips): These are adhesive strips applied across the bridge of the nose, over the area of the nasal valves. The spring-like bands embedded in the strip gently lift the skin and underlying soft tissues of the lateral nasal walls, pulling them outward. This action helps to open up the nasal valve area, reducing airflow resistance and making breathing easier. They are particularly popular for use during sleep to alleviate snoring and improve nasal airflow, or during exercise.

- Internal nasal dilators (or nasal stents): These are small, often soft, devices made of plastic or silicone that are inserted directly into the nostrils. They work by physically holding the nasal passages open from the inside, preventing the nostril sidewalls from collapsing inward during inhalation. Various designs are available, some reusable and some disposable.

The primary pros of nasal dilators are their immediate effect, non-invasiveness, and general ease of use. They can provide significant symptomatic relief for many. However, the main cons are that their effect is temporary (only while the device is in use), they don’t address the underlying structural problem, and some individuals may find them uncomfortable, cosmetically unappealing for daytime use, or experience skin irritation (with external strips) or mild discomfort inside the nose (with internal dilators).

Beyond dilators, certain lifestyle modifications can sometimes help. For instance, sleeping with the head of the bed elevated can reduce nasal congestion for some. For individuals whose nasal valve collapse symptoms are worsened by underlying conditions like allergic rhinitis or chronic sinusitis, treating these conditions effectively with medications (such as nasal corticosteroid sprays, antihistamines, or decongestants, under medical guidance) can reduce mucosal swelling. While this doesn’t fix the structural collapse itself, minimizing inflammation can lessen the overall sensation of blockage and make the collapse less symptomatic. It’s crucial to understand that these non-surgical options are primarily for managing symptoms rather than providing a permanent fix for an anatomical weakness. However, for many, they offer a valuable means of improving nasal breathing and quality of life without the need for surgical intervention, or can serve as a useful trial to confirm if improving valve patency indeed relieves their symptoms before committing to surgery.

What Happens if a Collapsed Nose or Nasal Valve Is Left Untreated Over Time?

Leaving a collapsed nose or nasal valve untreated might not seem like an urgent, life-threatening issue in the immediate sense, but over time, the cumulative effects of chronic nasal obstruction can lead to a cascade of undesirable consequences, significantly impacting one’s quality of life and potentially contributing to other health concerns. The most direct outcome is, naturally, the worsening or persistence of breathing difficulties. What might start as an occasional annoyance can evolve into a constant struggle for air through the nose, forcing an individual to rely heavily on mouth breathing. This chronic mouth breathing itself is problematic, leading to dry mouth, an increased risk of dental problems like cavities and gum disease, bad breath, and a greater susceptibility to throat and upper airway infections, as the nose’s natural air filtering and humidifying functions are bypassed. The impact on sleep quality is another major concern. Persistent nasal obstruction from untreated collapse frequently leads to loud snoring, fragmented sleep due to increased breathing effort, and frequent awakenings (even if not fully conscious). This can contribute to the development or exacerbation of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), a serious condition characterized by repeated pauses in breathing during sleep. Untreated OSA, in turn, is linked to an increased risk of hypertension, heart disease, stroke, and daytime cognitive impairment. Consequently, individuals with untreated nasal valve collapse often suffer from reduced quality of life. The constant sensation of nasal blockage, coupled with poor sleep, can lead to daytime fatigue, difficulty concentrating, reduced exercise tolerance, and an overall diminished sense of well-being. Activities that others take for granted, like enjoying the scent of food or exercising comfortably, can become challenging. There’s also a possibility, though not definitively established for all cases, that the chronic negative pressure exerted on already weakened nasal structures during inspiration could lead to further weakening or distortion of these structures over time, potentially making the collapse more pronounced or leading to secondary changes in nasal appearance. While people can, and often do, “live with” untreated nasal valve collapse by adapting their breathing patterns, the chronic strain and the array of associated symptoms mean that seeking treatment can unlock a significantly improved daily existence, restoring not just comfortable breathing but also better sleep, more energy, and an overall enhanced sense of health.

Does Nasal Valve Collapse Tend to Get Worse or More Severe Over Time?

The trajectory of nasal valve collapse over time isn’t uniform for everyone; for some, it might remain relatively stable, while for others, it can indeed progressively worsen. Several factors influence whether this condition is likely to become more severe. One significant contributor to potential worsening is the natural aging process. As we age, all bodily tissues, including the cartilages and soft tissues that support the nasal structure, gradually lose some of their elasticity, strength, and volume. This inherent weakening can cause an initially mild or moderate nasal valve collapse to become more pronounced as the supporting framework becomes less capable of resisting the negative pressures of inhalation. If the collapse is due to progressive underlying conditions, such as certain inflammatory disorders that affect cartilage (like relapsing polychondritis, though rare), then the severity of the collapse would naturally track the activity of the disease. In cases where the collapse is due to previous trauma or surgery that resulted in a marginally stable structure, the long-term forces of scar contracture and the constant stress of breathing can, over years, lead to further gradual distortion or weakening, making the collapse more symptomatic. Think of it like a compromised bridge that slowly sags further under continuous load. Furthermore, chronic inflammation within the nasal passages, perhaps from untreated allergies or chronic sinusitis, can cause persistent mucosal swelling. While this doesn’t worsen the structural collapse of the cartilage itself, it can reduce the already limited space within the nasal valve area, making the functional impact of the collapse feel much worse. The sensation of blockage can intensify even if the cartilaginous defect hasn’t changed. Conversely, a collapse that occurred due to a specific, one-time traumatic event, once the initial healing has occurred, might remain stable but chronically problematic if the structural damage wasn’t adequately repaired. In such instances, it might not get structurally “worse,” but the symptoms of obstruction will persist at a consistent level. The chronic negative inspiratory pressure itself, constantly tugging at weakened areas, is also theorized by some to potentially contribute to a slow, progressive worsening in susceptible individuals. Therefore, while not an absolute certainty for everyone, there’s a reasonable likelihood, particularly with age-related changes or inadequately supported structures, that nasal valve collapse can indeed become more severe or more symptomatic over time if left unaddressed.

How Serious Is a Nasal Valve Collapse, and Is It Possible to Live With the Condition?

The “seriousness” of a nasal valve collapse is best understood on a spectrum, heavily influenced by its severity and its impact on an individual’s daily life and overall health. In its mildest form, it might manifest as a minor annoyance – perhaps a slight stuffiness during vigorous exercise or when lying on one side. In such cases, individuals might adapt with minimal disruption to their lives. However, as the collapse becomes more pronounced, its seriousness escalates significantly. While nasal valve collapse is not typically considered a directly life-threatening condition in itself, its potential to severely impair quality of life is undeniable. The chronic struggle to breathe through the nose can lead to persistent discomfort, frustration, and a feeling of never getting enough air. This can profoundly affect exercise tolerance, making physical activity feel like a chore rather than a pleasure. The most significant health implications often arise from its impact on sleep. Moderate to severe nasal valve collapse is a common contributor to loud snoring and can be a key factor in the development or worsening of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). OSA is a serious medical condition where breathing repeatedly stops and starts during sleep, leading to drops in blood oxygen levels and fragmented sleep. Untreated OSA is linked to a host of systemic health problems, including high blood pressure, heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, and increased risk of accidents due to daytime drowsiness. In this context, nasal valve collapse becomes a serious contributing factor to a much larger health issue. So, is it possible to “live with” nasal valve collapse? Technically, yes. Many people do, often for years, by adapting their breathing (e.g., chronic mouth breathing) or by simply tolerating the symptoms. However, “living with it” often means accepting a compromised existence marked by poor sleep, daytime fatigue, reduced physical capacity, and the potential long-term health risks associated with conditions like OSA. The crucial point is that significant improvement is often achievable through appropriate treatment, whether non-surgical aids for milder cases or surgical correction for more severe structural issues. Therefore, while one can live with it, the question becomes should one live with it, especially when effective interventions can restore comfortable breathing, improve sleep, and thereby enhance overall health and well-being. The “seriousness” is thus less about immediate mortality and more about the profound, cumulative toll it takes on vitality and healthspan.

How Does Nostril Collapse Differ From Other Common Nasal Conditions Like a Deviated Septum or Allergies?

Navigating the world of nasal nuisances can be confusing because many conditions share overlapping symptoms, chief among them being that frustrating sensation of a blocked or stuffy nose. However, understanding the distinct characteristics of nostril collapse (or nasal valve collapse) versus other common culprits like a deviated septum or allergies is crucial for pinpointing the right diagnosis and, consequently, the most effective treatment. While all can impede airflow, their underlying mechanisms, tell-tale symptoms, and therapeutic approaches differ significantly. A deviated septum refers to a displacement of the cartilage and bone that divides your two nasal passages; essentially, the internal wall is crooked or off-center. This can physically narrow one or both nasal cavities. Allergies (allergic rhinitis), on the other hand, are an immune system response to airborne allergens like pollen, dust mites, or pet dander, leading to inflammation and swelling of the nasal lining (mucosa), increased mucus production, itching, and sneezing. Nostril/nasal valve collapse, as we’ve discussed, is a structural problem where the sidewall of the nostril or the internal nasal valve area is too weak to withstand the negative pressure of inhalation, causing it to cave inward. While all three can lead to difficulty breathing through the nose, the nuances are key. For instance, allergies often come with a constellation of other symptoms like itchy eyes and throat, and a runny nose, and typically respond to antihistamines or nasal steroid sprays. A deviated septum might cause a more constant, fixed blockage on one side, sometimes associated with headaches or recurrent sinus infections on the affected side. Nasal valve collapse is uniquely characterized by that dynamic inward movement during inspiration, often improved by manually pulling the cheek outward (Cottle maneuver). Teasing apart these conditions requires a careful history, a thorough physical examination by a specialist, and sometimes specific diagnostic tests. It’s also important to note that these conditions are not mutually exclusive; a person can have a deviated septum and nasal valve collapse, or allergies that exacerbate the symptoms of an underlying structural issue. Getting to the root cause, or causes, is the cornerstone of effective relief.

What Is the Difference Between a Deviated Septum and a Nasal Valve Collapse, and How Might They Be Related?

While both a deviated septum and nasal valve collapse can lead to the frustrating symptom of nasal obstruction, they are distinct anatomical problems affecting different parts of the nasal structure and function, though their relationship can be intertwined. A deviated septum specifically refers to the condition where the septum – the internal wall made of cartilage and bone that separates the left and right nasal cavities – is significantly off-center or crooked. Instead of running straight down the middle, it may bow into one side, or have an S-shape, physically narrowing one or both nasal passages. This deviation can be congenital (present from birth) or result from trauma to the nose. The primary symptom is a persistent nasal blockage, often more pronounced on one side, which remains relatively constant regardless of inhalation effort. It can also contribute to snoring, recurrent sinus infections (if it blocks sinus drainage pathways), and sometimes nosebleeds or facial pain.

Nasal valve collapse, in contrast, is a problem of weakness or instability in the sidewalls of the nose, specifically in the nasal valve area (either internal, external, or both). As discussed, the internal nasal valve is the narrowest segment of the nasal airway, formed by the junction of the septum, the upper lateral cartilage, and the inferior turbinate. The external nasal valve is essentially the nostril opening, supported by the alar cartilages. Collapse occurs when these supporting structures are too weak to resist the negative pressure generated during inspiration, causing them to suck inward and obstruct airflow dynamically – meaning the blockage worsens as you try to breathe in.

So, how might these two distinct conditions be related?

- A deviated septum can directly contribute to internal nasal valve collapse. If the septum deviates significantly into the internal nasal valve area on one side, it effectively narrows the angle of that valve. This pre-existing narrowing, combined with even mild weakness of the corresponding upper lateral cartilage, can make that side highly susceptible to collapse during inspiration. The septal deviation essentially “crowds” the valve.

- Trauma that causes a deviated septum can also damage the structures supporting the nasal valve. A significant blow to the nose can simultaneously displace the septum and fracture or destabilize the upper or lower lateral cartilages, leading to both conditions coexisting.

- Previous septal surgery (septoplasty) can sometimes lead to nasal valve issues. If too much septal cartilage is removed, particularly from the dorsal (bridge) or caudal (tip support) aspects, it can weaken the overall structural integrity of the nose, potentially leading to secondary valve collapse or other deformities like a saddle nose.

Therefore, while a deviated septum is a problem of a fixed, misaligned central wall, and nasal valve collapse is a problem of dynamic sidewall weakness, they frequently coexist and can influence each other. A thorough diagnostic evaluation by an ENT specialist or facial plastic surgeon is essential to identify the presence and contribution of each issue, as surgical correction might need to address both for optimal breathing improvement. For instance, a septoplasty might be combined with spreader grafts to both straighten the septum and widen a collapsed internal nasal valve.

How Can I Tell if My Nasal Issues Are Due to a Collapsed Nostril or Are Simply Allergies?

Distinguishing between nasal obstruction caused by a structural issue like a collapsed nostril (nasal valve collapse) and that caused by allergies (allergic rhinitis) can be tricky because the primary symptom – a blocked nose – is common to both. However, by paying close attention to the specific nature of your symptoms and how they respond to certain interventions, you can often gather clues to point you in the right direction, though a professional diagnosis remains essential.

Allergies typically present with a broader cluster of symptoms beyond just blockage. These often include:

- Itching: An itchy nose, eyes, palate, or throat is a hallmark of allergic reactions.

- Sneezing: Frequent, often paroxysmal (sudden and recurrent) bouts of sneezing.

- Runny Nose (Rhinorrhea): Typically a clear, watery discharge, though it can sometimes become thicker.

- Triggers and Timing: Allergic symptoms often flare up in response to specific environmental triggers (e.g., pollen during certain seasons, dust mites in bedding, pet dander) or may be worse at particular times of the day or in specific locations.

- Response to Medications: Symptoms of allergies usually improve, at least partially, with antihistamines (oral or nasal) and nasal corticosteroid sprays, which reduce inflammation and the allergic response.

Nostril/Nasal Valve Collapse, being a structural problem, presents differently:

- Dynamic Blockage: The key characteristic is often a sensation of the nostril caving in or pinching shut, particularly during inspiration (breathing in). The blockage might feel more “mechanical.”

- Visible Collapse: You might actually see the side of your nostril suck inward when you inhale deeply, especially if you look in a mirror.

- Cottle Maneuver Relief: Gently pulling your cheek outward on the affected side (the Cottle maneuver) often provides immediate, noticeable improvement in airflow if valve collapse is present. This maneuver is unlikely to significantly help blockage caused purely by allergic mucosal swelling.

- Lack of Itching/Sneezing: While someone with valve collapse can also have allergies, the collapse itself doesn’t cause itching or sneezing.

- Limited Response to Allergy Medications: While allergy medications might reduce any coexisting mucosal swelling (which can make the collapse feel worse), they won’t fix the underlying structural weakness. The mechanical aspect of the collapse will persist.

It’s also important to consider that these conditions can coexist. You might have an underlying tendency for your nasal valve to collapse, which becomes much more problematic when your allergies flare up and cause the nasal lining to swell, further narrowing an already compromised airway. In such cases, treating the allergies can provide some relief by reducing the swelling, but the underlying structural issue might still require attention if symptoms persist.

If you suspect nasal valve collapse, noting a positive Cottle maneuver and observing visible nostril narrowing on inhalation are strong indicators to discuss with your doctor. They can perform a thorough examination to differentiate or confirm coexisting conditions.

What Is a Saddle Nose Deformity, and How Is It Connected to Nostril Collapse or Nasal Support Loss?

A saddle nose deformity is a distinct and often noticeable condition characterized by a visible depression or concavity along the bridge of the nose, specifically in the middle third (cartilaginous dorsum). The name derives from its appearance, resembling the curve of a riding saddle. This deformity is not merely a cosmetic issue; it signifies a significant loss of structural support in a critical area of the nose, which almost invariably has profound implications for nasal function, including a strong association with severe nostril and internal nasal valve collapse. The primary cause of a saddle nose is the loss or weakening of dorsal septal support. The nasal septum, particularly its upper cartilaginous portion, acts like the central tent pole supporting the nasal bridge. If this support is compromised, the bridge collapses downward, creating the characteristic “saddled” appearance. Several factors can lead to this critical loss of support:

- Severe Nasal Trauma: A major blow to the nose can shatter the septal cartilage or lead to a septal hematoma (blood clot within the septum) that, if not drained promptly, can destroy the cartilage due to pressure necrosis (tissue death from lack of blood supply).

- Over-aggressive Previous Nasal Surgery: Excessive removal of septal cartilage during a septoplasty or rhinoplasty, especially from the dorsal or caudal (tip-supporting) aspects, can critically weaken the nose’s framework, leading to a delayed or immediate saddle deformity.

- Certain Medical Conditions: Autoimmune diseases like granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly Wegener’s granulomatosis) or relapsing polychondritis can cause inflammation and destruction of nasal cartilage. Infections like syphilis or advanced intranasal drug use (e.g., cocaine) can also erode septal support.

The connection to nostril collapse and nasal support loss is direct and severe. When the dorsal septal support collapses to form a saddle nose, the upper lateral cartilages, which attach to the septum and form a crucial part of the internal nasal valve, also lose their support and often collapse inward. This results in severe internal nasal valve collapse, leading to significant breathing obstruction. Furthermore, the overall loss of structural integrity can destabilize the entire nasal tip and alar structures, contributing to external nasal valve collapse (nostril collapse) as well. In essence, a saddle nose deformity is a manifestation of major nasal structural collapse involving the bridge. While nasal valve collapse can occur independently without such a dramatic external deformity (e.g., due to isolated weakness of the alar cartilages), the presence of a saddle nose almost guarantees significant accompanying internal and often external nasal valve compromise due to the widespread loss of foundational support. Repairing a saddle nose deformity is a complex reconstructive challenge, typically requiring substantial cartilage grafting (often from the rib or ear) to rebuild the nasal bridge and restore both aesthetic contour and, critically, functional airflow by re-establishing nasal valve patency.

How Long Does It Typically Take for a Nasal Valve Collapse to Heal After Treatment?

The healing timeline following treatment for nasal valve collapse depends significantly on the type of intervention undertaken. Non-surgical approaches offer immediate but temporary effects, while surgical repairs involve a more extended, phased recovery process leading to long-term structural changes. For non-surgical treatments like external nasal dilator strips or internal nasal stents, the effect is immediate upon application. You’ll likely notice improved airflow as soon as the dilator is correctly positioned. However, this isn’t “healing” in the traditional sense; it’s a mechanical splinting effect that lasts only as long as the device is in use. There’s no structural recovery period involved because the underlying anatomy isn’t altered.

For surgical treatments, which aim to permanently correct the structural issues, the healing journey is more involved and unfolds over weeks and months:

- Initial Healing Phase (First 1-3 weeks): This is characterized by the most noticeable swelling, bruising (especially if bone work or extensive grafting was involved, as in a full rhinoplasty), and discomfort. You may have an external splint or cast on your nose, and possibly internal splints or packing for the first few days to a week. Breathing through the nose might initially be worse than before surgery due to internal swelling and any packing. Pain is usually manageable with prescribed medication. Most significant bruising and swelling typically subside within 2-3 weeks.

- Return to Most Normal Activities (2-6 weeks): As the initial swelling decreases, you’ll start to notice an improvement in nasal airflow. You can usually return to work or school within 1-2 weeks, depending on the extent of the surgery and the nature of your activities. Strenuous exercise, heavy lifting, and activities that risk impact to the nose are generally restricted for about 4-6 weeks, or as advised by your surgeon.

- Significant Improvement in Breathing (Weeks to Months): You’ll likely experience a noticeable and progressive improvement in your ability to breathe through your nose during this period. While much of the gross swelling is gone, subtle internal swelling can persist for much longer. The LATERA® implant, if used, is providing support while the body begins its tissue remodeling process around it. Cartilage grafts are starting to integrate with the surrounding tissues.

- Final Results and Full Tissue Maturation (6 months to a year, or even longer): This is the phase where the last vestiges of subtle swelling resolve, and the tissues fully mature and settle into their new, surgically enhanced positions. For complex functional rhinoplasties involving significant cartilage grafting, it can take 12-18 months to see the absolute final aesthetic and functional outcome. By this point, cartilage grafts should be well-integrated, and the structural support established by the surgery should be stable and providing lasting improvement in nasal airflow.

It’s crucial to follow your surgeon’s post-operative instructions meticulously to ensure optimal healing. Patience is also key, as the full benefits of surgical repair for nasal valve collapse unfold gradually over time. Regular follow-up appointments will allow your surgeon to monitor your progress and address any concerns.

How Common Is a Collapsed Nostril or General Nasal Collapse Among the Population?

Pinpointing exact prevalence figures for nostril collapse or nasal valve collapse across the general population can be challenging, as it’s a condition that often goes underdiagnosed or is misattributed to other common nasal issues like chronic allergies or “sinus problems.” However, within the specialized field of otolaryngology (ENT) and facial plastic surgery, it is recognized as a surprisingly common and significant cause of nasal airway obstruction in adults. While you might not hear it discussed as frequently as a deviated septum, its impact on breathing is substantial, and specialists are increasingly aware of its prevalence. Studies focusing on patients presenting to ENT clinics with complaints of nasal obstruction often find that a considerable percentage have some degree of nasal valve dysfunction, either as the primary cause of their symptoms or as a contributing factor alongside other issues like septal deviation or turbinate hypertrophy. Some experts suggest that nasal valve collapse might be implicated in as many as 10-20% of cases of chronic nasal obstruction, and potentially even higher in specific patient populations. For instance, individuals who have undergone previous rhinoplasty are at a higher risk. Estimates vary, but some literature suggests that a notable portion of patients seeking revision rhinoplasty do so because of breathing problems related to iatrogenic (surgically induced) nasal valve collapse from their initial procedure. Similarly, those who have experienced significant nasal trauma are more susceptible. The aging population also sees an increased incidence, as natural weakening of cartilaginous support and soft tissues can lead to gradual onset of nasal valve insufficiency. The condition can affect people of all ages and ethnicities, although certain nasal anatomies (e.g., narrow noses, or noses with inherently delicate cartilage) might be more predisposed. The growing awareness among both patients and medical professionals, coupled with improved diagnostic techniques, is leading to more frequent identification of nasal valve collapse. So, while it might not be a term you hear every day, the reality is that a collapsed nostril or compromised nasal valve is a prevalent issue quietly affecting the breathing and quality of life for a significant number of people, many of whom could benefit from targeted diagnosis and treatment.

How Much Does It Generally Cost to Fix a Collapsed Nostril?

The cost associated with fixing a collapsed nostril or nasal valve can vary dramatically, making it difficult to provide a single, universally applicable figure. A multitude of factors come into play, influencing the final bill for restoring comfortable nasal breathing. The most significant determinant is the specific procedure performed. A minimally invasive option like the LATERA® implant procedure, especially if done in an office setting, will generally be less expensive than a comprehensive functional rhinoplasty requiring extensive cartilage grafting and performed in a hospital or accredited surgical center under general anesthesia. A septoplasty combined with spreader grafts for internal valve collapse will fall somewhere in between. The surgeon’s fees are another major component, varying based on their experience, specialty (e.g., a board-certified facial plastic surgeon or otolaryngologist with expertise in nasal reconstruction), reputation, and the complexity of the individual case. Geographic location also plays a substantial role; procedures tend to cost more in major metropolitan areas with higher overheads compared to smaller towns or regions with a lower cost of living. Furthermore, anesthesia fees (charged by the anesthesiologist) and facility fees (charged by the hospital or surgical center for the use of their operating room, staff, and equipment) contribute significantly to the overall expense, particularly for procedures requiring general anesthesia. One of the most critical questions for patients is whether insurance will cover the procedure. If the nasal valve collapse is well-documented as causing medically significant functional breathing impairment, insurance companies may cover the portions of the surgery deemed medically necessary to correct this functional deficit. This could include procedures like septoplasty, turbinate reduction, placement of spreader grafts, or the LATERA implant. However, if any part of the procedure is considered purely cosmetic (e.g., altering the shape of the nose for aesthetic reasons without a functional benefit), that portion will typically not be covered by insurance and will be an out-of-pocket expense for the patient. Obtaining prior authorization from the insurance company is crucial. It’s highly advisable for patients to have a detailed consultation with their chosen surgeon to understand the recommended procedure, the breakdown of costs (surgeon’s fee, anesthesia, facility), and to discuss insurance coverage and potential out-of-pocket expenses thoroughly before committing to surgery. Many surgical practices offer financing options to help manage the costs.

Frequently Asked Questions About Nostril Collapse

Navigating the complexities of nostril collapse and nasal valve issues often brings a flurry of questions to the forefront. It’s a topic that directly impacts a fundamental human need – the ability to breathe easily – yet it’s often shrouded in medical terminology that can feel overwhelming. This section aims to distill some of the most common queries into clear, understandable answers, empowering you with the knowledge to better comprehend this condition. We’ll revisit key aspects such as precisely what nostril collapse entails and its far-reaching effects on daily life, especially sleep and respiratory comfort. We will also re-examine the diverse array of factors that can lead to this structural compromise, from accidental injuries to the subtle yet persistent effects of aging or the unintended consequences of previous surgical interventions. Furthermore, we’ll touch upon the diagnostic journey – how medical professionals pinpoint this elusive condition and what signs might suggest its presence even before you step into a doctor’s office. Understanding the general principles of repair, both surgical and non-surgical, is another area of frequent inquiry, as patients understandably want to know the spectrum of available solutions. Finally, we will consider the implications of leaving nostril collapse unaddressed, exploring how this seemingly isolated issue can ripple outwards, affecting long-term health and overall well-being. Our goal here is to provide concise, accessible information, reinforcing the core concepts discussed throughout this guide, so you feel more informed and prepared to discuss your concerns with a healthcare provider. This isn’t just about understanding a medical condition; it’s about reclaiming your comfort and your breath, one informed step at a time. Let’s delve into these frequently asked questions to bring further clarity to the world of nostril collapse.

What Exactly Is Nostril Collapse, and How Can It Affect Your Breathing and Sleep?

Nostril collapse, more formally known as nasal valve collapse, is a condition where the sidewall of the nostril (the ala) or the internal nasal valve (the narrowest part of the nasal airway located further inside) lacks sufficient structural support and is drawn inward during inhalation. Imagine trying to sip a drink through a very soft straw; as you inhale, the straw collapses, obstructing the flow. A similar dynamic occurs in the nose. The nasal valve area is critical for regulating airflow. If its cartilaginous framework is weak, damaged, or malformed, the negative pressure created when you breathe in can overcome its ability to stay open, leading to a partial or complete blockage of the nasal passage. This isn’t just a minor inconvenience; it can profoundly affect your ability to breathe comfortably and efficiently through your nose. You might experience a persistent sensation of nasal congestion, as if you always have a cold, or find that you have to exert significant effort just to draw air in, especially during physical activity. This can lead to chronic mouth breathing, which bypasses the nose’s natural filtration and humidification system, potentially causing dry mouth, sore throats, and an increased susceptibility to infections. The impact on sleep quality can be particularly severe. The struggle for adequate airflow during the night often manifests as loud snoring, as the air forces its way through a narrowed passage. It can also lead to frequent awakenings, restless sleep, and daytime fatigue. In more significant cases, nostril collapse can be a contributing factor to obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), a serious condition where breathing repeatedly stops and starts during sleep, depriving the body of oxygen and disrupting restorative sleep cycles. This can have long-term consequences for cardiovascular health and cognitive function. Therefore, what might seem like a simple “stuffy nose” due to nostril collapse can, in reality, be a gateway to a host of issues affecting your breathing, your sleep, and your overall energy levels and well-being. Understanding this connection is the first step towards seeking effective solutions and reclaiming the effortless breath that is so vital to a healthy life.

What Are the Primary Reasons and Underlying Factors That Cause a Nostril or Nasal Cartilage to Collapse?