Table of Contents

ToggleKey Takeaways

- Molars are the **largest and strongest teeth** at the back of your mouth, essential for grinding food.

- There are two sets: **primary molars** (baby teeth, 8 total) and **permanent molars** (adult teeth, typically 12 total, including wisdom teeth).

- Permanent molars erupt sequentially, starting around age **6** (first molars), then **12** (second molars), and **17-25** (wisdom teeth/third molars).

- Molar teething in babies can cause _fussiness, drooling, and swollen gums_, but **not** systemic illness like high fever.

- Molar pain is common, often caused by _decay, infection, cracks, or impaction_, and **requires professional dental diagnosis and treatment**.

- Permanent molars are **not meant to fall out**; losing one indicates a serious problem and often requires replacement.

- Wisdom teeth frequently cause problems due to _lack of space_ and are often **extracted**.

- Diligent home care and **regular dental check-ups** are crucial for maintaining molar health.

Understanding Molar Teeth: Anatomy, Location, and Function – Delving into the Structural Brilliance and Mechanical Prowess of Your Back Teeth, the Unsung Heroes Responsible for Preparing Every Morsel of Food for Digestion, a Complex Biological Design Perfected Over Millennia for Maximum Efficiency.

Positioned strategically at the posterior (back) of both the upper (maxillary) and lower (mandibular) jaws, molars are the largest and strongest teeth in your mouth, built for heavy-duty work. Think of them as nature’s built-in mortar and pestle system, designed to withstand the significant forces generated during mastication (chewing). Their location provides leverage and proximity to the jaw joint, facilitating the powerful grinding motion required to break down tough fibres and dense foods. Each molar is a marvel of biological engineering, composed of several key anatomical features. At the visible top, protruding into the oral cavity, is the **crown**, typically square or rectangular in shape. Unlike the sharp, single-pointed cusps of canines or the two cusps of premolars, molar crowns feature multiple prominent bumps or ridges called **cusps**. These cusps interlock with the opposing molars in the other jaw, creating the rough, uneven surface necessary for effective grinding. Beneath the gum line, hidden from view, are the tooth’s **roots**. Permanent molars are distinguished by having multiple roots – typically two or three in upper molars and two in lower molars, though variations exist. These roots are longer and more numerous than those of front teeth, providing a far more stable anchor within the jawbone, crucial for resisting the immense pressures of chewing. The primary function of molars is unequivocally **grinding food for digestion**. As food enters the mouth, the front teeth (incisors and canines) are primarily for cutting and tearing, while the premolars assist in initial crushing. The molars then take over, using their broad surfaces and interlocking cusps in a powerful, side-to-side and up-and-down motion to reduce food to a fine pulp, increasing its surface area for salivary enzymes to begin the digestive process before it’s swallowed. This efficiency is critical for nutrient absorption. Dentally speaking, the term ‘Dens molaris’ serves as the Latin designation for the molar tooth, a nod to its historical and anatomical recognition within the scientific community. Understanding this fundamental structure and function is the first step in appreciating the indispensable role molars play in overall health, far beyond just filling space in the back of your mouth. Their complex architecture not only enables efficient chewing but also contributes significantly to maintaining the vertical dimension of your bite and the structural integrity of your jaw. Any compromise to a molar’s health can have ripple effects throughout the entire oral system.

Which teeth are molar? Pinpointing the Powerhouse Grinders Within Your Dental Arch, From the First Eruptions of Childhood to the Arrival of the Notorious Wisdom Teeth, Understanding Their Specific Positions and Quantity in Both Primary and Permanent Dentitions.

Within the human mouth, a specific class of teeth is designated as molars, identifiable by their position, shape, and function. These are the teeth furthest back in the jaw, behind the premolars (or bicuspids). In the **permanent dentition** of an adult, there are typically twelve molars in total: three in each quadrant (upper right, upper left, lower right, lower left). These are sequentially named based on their eruption order and position relative to the front of the mouth: the **first molars**, the **second molars**, and the **third molars**, the latter commonly known as **wisdom teeth**. The first molars are closest to the front of the mouth, positioned just behind the premolars (which themselves sit behind the canines and incisors). The second molars are located directly behind the first molars, and the third molars (wisdom teeth) are situated at the very back of the mouth, behind the second molars. In **primary dentition**, the temporary set of teeth present in children (often called “baby teeth”), the composition is slightly different. Children have a total of twenty primary teeth, which include eight molars: two in each quadrant. These are referred to simply as the **first primary molars** and **second primary molars**. There are no primary teeth that correspond to premolars or wisdom teeth. As a child grows, these primary molars eventually become loose and fall out, but they are *not* replaced by permanent molars. Instead, the space vacated by the primary molars is later occupied by the permanent premolars. The permanent molars, including the first, second, and third sets, erupt *behind* the position of the primary molars, extending the dental arch further back into the jaw as the skull grows. Thus, identifying which teeth are molars is a matter of recognizing their characteristic multi-cusped crowns and their position at the back of the mouth, a placement fundamental to their role as the primary grinding apparatus. They are the most distal teeth in both sets, crucial for the final stage of food breakdown before swallowing, clearly distinguishing them from the incisors, canines, and premolars located anteriorly.

What are the 3 molar teeth? Identifying the Distinct Generations of Permanent Molars and Their Respective Arrival Times, Understanding the Sequential Development and Placement of These Key Grinding Units Within the Maturing Oral Cavity.

In the realm of permanent teeth, the term “the 3 molar teeth” specifically refers to the three distinct sets of molars that typically erupt in each quadrant of the mouth, resulting in a potential total of twelve permanent molars. These are the **first molars**, the **second molars**, and the **third molars**. Each set appears at a different, albeit somewhat variable, stage of development, contributing sequentially to the complete adult dentition. The **first molars**, often referred to as the “six-year molars” because of their approximate eruption age, are usually the very first permanent teeth to emerge in the mouth, appearing behind the last primary molars. They do not replace any primary teeth. These are arguably the most critical molars, serving as the foundational pillars of the adult bite and playing a vital role in jaw development and alignment from an early age. Their early arrival and prominent position make them indispensable for efficient chewing throughout childhood and adulthood. Following the first molars, the **second molars** make their appearance. These are commonly dubbed the “twelve-year molars,” as they typically erupt around this age, positioning themselves directly behind the first molars. Like the first molars, they do not replace any primary teeth but rather extend the dental arch further back. They reinforce the grinding capacity initiated by the first molars and are essential components of the functional chewing surface. Finally, at the very back of the mouth, come the **third molars**. These are famously known as **wisdom teeth**. They are the last teeth to erupt, usually appearing much later than the others, typically between the ages of 17 and 25. Their eruption timing is highly variable, and unlike the first two sets, the third molars are often problematic due to lack of space in the jaw, leading to impaction (failure to erupt properly) or misalignment, frequently necessitating their removal. Thus, the three types of permanent molars – first, second, and third – represent a chronological and positional progression of grinding teeth, each contributing in its own way to the mature dental structure, with the wisdom teeth often posing unique challenges due to their late and sometimes awkward arrival.

Types of Molars: Primary vs. Permanent – Distinguishing Between the Temporary Grinders of Childhood and the Enduring Workhorses of Adulthood, Understanding Their Different Lifespans, Roles, and the Unique Transitional Period As One Set Is Replaced by Another (and Different) Set.

Molars appear in two distinct sets throughout a person’s life: the **primary molars** (part of the “baby teeth” or deciduous dentition) and the **permanent molars** (part of the adult dentition). While both types share the fundamental function of grinding food, they differ significantly in number, lifespan, and replacement pattern. Children typically develop eight **primary molars** – two in each of the four quadrants of the mouth. These are the first primary molars and the second primary molars. They begin erupting in infancy and serve as the main grinding teeth during the crucial early years of solid food consumption. Primary molars are smaller than their permanent counterparts and have a whiter appearance. They also tend to have more flared roots, which helps them hold their position but also allows the developing permanent teeth beneath them to grow into place. Primary molars play a vital role not only in chewing but also in maintaining space for the permanent teeth that will eventually replace them. Crucially, the primary molars are **shed** (fall out) as a child grows, typically between the ages of 10 and 12. However, they are *not* replaced by permanent molars. Instead, the space vacated by the primary molars is taken up by the **permanent premolars** (bicuspids), which erupt around the same time. The **permanent molars**, on the other hand, are a completely different set of teeth that begin erupting *behind* the primary teeth and continue to push the dental arch backwards as the jaw grows. As discussed, there are usually twelve **permanent molars** – the first, second, and third molars in each quadrant. These are larger, stronger, and designed to last a lifetime, assuming proper care. The key distinction in replacement is this: primary molars are replaced by permanent *premolars*, while permanent molars erupt into previously empty space at the back of the mouth. Understanding this difference is critical for parents tracking their child’s dental development and for adults appreciating the permanent nature of their molars once they have erupted. The transition from primary to permanent dentition is a complex process of shedding, eruption, and jaw growth, orchestrated to establish the full adult complement of 32 teeth, with the permanent molars serving as the indispensable anchors of the final bite.

Molar Eruption Timing: When Do Molars Come In? Navigating the Developmental Milestones of These Crucial Teeth, From Their Initial Appearance in Childhood to the Often-Anticipated (and Sometimes Treacherous) Arrival of Wisdom Teeth in Early Adulthood, Understanding the Typical Chronological Sequence.

The emergence of molar teeth is a significant marker in dental development, occurring over several distinct phases from infancy through early adulthood. Unlike the front teeth, which often appear relatively quickly during a baby’s first year, molars arrive later and their eruption can be a more prolonged and sometimes uncomfortable process. The timing follows a general, predictable sequence for both primary and permanent sets, though individual variations are common. For **primary molars**, the first ones (first primary molars) usually make their debut between 13 and 19 months of age, often causing noticeable teething symptoms. The second primary molars, located further back, typically erupt between 25 and 33 months. These primary molars remain in place, serving their chewing function, until it’s time for them to be naturally shed to make way for permanent teeth, which happens much later in childhood. The eruption of **permanent molars** begins significantly later and extends over a longer period. The sequence starts with the first permanent molars, followed by the second, and finally the third (wisdom teeth). Understanding these timelines is crucial for parents monitoring their child’s dental health and for individuals anticipating the arrival of their own wisdom teeth. While these are average age ranges, factors like genetics, overall health, and nutrition can influence the exact timing. Dentists use these general timelines to assess normal development, but minor deviations are rarely a cause for concern unless accompanied by other issues. The eruption process for permanent molars involves the teeth slowly pushing through the gum tissue, a process that can take several months per tooth. Awareness of these typical timeframes allows for proactive dental care, such as anticipating teething discomfort in young children or discussing potential wisdom tooth issues in teenagers and young adults.

What age do molars come in? Providing a Closer Look at the Typical Age Ranges for the Eruption of Permanent Molars, Offering Parents and Individuals a Benchmark for Dental Development and Anticipating the Arrival of These Essential Back Teeth.

Pinpointing the exact moment a tooth will erupt is impossible, as individual development varies, but there are well-established average age ranges for the appearance of permanent molars. These benchmarks provide a useful guide for parents, dental professionals, and individuals tracking their dental milestones. The **first permanent molars** are typically the earliest to erupt among the permanent teeth, often appearing around **6 years old**. Because they arrive relatively early and don’t replace any primary teeth, they are frequently nicknamed the “six-year molars.” Their eruption behind the last primary molars expands the dental arch and establishes the foundation for the adult bite. Next in line are the **second permanent molars**, which usually erupt around **12 years old**, earning them the common moniker “twelve-year molars.” They position themselves directly behind the first molars, further solidifying the chewing surface and extending the dental arch. These two sets of molars are generally expected to erupt without significant complications, provided there is sufficient space. The final set of permanent molars, the **third molars** or **wisdom teeth**, have the widest and latest eruption window, typically emerging between the ages of **17 and 25**. This wide range reflects the variability in jaw growth and development among individuals. In many cases, particularly in modern populations, there isn’t enough space at the very back of the jaw for wisdom teeth to erupt fully and properly, leading to impaction or other issues. It’s important to remember that these are just averages. Some children may get their six-year molars slightly earlier, and some adults may experience wisdom tooth eruption or issues well into their late twenties or even thirties. However, knowing these typical age ranges allows for timely dental check-ups to monitor development, catch potential problems early, and ensure that these crucial teeth are coming in correctly. Regular visits allow dentists to track eruption patterns using clinical examination and X-rays, ensuring the developmental process is on the right track.

When do molars come in? Getting Permanent Teeth – Describing the Broader Process of Permanent Tooth Eruption, Focusing on the Molars’ Role in Expanding the Dental Arch and Establishing the Adult Bite, and Contrasting This With the Shedding of Primary Teeth.

The arrival of permanent teeth is a gradual, complex process that unfolds over several years, beginning typically around age 6 and continuing into early adulthood. While the shedding of primary teeth and their replacement by permanent incisors, canines, and premolars is a noticeable event, the eruption of permanent molars is equally, if not more, significant for the long-term structure and function of the adult mouth. Unlike the permanent teeth that replace primary teeth, the permanent molars **do not replace any pre-existing teeth**. Instead, they erupt behind the primary teeth (and later, behind the permanent premolars), effectively increasing the number of teeth in the mouth and extending the dental arch further back into the growing jaw. This process starts with the first permanent molars around age 6, followed by the second permanent molars around age 12, and finally the third molars (wisdom teeth) later in the teens or early twenties. As these molars emerge, they are guided into position by the surrounding jawbone and the pressure from opposing teeth. Their eruption helps to increase the overall surface area available for chewing, which is essential as a child grows and requires more efficient food processing. This extension of the dental arch is a critical component of jaw development and helps to establish the correct bite alignment for the permanent dentition. In contrast, the process involving primary teeth is one of replacement. Primary teeth become loose as their roots resorb (dissolve), pushed out by the permanent teeth developing beneath them. Primary incisors are replaced by permanent incisors, primary canines by permanent canines, and primary molars by permanent premolars. The permanent molars simply add to the total number of teeth, taking up newly available space at the back of the jaw. Understanding this distinction – replacement for anterior teeth and premolars vs. addition for permanent molars – highlights the unique developmental pathway of molars and their indispensable role in forming the complete and functional adult dentition, designed for a lifetime of chewing efficiency, assuming they erupt correctly and are properly cared for.

What age do wisdom teeth come in? Focusing Specifically on the Latest Arrivals in the Molar Family, the Third Molars, Discussing Their Highly Variable Eruption Timeline and Why They Are Often Associated With Issues and Late-Stage Development.

The wisdom teeth, scientifically known as the third molars, hold the distinction of being the final teeth to erupt in the human mouth, if they erupt at all. Their typical arrival window is considerably later than other permanent teeth, generally falling between the ages of **17 and 25**. This timeframe coincides with a period in life often associated with gaining wisdom, hence the common name. However, their late eruption is often a source of complications rather than enlightenment for many individuals. Unlike the first and second molars, which usually have ample space to emerge into a developing jaw, the jawbone’s growth is often complete or nearing completion by the time the third molars are ready to erupt. In many people, particularly with modern diets and potentially smaller jaws compared to our ancestors, there simply isn’t enough room at the very back of the dental arch for these teeth to emerge fully and properly. This lack of space can lead to various issues, most notably **impaction**. An impacted wisdom tooth is one that is unable to fully erupt through the gum line, becoming trapped or growing in an awkward direction (sideways, angled, or only partially emerged). Impaction can cause pain, swelling, infection, damage to adjacent teeth, or the formation of cysts. Even if they do erupt, they are located so far back in the mouth that they are often difficult to clean effectively, making them prone to cavities and gum disease. While the 17-25 age range is most common, it’s not a strict rule. Some individuals may see their wisdom teeth emerge slightly earlier, while others might experience issues or partial eruption well into their late twenties or even thirties. A significant number of people may never develop wisdom teeth at all (a condition called agenesis), or the teeth may remain fully embedded in the jawbone without causing problems, never erupting into the mouth. Regular dental check-ups during the late teenage and early adult years are crucial for monitoring the development and position of wisdom teeth and determining if proactive management, such as extraction, is necessary to prevent future complications.

Can I get wisdom teeth at 40? Addressing the Possibility of Late-Stage Eruption or Issues Related to Third Molars Occurring Well Beyond the Typical Age Range, Explaining Potential Scenarios That Might Lead to Wisdom Tooth Problems in Middle Adulthood.

While the most common age range for wisdom tooth eruption and related issues is between 17 and 25, the possibility of problems arising with third molars later in life, even at age 40 or beyond, is absolutely real. It’s less frequent than in younger individuals, but not impossible. Several scenarios can lead to wisdom tooth issues emerging or becoming noticeable in middle adulthood. One possibility is that the wisdom teeth developed but never fully erupted, remaining impacted within the jawbone. Over time, changes in the mouth or jaw, such as slight tooth shifting due to aging, gum recession, or even changes in bite alignment, can sometimes cause a previously stable, impacted wisdom tooth to start pressing against surrounding structures, including the adjacent second molar or nerve. This movement or pressure can trigger pain, inflammation, or increase the risk of infection around the partially erupted or impacted tooth. Another scenario involves a wisdom tooth that may have partially erupted years earlier without causing significant problems at the time. Over decades, this partially emerged tooth can accumulate plaque and bacteria much more easily than fully erupted teeth because it’s harder to clean properly at the very back of the mouth. This can lead to chronic low-grade infection, gum inflammation (pericoronitis), or deep cavities, eventually causing noticeable pain, swelling, or decay that necessitates evaluation and potentially extraction in middle age. Furthermore, cysts or tumours can rarely develop around the crown of an impacted tooth, which may grow slowly over many years before causing symptoms that require intervention. Therefore, while reaching 40 might feel like you’ve safely navigated the wisdom tooth years, it’s important to remain aware that previously dormant issues can sometimes flare up, or new problems like decay or infection can develop in existing, difficult-to-clean third molars. If you experience pain, swelling, or discomfort in the back of your mouth at any age, it’s crucial to consult a dentist to determine the underlying cause and appropriate treatment.

Molar Teething Symptoms and How to Manage Them – Guiding Parents and Caregivers Through the Often-Challenging Period When These Larger Back Teeth Emerge in Infants and Young Children, Offering Practical Advice for Comfort and Relief During Developmental Milestones.

Teething is a universal experience in infancy and early childhood, marking the exciting, yet often uncomfortable, milestone of teeth emerging through the gums. While the eruption of front teeth can cause fussiness and discomfort, the arrival of molars – both the first and second primary sets – can sometimes be particularly challenging. This is primarily because molars are significantly larger and have broader, less sharp surfaces compared to incisors or canines. As these larger, blunt teeth push through the gum tissue, they can cause more pressure and a wider area of irritation and swelling. The process can take several weeks or even months for a single molar to fully erupt. Parents often notice their child experiencing increased distress during molar teething periods compared to when the front teeth came in. Understanding the typical symptoms and having a repertoire of management strategies can make this phase much more bearable for both the child and the caregiver. While teething is a natural process, severe, unmanageable pain or symptoms that resemble illness should always prompt consultation with a healthcare professional to rule out other causes. The goal is to alleviate discomfort and support the child through this temporary phase of growth and development. Molar teething is a normal, albeit sometimes intense, part of early childhood; knowing what to expect and how to respond effectively empowers parents to provide the best possible care and comfort for their little ones as their crucial grinding teeth make their way into the world, setting the stage for future eating habits and overall dental health.

What are the symptoms of teething in molars? Identifying the Common Signs That Indicate Your Little One’s Molar Teeth Are Making Their Way Through, Helping Parents Distinguish Teething Discomfort From Other Potential Issues and Provide Targeted Relief.

Recognizing the signs of molar teething can help parents understand what their child is experiencing and offer appropriate comfort. While symptoms can vary in intensity from child to child, several common indicators point towards molars pushing through the gums. One of the most frequent signs is increased **fussiness and irritability**. Children may seem more agitated, cry more often, or have difficulty settling, particularly at night, as the pressure and discomfort in their gums intensify. You’ll also likely notice a significant increase in **drooling**, often soaking clothes and potentially leading to a rash around the mouth or chin due to constant moisture. Children experiencing molar teething often feel an urge to chew or gnaw on anything they can get their hands on – toys, blankets, fingers, or teething rings – using the counter-pressure to soothe their sore gums. Upon visual inspection, the gums in the back of the mouth where the molars are developing may appear **swollen, red, or tender** to the touch. Sometimes, you might even see a slight bulge or a whitish spot on the gum line as the tooth gets closer to erupting. Sleep disruption is also a common symptom, with children waking more frequently at night due to discomfort. Less common but still possible signs include rubbing their ears or cheeks (due to referred pain), a slight decrease in appetite, or mild temperature elevation, though high fevers are typically *not* caused by teething alone. It’s important to remember that while these symptoms are characteristic of teething, they can also overlap with signs of minor illnesses. If you are concerned about the severity or duration of symptoms, or if your child develops a high fever, vomiting, or diarrhea, it’s always best to consult with a pediatrician to rule out other health issues. Focusing on comfort measures for the specific signs observed can significantly help ease the molar teething journey for both parent and child.

Can molars make baby sick? Clarifying the Nuance Between Teething Discomfort and Actual Illness, Dispelling Myths While Advising Caution and Professional Consultation When Symptoms Suggest Something More Than Just Emerging Teeth.

This is a perennially debated topic among parents and caregivers: can teething, particularly the eruption of large molars, actually make a baby sick? The consensus among medical and dental professionals is that **teething itself does not cause systemic illness** like high fever, diarrhea, vomiting, or significant respiratory symptoms. While the discomfort associated with molar teething can certainly make a baby *seem* unwell – leading to fussiness, changes in sleep and eating patterns, and increased drooling – these are generally localized symptoms related to gum irritation and pressure. The myth that teething causes fever or diarrhea is likely due to the fact that babies around the typical age for teething (6-18 months) are also developing their immune systems, exploring the world by putting objects in their mouths (which can introduce germs), and potentially being exposed to common childhood illnesses in daycare settings. Therefore, a baby might coincidentally develop a fever or other symptoms of illness *at the same time* they are teething, but the teething isn’t the direct cause of the illness. Increased drooling during teething can sometimes lead to a mild cough or gagging, or the extra saliva passing through the digestive system might slightly loosen stools, but this is distinct from true diarrhea caused by infection. Similarly, while the body temperature might slightly elevate due to stress or inflammation around the gums, teething does not cause a high fever (generally considered 101°F or 38.3°C and above). The takeaway is crucial: while teething is uncomfortable, if your baby develops symptoms like a high fever, vomiting, diarrhea, significant congestion, or seems genuinely unwell beyond just being fussy and irritable, do not attribute it solely to teething. These symptoms warrant evaluation by a pediatrician to diagnose and treat any underlying infection or illness. Providing comfort for teething pain is appropriate, but recognizing the signs that require medical attention is paramount for your child’s health and safety.

How bad is molar teething? Providing Context on the Potential Intensity of Discomfort During Molar Eruption Compared to Other Teeth and Offering Reassurance Along With Effective Strategies to Help Alleviate the Challenges for Both Child and Parent.

Let’s be frank: molar teething can sometimes feel pretty bad, both for the baby experiencing it and the parents trying to soothe them. While the eruption of any tooth can cause discomfort, molars are often cited as being among the most challenging teeth to cut. There are a few key reasons for this. Firstly, molars are significantly **larger** than incisors or canines. The broader surface area pushing through the gum tissue can create more widespread pressure and inflammation compared to a single, relatively sharp incisor edge. Secondly, molars typically have **multiple roots**, which need to anchor securely into the jawbone as the tooth erupts. The complex structure beneath the surface contributes to the overall sensation of pressure and potential pain. Furthermore, they are located at the **back of the mouth**, making them harder to reach and perhaps contributing to a feeling of deeper discomfort or even referred pain to the jaw or ear. The period leading up to a molar breaking through the gum can involve significant swelling and tenderness. However, “how bad” it is varies greatly from one child to another. Some babies seem to barely notice, while others experience prolonged periods of intense fussiness, poor sleep, and reduced appetite. While it can be difficult when your child is clearly in pain, it’s important to remember that molar teething is a **temporary phase**. The intense discomfort usually subsides once the tooth has fully emerged. Parents can employ various strategies to help. Offering safe chewing objects (chilled, not frozen, teething rings, or clean washcloths) provides soothing counter-pressure. Gently rubbing the gums with a clean finger can also offer relief. Over-the-counter remedies like infant acetaminophen or ibuprofen (used according to dosage instructions and age guidelines) can help manage pain and inflammation, but consult a pediatrician before administering medication. Ultimately, patience, comfort, and recognizing that this is a normal part of development are key. While challenging, the discomfort is a sign their body is growing and developing these essential chewing tools.

How do I know if my molars are growing? Identifying the Signs and Sensations Associated With Molar Eruption, Particularly Relevant for Teenagers and Young Adults Experiencing the Arrival or Movement of Their Third Molars (Wisdom Teeth), and What to Look and Feel For.

For teenagers and young adults, the question “How do I know if my molars are growing?” usually refers to the eruption of their third molars, the wisdom teeth, as the first and second permanent molars would have already erupted years earlier. While the process isn’t as overtly dramatic as baby teething, there are distinct signs and sensations that indicate these back teeth are on the move or trying to emerge. One of the most common indicators is a feeling of **pressure or a dull ache** in the very back of the jaw, behind the second molars. This sensation can come and go. You might also notice **tenderness, redness, or swelling** of the gum tissue in that area. Sometimes, the gum might feel slightly raised or firmer than usual. As the tooth gets closer to the surface, you might be able to see a **small white bump** or a visible portion of the tooth crown starting to poke through the gum line. Pain is a significant sign, ranging from mild discomfort to more intense throbbing, especially if the tooth is impacted or pressing on a nerve. This pain can sometimes radiate towards the ear or temple. Difficulty opening your mouth wide or experiencing **stiffness or soreness in the jaw joint** can also be a sign, particularly if the erupting tooth is causing inflammation or affecting the surrounding muscles. If the wisdom tooth is only partially erupted, the flap of gum tissue covering part of the tooth can trap food particles and bacteria, leading to localized **infection (pericoronitis)**. Symptoms of infection include severe pain, significant swelling, pus, bad taste, and sometimes fever or difficulty swallowing. If you experience any of these symptoms, especially pain, swelling, or limited jaw movement, it’s crucial to schedule a dental appointment. A dentist can examine the area, take X-rays to assess the position and development of the wisdom teeth, and determine if they are erupting normally or if intervention is needed. Don’t ignore persistent symptoms; they are your body’s way of signaling that something is happening with these late-stage molars.

Understanding Molar Pain: Causes and Relief – Navigating the Discomfort and Distress That Can Arise from Issues Affecting These Vital Grinding Teeth, From Cavities and Infections to Eruption Woes and Grinding Habits, Providing Insight into Why Molars Are Susceptible and What Steps to Take for Alleviation and Treatment.

Molar pain is an incredibly common issue, often sending people to the dentist seeking urgent relief. Given their demanding role in chewing, their complex anatomy, and their position far back in the mouth which can make them harder to clean effectively, molars are particularly vulnerable to a range of problems that can cause significant discomfort. Unlike a sharp, localized pain you might feel from a chip on a front tooth, molar pain often presents as a deeper, throbbing ache, sometimes difficult to pinpoint precisely, radiating into the jaw, ear, or head. Understanding the potential sources of this pain is the first crucial step in finding effective relief. Is it a sharp twinge when you bite down? A dull, constant throb? Sensitivity to hot or cold? The nature of the pain can often provide clues to the underlying cause, which can range from the relatively common, like tooth decay, to the more complex, such as nerve issues or jaw problems. Ignoring molar pain is never advisable; it’s your body’s signal that something is wrong and requires professional attention. While temporary relief measures can help manage symptoms, a proper diagnosis from a dentist is essential to address the root cause and prevent further damage or complications. This section will explore the most frequent culprits behind molar discomfort and outline effective strategies for managing the pain, from immediate at-home measures to necessary professional treatments, empowering you to take informed action when these crucial back teeth start protesting. Recognizing the symptoms, understanding the possible causes, and knowing when and how to seek help are paramount for resolving molar pain and preserving the health and function of these indispensable teeth for the long haul.

Why are my molar teeth hurting? Exploring Common Causes – Detailing the Most Frequent Culprits Behind Molar Pain, From the Ubiquitous Cavity to More Complex Issues Like Gum Disease, Abscesses, and the Persistent Problem of Teeth Grinding, Offering Clarity on Potential Sources of Discomfort.

Molar pain can stem from a multitude of sources, each requiring a specific diagnostic approach and treatment plan. Pinpointing the exact reason your molars are hurting is crucial for effective relief and long-term dental health. One of the most prevalent causes is tooth decay (cavities). Because of their pitted and grooved chewing surfaces and their location at the back of the mouth, which makes them harder to access with a toothbrush, molars are particularly susceptible to trapping food particles and bacteria. If plaque is not thoroughly removed, acids erode the enamel, creating cavities that, if left untreated, can penetrate deeper into the tooth, reaching the sensitive inner layer (dentin) and eventually the pulp (containing nerves and blood vessels), causing significant pain, especially when exposed to hot, cold, or sweet substances, or when biting down. Gum disease (periodontal disease) is another major contributor. Inflammation and infection of the gums surrounding the molar can cause pain, swelling, and even lead to tooth looseness if the supporting bone is affected. Teeth grinding (bruxism), often stress-related and occurring unconsciously during sleep, puts immense pressure on the molars. This constant force can lead to tooth sensitivity, wear down the enamel, cause cracks, and result in aching jaw muscles and referred molar pain. A **cracked or fractured tooth**, sometimes resulting from biting something hard or from bruxism, can cause sharp, intense pain when chewing, as pressure on the crack irritates the underlying pulp. An **abscess**, a pocket of pus caused by a bacterial infection, can form at the tip of the root or in the surrounding gum tissue, often as a result of deep decay or a crack. Abscesses are notoriously painful, causing severe throbbing pain, swelling, and sometimes fever. **Impaction**, particularly of wisdom teeth, causes pain as the tooth attempts to erupt into insufficient space, pressing against nerves or adjacent teeth. Other causes can include issues with previous dental work (fillings, crowns), sinus infections (upper molar pain can be referred from the sinuses), or even temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders affecting the jaw muscles and joints connected to the molar area. Identifying the specific cause, often through a dental exam and X-rays, is the essential first step towards alleviating the pain and preserving the tooth.

Are molar teeth more painful? Discussing Whether the Characteristics of Molars Make Them Inherently More Prone to Painful Issues or Contribute to a Greater Sensation of Discomfort When Problems Arise Compared to Other Teeth in the Mouth.

The question of whether molar teeth are inherently more painful than other teeth is complex, but there’s a strong argument to be made that issues affecting molars often lead to a higher level of discomfort or pain that feels more intense or widespread. It’s not necessarily that the pain receptors in molars are different, but rather that the **nature and location of the problems** they commonly face, combined with their anatomy, contribute to more significant painful experiences. Firstly, as discussed, molars are highly susceptible to **deep cavities and infections** due to their complex chewing surfaces and cleaning difficulty. Decay or infection reaching the pulp (nerve tissue) in any tooth is painful, but molars have multiple roots and complex canal systems, meaning infections can be more involved and potentially spread, leading to widespread inflammation and severe, throbbing pain, especially in abscess formation. Secondly, the **pressure from chewing** is concentrated on the molars. Problems like cracks, fractures, or even sensitive dentin exposure on these load-bearing teeth can cause sharp, intense pain whenever you bite down, a constant reminder of the issue with every meal. **Impaction**, a common problem with wisdom teeth, involves pressure against bone, nerves, and adjacent teeth, creating pain that can be significant and radiate throughout the jaw and head. Furthermore, molars are situated at the back of the mouth, closer to major nerves and the temporomandibular joint. Pain originating from a molar can therefore be **referred** to other areas, like the ear, temple, or jaw, making it feel more diffuse and harder to ignore than a sharp pain in a front tooth. Finally, the larger size and multiple roots mean that issues like root canal treatment on molars are often more complex procedures than on single-rooted teeth, and post-operative recovery from procedures like molar extractions (especially wisdom teeth) can involve significant swelling and discomfort. While pain perception is subjective, the common issues affecting molars – deep decay, infection, cracks under chewing pressure, impaction, and their proximity to major nerve pathways – frequently result in painful experiences that are often perceived as more severe or debilitating compared to problems with anterior teeth.

What to Know and Do About Molar Tooth Pain – Providing Immediate Guidance on Managing Molar Pain Symptoms at Home While Emphasizing the Non-Negotiable Importance of Consulting a Dentist for Proper Diagnosis and Definitive Treatment to Address the Underlying Cause.

Experiencing molar tooth pain can be incredibly disruptive and concerning. While your ultimate goal must be to see a dental professional for a proper diagnosis and treatment, there are steps you can take immediately to help manage the discomfort while you await your appointment. First and foremost, **do not ignore molar pain**. It is a symptom indicating a problem that will likely worsen without professional intervention. What you *can* do at home involves temporary relief measures. Over-the-counter (OTC) pain relievers like ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin) or acetaminophen (Tylenol) can help reduce pain and inflammation. Be sure to follow the dosage instructions carefully and consider any existing health conditions or medications you are taking. A **warm salt water rinse** (dissolving half a teaspoon of salt in a glass of warm water) is an excellent home remedy. Swishing this solution gently in your mouth, especially around the painful area, several times a day can help reduce inflammation, clean the area, and potentially draw out infection. A **cold compress** applied to the outside of your cheek near the painful tooth can help reduce swelling and numb the area, providing temporary relief. Apply for 15-20 minutes at a time, several times a day. **Avoiding trigger foods and temperatures** is also wise. If your tooth is sensitive to hot or cold, stick to lukewarm foods and drinks. If biting down causes pain, avoid chewing on the affected side. Clove oil (applied sparingly to the painful tooth or gum with a cotton swab) is a traditional remedy that contains eugenol, a natural anesthetic, but use with caution and understand it’s a temporary fix. While these home remedies can offer temporary respite, they do not address the underlying cause of the pain, which could be decay, infection, a crack, or something else. **The most critical step is to schedule an appointment with a dentist as soon as possible.** They can perform a thorough examination, take X-rays, determine the source of the pain, and recommend the appropriate treatment, which might include fillings, root canals, antibiotics for infection, or extraction. Delaying professional care can lead to the problem worsening, potentially resulting in more complex and costly treatments down the line. Temporary relief is good, but definitive professional treatment is essential.

Tips to manage molar pain symptoms – Offering Practical, Actionable Advice for Coping With the Discomfort of Molar Pain While Waiting for Professional Dental Care, Focusing on Non-Prescription Methods and Lifestyle Adjustments for Temporary Alleviation.

Managing molar pain can be challenging, but a few practical strategies can help you cope until you can see a dentist. Beyond the initial steps mentioned earlier, implementing a combination of approaches can offer more comprehensive temporary relief. Firstly, **maintain impeccable oral hygiene**, even if it’s uncomfortable. Gentle brushing around the affected area is important to remove food particles and plaque that could be exacerbating the issue. Continue with warm salt water rinses regularly – several times a day, especially after eating. If brushing is too painful, try using a very soft toothbrush or simply rinsing thoroughly after meals. Consider using a **topical over-the-counter pain relief gel or cream** designed for oral use. These often contain benzocaine, a local anesthetic that can temporarily numb the gum tissue around the painful tooth. Follow the product instructions carefully. Be mindful of your **diet**. Avoid hard, crunchy, or sticky foods that could put pressure on the tooth or get stuck in cavities or gum pockets. Extremely hot or cold foods and sugary or acidic drinks can also worsen sensitivity; opt for lukewarm, soft foods instead. If you suspect teeth grinding (bruxism) is contributing to your pain, try stress-reduction techniques. While a custom nightguard is the long-term solution, being mindful of clenching your jaw during the day can help. Some find applying a warm, moist heat pack to the jaw before bed can relax the muscles. **Elevating your head** slightly when sleeping can sometimes help reduce throbbing pain, as it can decrease blood flow and pressure in the area. If the pain is making it difficult to sleep, try taking an OTC pain reliever about 30-60 minutes before bed. Remember, these are management techniques for the *symptoms* of pain. They are not cures and should not replace professional dental care. Use these tips to make yourself more comfortable, but prioritize getting a dental appointment to identify and treat the source of your molar pain effectively and permanently.

What relieves molar pain? Summarizing the Spectrum of Relief Methods, From Accessible Home Remedies and Over-the-Counter Options to the Essential Professional Dental Treatments Necessary to Address the Root Cause of Discomfort in Molar Teeth.

Effective relief from molar pain often involves a multi-pronged approach, combining immediate symptom management with definitive treatment of the underlying cause. Relying solely on temporary fixes will likely lead to recurring or worsening pain and potentially more severe dental issues down the line. **Immediate, temporary relief** can often be found using:

1. **Over-the-Counter Pain Relievers:** Medications like ibuprofen (an anti-inflammatory) or acetaminophen (a pain reducer) are standard first-line options.

2. **Warm Salt Water Rinses:** Helps reduce inflammation and cleanse the area.

3. **Cold Compress:** Applied externally to the cheek to numb pain and reduce swelling.

4. **Topical Anesthetics:** Gels or creams applied directly to the gum tissue for temporary numbing.

5. **Avoiding Triggers:** Steering clear of hot, cold, sweet, hard, or sticky foods that aggravate the pain.

These methods provide a temporary reprieve, buying you time until you can receive professional care. However, for **definitive and lasting relief**, professional dental treatment is indispensable. The specific treatment will depend entirely on the dentist’s diagnosis of the pain’s cause:

1. **Fillings:** If the pain is due to a cavity that hasn’t reached the pulp, removing the decay and filling the tooth will resolve the sensitivity and prevent further progression.

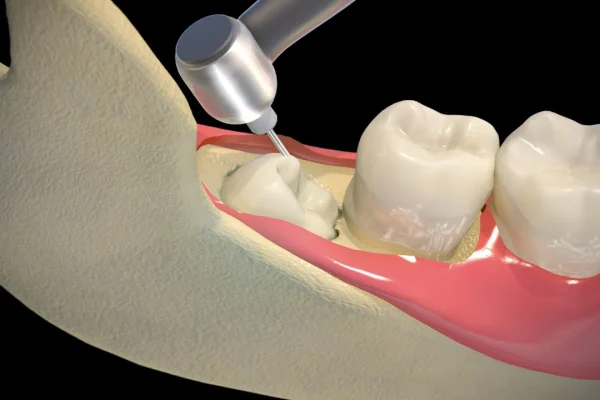

2. Root Canal Treatment (Endodontics): If decay or a crack has infected the pulp, a root canal is performed to remove the damaged nerve tissue, disinfect the root canals, and seal them, saving the tooth and eliminating the source of internal pain. Molars are complex, making these procedures intricate.

3. **Antibiotics:** If an infection (like an abscess) is present, a dentist may prescribe antibiotics to clear the infection, often in conjunction with a root canal or drainage.

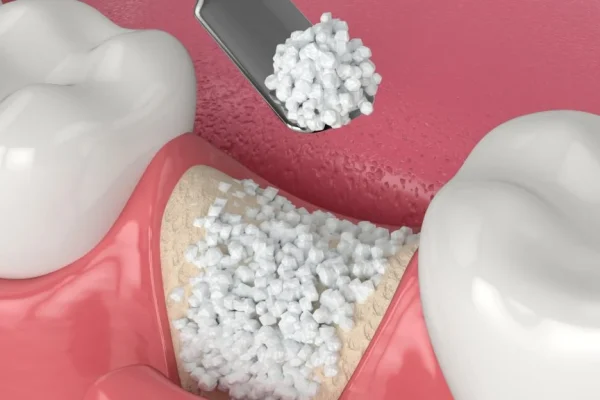

4. **Extraction:** In cases of severe decay, irreparable damage, untreatable infection, or problematic impaction (especially wisdom teeth), removing the tooth might be necessary to eliminate the pain and prevent harm to surrounding structures.

5. **Gum Disease Treatment:** Scaling and root planing or other periodontal procedures are needed if gum disease is the cause of the pain.

6. **Nightguard:** For pain caused by bruxism, a custom-fitted nightguard protects the teeth from grinding forces.

In summary, while home remedies and OTC medications can offer comfort in the short term, the only way to truly relieve molar pain and prevent its recurrence is through a proper dental examination and appropriate professional treatment tailored to the specific underlying issue. Don’t self-diagnose for too long; seek help to get to the root of the problem.

General Molar Extraction and Removal Explained – Addressing the Process of Removing a Molar Tooth When Necessary, Exploring the Reasons Why Extraction Might Be the Best Course of Action, and What to Expect During and After the Procedure.

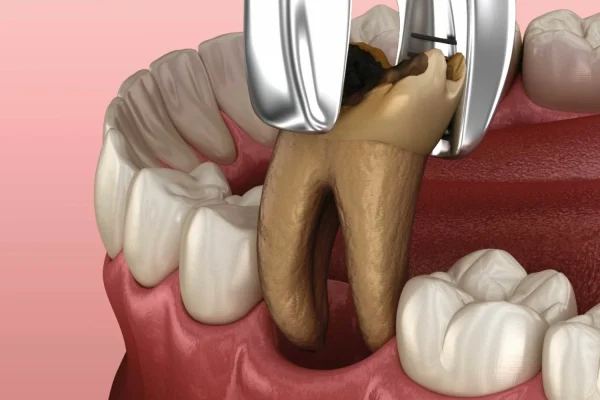

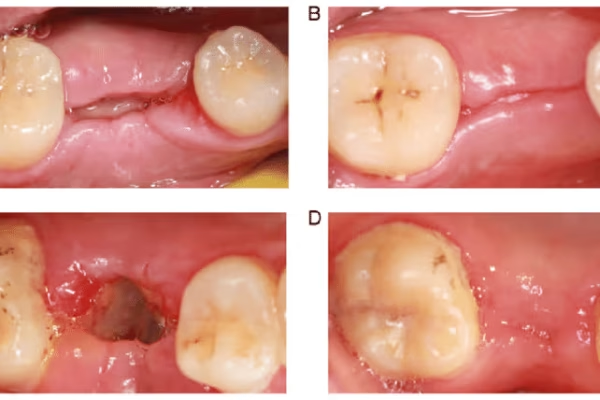

Sometimes, despite best efforts at prevention and treatment, a molar tooth reaches a point where it cannot be saved or its presence poses a risk to overall oral health. In such cases, molar extraction becomes a necessary procedure. Extraction is essentially the removal of a tooth from its socket in the jawbone. While it’s often considered a last resort, a skilled dentist or oral surgeon can perform extractions safely and effectively when indicated. The decision to extract a molar is never taken lightly and is made after a thorough examination, including X-rays, and discussion of all possible treatment alternatives. The primary goal of dentistry is always to preserve natural teeth whenever possible, but there are situations where removal is the most beneficial option for a patient’s health and well-being. Understanding the reasons for extraction and what the process entails can help alleviate anxiety for those facing the prospect of losing a molar. The procedure varies depending on the complexity of the tooth’s roots and whether it has fully erupted, but modern techniques and anesthesia ensure that the process itself is typically not painful. Recovery, however, requires care and adherence to post-operative instructions to ensure proper healing and prevent complications. This section outlines the common scenarios that lead to molar removal and provides a realistic overview of the extraction experience, empowering patients with knowledge about a procedure that, while often regrettable, is sometimes essential for maintaining a healthy mouth and preventing further pain and problems down the line. Knowing when removal is indicated and who performs it helps clarify the process.

Should I remove a molar tooth? When is it Necessary? Delving into the Specific Situations Where Extracting a Molar Becomes the Recommended Course of Action, Prioritizing Patient Health and the Prevention of More Significant Future Problems Over Tooth Preservation.

The question of whether to remove a molar tooth is a significant one, and the answer is always determined by a dental professional based on the specific condition of the tooth and its impact on overall oral health. While dentists strive to save natural teeth whenever possible through treatments like fillings, crowns, or root canals, there are unavoidable circumstances where extraction is deemed necessary. One of the most common reasons is **severe tooth decay** that has progressed to the point where the tooth structure is too compromised to be restored with a filling or crown, and a root canal is either not feasible, unsuccessful, or the tooth has fractured below the gum line. An **untreatable infection or abscess** that cannot be resolved through root canal therapy or other means is another clear indication for extraction, as the infection can spread and affect surrounding tissues and bone. Advanced gum disease (periodontal disease) can severely damage the supporting bone and ligaments around a molar, causing it to become significantly loose and potentially painful, making extraction the best option to prevent the spread of infection and preserve adjacent teeth. A tooth that is **irreparably damaged** due to trauma or a fracture that extends deep into the root is also typically a candidate for removal. Finally, **impaction or significant misalignment**, particularly common with wisdom teeth but occasionally affecting other molars, can necessitate extraction if the tooth is causing pain, infection, damage to neighbouring teeth, or crowding that affects orthodontic treatment plans. Orthodontic treatment sometimes requires the removal of healthy molars (often premolars, but occasionally first molars in specific treatment plans) to create space for aligning other teeth. The decision to extract is always a collaborative one between the patient and dentist, weighing the benefits (eliminating pain, preventing spread of infection, resolving orthodontic issues) against the drawbacks (loss of a tooth, potential need for replacement). If a molar is causing chronic problems, posing a risk to other teeth, or is beyond saving, removal is often the necessary and ultimately beneficial step for long-term oral health.

Can a dentist remove a molar? Clarifying Which Dental Professionals Are Qualified to Perform Molar Extractions, Depending on the Complexity of the Procedure, and When Referral to a Specialist Might Be Necessary.

Yes, a **general dentist is certainly capable of performing many molar extractions**. General dentists are trained in a wide range of dental procedures, including routine tooth extractions. If a molar is fully erupted, relatively healthy structurally (apart from the reason for extraction, like severe decay), and has a straightforward root anatomy, a general dentist can typically perform the extraction successfully in their office under local anesthesia. This is often referred to as a “simple extraction.” However, molars, particularly those with multiple, curved, or divergent roots, can sometimes present complexities that require specialized skills and equipment. Therefore, in certain situations, a general dentist may refer a patient to an **oral and maxillofacial surgeon**, a specialist with advanced training in surgical procedures involving the mouth, jaw, and face. Referrals are common for **surgical extractions**, which are required when a tooth is impacted (especially wisdom teeth), hasn’t fully erupted, is broken off at the gum line, or has complex roots or is closely positioned near important nerves or the sinus cavity. Oral surgeons have the expertise and facilities to handle more complicated cases, often utilizing techniques like sectioning the tooth into pieces before removal or accessing teeth that are still partially or fully embedded in bone or gum tissue. They may also offer different types of anesthesia, such as sedation or general anesthesia, which might be preferred for more complex procedures or anxious patients. So, while your family dentist can handle many molar extractions, they will assess the difficulty of the case during your examination. If they determine the extraction requires specialized surgical skill or is outside the scope of procedures they routinely perform, they will confidently refer you to an oral surgeon, ensuring you receive the safest and most appropriate care for your specific situation.

Does removing a molar hurt? Addressing the Common Concern About Pain During and After Molar Extraction, Explaining the Role of Anesthesia in the Procedure Itself and the Expected Discomfort During the Healing and Recovery Period.

The prospect of having a tooth removed, particularly a large molar, understandably causes concern about pain. However, it’s important to differentiate between the sensation *during* the procedure and the discomfort experienced *after* the procedure during the healing phase. **During the extraction itself, you should not feel pain.** Modern dental practices utilize highly effective local anesthesia, which is administered via injection around the tooth and surrounding gum tissue. This numbs the area completely, blocking pain signals from reaching the brain. You will feel pressure and movement as the dentist or surgeon works to loosen and remove the tooth from its socket, and you might hear some sounds, but the sensation of sharp pain should be absent. If at any point you do feel pain during the procedure, it is crucial to immediately signal your dentist or surgeon, as they can administer more anesthetic to ensure you are comfortable. The discomfort comes **after the extraction**, as the local anesthetic wears off and the body begins the healing process. It’s entirely normal to experience pain, swelling, bruising, and tenderness in the extraction site and surrounding jaw area for several days following the procedure. The intensity of this post-operative pain varies depending on the complexity of the extraction (e.g., a surgical extraction of an impacted wisdom tooth is typically more painful than a simple extraction of a fully erupted molar) and individual pain tolerance. Dentists and oral surgeons will provide detailed post-operative instructions and usually prescribe or recommend pain medication to manage this discomfort effectively. This might include prescription pain relievers for the first few days, followed by over-the-counter options as the pain subsides. Following instructions regarding diet (soft foods), cleaning (gentle rinsing), and activity level is crucial for minimizing pain and preventing complications like dry socket. So, while the procedure itself should be pain-free thanks to anesthesia, anticipate and prepare for several days of manageable discomfort as your mouth heals, knowing that it’s a normal part of the recovery process after a molar has been removed.

Wisdom Teeth (Third Molars): Specifics and Removal – Focusing Exclusively on the Third Molars, Unpacking Their Unique Developmental Challenges, Common Issues Leading to Their Extraction, and What to Expect From the Often-Necessary Surgical Removal Procedure.

Ah, wisdom teeth. They occupy a unique and often troublesome place in the human dental narrative. As the last teeth to emerge, usually in late adolescence or early adulthood, they frequently encounter a world where there simply isn’t enough room for them. This lack of space, a common evolutionary mismatch in modern humans, leads to a high incidence of problems, making wisdom tooth extraction one of the most common surgical procedures performed globally. Situated at the very back of the mouth, behind the second molars, these third molars were perhaps more functional for our ancestors with larger jaws and coarser diets requiring maximum grinding capacity. Today, however, they often become impacted – trapped within the jawbone or only partially erupting – causing pain, infection, and damage to adjacent teeth. Even when they do fully erupt, their location makes them exceedingly difficult to clean effectively, leaving them vulnerable to decay and gum disease. Consequently, the removal of wisdom teeth is a frequent recommendation to prevent or alleviate these issues. This section delves into the specific challenges posed by these late-arriving molars, explores the primary reasons why extraction is so often necessary, and outlines the process of wisdom tooth removal, addressing common concerns about pain and recovery. Understanding the nuances of these particular molars is crucial for anyone approaching the typical age of their eruption or experiencing symptoms related to their presence. They might be the “wisdom” teeth, but managing them often requires proactive dental intervention to prevent future problems, highlighting the sometimes-awkward reality of our evolutionary dental inheritance.

Wisdom teeth (third molars) – Why They Cause Problems – Exploring the Primary Reasons These Late-Arriving Molars Are So Frequently Troublesome, Focusing on Lack of Space, Impaction, and Difficulties in Maintaining Proper Oral Hygiene Due to Their Location.

The notoriety of wisdom teeth (third molars) as problematic teeth is well-earned, largely stemming from their timing of eruption and their position at the very back of the mouth. The fundamental issue for many individuals is a simple lack of **sufficient space** in the jaw to accommodate these final four molars. By the time they attempt to erupt, typically between the ages of 17 and 25, the jawbone has often completed or significantly completed its growth. If the dental arch isn’t long enough, the wisdom teeth don’t have a clear path to emerge fully and properly align with the other teeth. This leads to the most common problem: **impaction**. An impacted wisdom tooth is one that is prevented from fully erupting into the mouth. This can happen for various reasons: the tooth might be growing at an angle towards the adjacent second molar, angled backwards, growing straight up but trapped under the gum and bone, or only partially emerging. Impacted teeth can cause significant pain, swelling, and pressure. They can also damage the roots of the neighbouring second molar by pressing against them. Furthermore, partially erupted wisdom teeth are particularly problematic. The flap of gum tissue covering part of the tooth (an operculum) can easily trap food particles, plaque, and bacteria, creating a perfect breeding ground for infection, a painful condition known as **pericoronitis**. This infection causes inflammation, swelling, pain, and sometimes difficulty opening the mouth. Even when wisdom teeth do fully erupt and are not impacted, their location at the far back of the mouth makes them incredibly **difficult to clean effectively** with regular brushing and flossing. This poor accessibility significantly increases their susceptibility to cavities and gum disease compared to other teeth. Decay can progress rapidly in wisdom teeth due to inadequate hygiene. In some cases, the presence of wisdom teeth, even if not impacted, can contribute to **crowding** or shifting of other teeth, although this is a subject of ongoing debate in the orthodontic community. Collectively, these factors – lack of space leading to impaction, high risk of infection in partially erupted teeth, and challenges with hygiene in fully erupted ones – explain why wisdom teeth are so frequently associated with pain, infection, and necessitate removal.

Why remove wisdom teeth? Listing the Primary Medical and Dental Reasons That Often Lead to the Recommendation for Wisdom Tooth Extraction, Focusing on Prevention of Future Problems and Resolution of Existing Issues Caused by Their Presence.

The decision to remove wisdom teeth is typically based on preventing or resolving specific problems that their presence causes or is likely to cause. It’s not a universal requirement for everyone to have them removed, but for a significant portion of the population, extraction is the most prudent course of action for long-term oral health. The primary reasons dentists and oral surgeons recommend wisdom tooth removal include:

1. **Impaction and Related Issues:** This is the most common reason. Impacted teeth can cause chronic pain, swelling, and pressure. They can also lead to cysts or tumours developing around them in rare cases. Removing the impacted tooth eliminates these risks and symptoms.

2. **Infection (Pericoronitis):** Partially erupted wisdom teeth are highly prone to pericoronitis, a painful infection of the gum tissue surrounding the tooth. This infection can recur and spread if the tooth is not removed.

3. **Damage to Adjacent Teeth:** An impacted wisdom tooth can press against the roots of the second molar, potentially causing root resorption (damage) or increasing the risk of decay on the second molar due to trapped food and bacteria in the difficult-to-clean area between the teeth. Removing the wisdom tooth protects the valuable second molar.

4. **Cavities and Gum Disease:** Even fully erupted wisdom teeth are often difficult to clean properly because of their location. This makes them highly susceptible to developing deep cavities or localized gum disease that cannot be effectively treated or managed, posing a risk to overall oral health. Removing them prevents these chronic problems.

5. **Orthodontic Concerns:** Although controversial, in some cases, wisdom teeth are removed as part of an orthodontic treatment plan to help prevent relapse or crowding of the front teeth after braces, particularly if there is already significant crowding in the arch.

6. **Preventive Measures:** Sometimes, even if wisdom teeth aren’t currently causing symptoms, X-rays may show that they are likely to cause problems in the future (e.g., high likelihood of impaction, poor position, or cystic changes). In such cases, extraction may be recommended as a proactive measure to avoid more complicated issues or pain later in life when recovery might be slower.

Ultimately, the goal of removing wisdom teeth is to preserve the health of the rest of the mouth, alleviate existing pain or infection, and prevent foreseeable future complications that could be more difficult or painful to treat.

How painful is wisdom teeth removal? Providing a Realistic Expectation of Discomfort During the Recovery Period Following Wisdom Tooth Surgery, and How Pain Is Typically Managed to Ensure Patient Comfort During Healing.

The question of pain is often the biggest concern for individuals facing wisdom tooth removal. It’s important to be realistic: **you will experience discomfort and pain after wisdom tooth surgery**, as it is a surgical procedure involving incisions and working with bone tissue, especially if the teeth are impacted. However, the procedure itself, performed under local anesthesia, sedation, or general anesthesia, is designed to be pain-free. The pain begins once the effects of the anesthetic wear off, typically several hours after the surgery. The level of pain and duration of discomfort vary greatly depending on the complexity of the extractions (e.g., removing four deeply impacted teeth is generally more uncomfortable than removing one fully erupted tooth) and individual pain tolerance. Most patients describe the post-operative pain as moderate to severe in the first 24-72 hours, gradually improving each day thereafter. This pain is accompanied by swelling (often peaking 48-72 hours after surgery), bruising, and stiffness in the jaw muscles, which can make opening the mouth and eating difficult. To manage this expected discomfort, oral surgeons and dentists provide a pain management plan. This typically involves a combination of medications. Prescription pain relievers (often opioids for the first few days, followed by non-opioid options) are commonly prescribed for more complex extractions. Over-the-counter pain relievers like ibuprofen (which also helps with inflammation) are usually recommended alongside or after prescription medication as the pain subsides. Following post-operative instructions meticulously is key to managing pain and promoting healing. This includes taking medications as prescribed, using ice packs on the cheeks to reduce swelling, eating only soft foods, staying hydrated, and avoiding activities that could dislodge the blood clot (like smoking, vigorous rinsing, or using straws), which can lead to a painful condition called dry socket. While you won’t be pain-free immediately, the pain is manageable with medication and diminishes significantly over the first week. Full recovery, where most swelling and discomfort resolve, typically takes about 1 to 2 weeks, though complete tissue healing takes longer. Communicate any severe or worsening pain to your surgeon; while discomfort is normal, excessive or increasing pain could indicate a complication.

What are the side effects of removing wisdom teeth? Outlining the Common and Less Common Post-Operative Effects Following Wisdom Tooth Extraction, Helping Patients Understand the Normal Healing Process and Recognize Potential Complications That Require Attention.

Following wisdom tooth removal, experiencing certain side effects is a normal part of the healing process. Understanding what to expect can help you manage your recovery effectively and differentiate normal post-operative symptoms from potential complications. The most common side effects include:

1. **Pain:** As discussed, pain is expected and managed with medication, gradually decreasing over several days.

2. **Swelling:** Swelling of the cheeks and jaw is very common and can make your face look visibly puffy. It usually peaks 2-3 days after surgery and gradually subsides over the following week. Using ice packs intermittently for the first 24-48 hours is crucial for minimizing swelling.

3. **Bruising:** Bruising on the face and neck along the jawline is also common, particularly with more difficult extractions. The colour may change over several days, similar to any bruise, before fading completely within a week or two.

4. **Bleeding:** Some oozing or light bleeding from the extraction sites is normal for the first 24 hours. Gauze pads are provided to apply pressure to the sockets. Persistent or heavy bleeding should be reported to your surgeon.

5. **Limited Mouth Opening (Trismus):** Stiffness and soreness in the jaw muscles can make it difficult to open your mouth wide for several days. This usually improves gradually. Gentle jaw exercises might be recommended as you heal.

6. **Numbness or Tingling:** Temporary numbness or tingling in the lip, tongue, or chin can occur if the tooth roots were close to nerves. This is usually temporary and resolves within days or weeks, but in rare cases, it can be permanent (though this is very uncommon).

Less common but potentially serious complications include:

7. **Dry Socket (Alveolar Osteitis):** This is a painful condition occurring when the blood clot in the extraction socket dislodges or dissolves prematurely, exposing the underlying bone and nerves. It typically develops 2-5 days after surgery and causes intense pain radiating towards the ear. It requires immediate dental attention to be treated.

8. **Infection:** Although antibiotics are sometimes prescribed proactively, infection can occur in the socket, causing increased pain, swelling, redness, pus, and fever.

9. **Damage to Adjacent Teeth or Restorations:** Rarely, removal can affect nearby teeth or dental work.

10. **Sinus Communication (for upper teeth):** If the roots of an upper wisdom tooth were close to the sinus, a small opening might be created, usually healing on its own, but requiring care to avoid blowing your nose forcefully.

Reporting any severe, worsening, or unusual symptoms to your oral surgeon is essential to ensure timely management and a smooth recovery.

Living Without or Losing Molars – Exploring the Scenarios Where Individuals No Longer Have Their Molars, Whether Through Natural Shedding of Primary Teeth or the Unfortunate Loss of Permanent Ones, and Discussing the Implications and Replacement Options.

The presence of a full complement of molars is fundamental to efficient chewing and maintaining the structural integrity of the bite. However, there are circumstances where individuals may find themselves living without some or all of these crucial back teeth. For children, the loss of molars is a normal and expected part of development, as their primary molars are shed to make way for permanent teeth (specifically, premolars). For adults, however, the loss of a permanent molar is usually the result of dental disease, trauma, or necessary extraction, and it signifies a significant change in their oral landscape with potential functional consequences. Living without a permanent molar can impact chewing ability, affect the alignment of remaining teeth, and even lead to bone loss in the jaw. This section addresses these different scenarios of molar loss – the natural shedding in childhood versus the often-unfortunate loss in adulthood – clarifies which molars are naturally lost, explores the potential implications of living with missing permanent molars, discusses the feasibility and challenges of eating without them, and briefly touches upon why replacing a lost permanent molar is often highly recommended to maintain long-term oral health and function. Understanding the distinctions between primary and permanent molar loss and recognizing the potential impacts of missing permanent teeth is key to making informed decisions about dental care and exploring appropriate solutions to restore the bite and preserve oral health for the future. The journey through the lifespan of molars includes both their arrival and, sometimes, their departure.

Do molars fall out? Clarifying Which Set of Molars Is Naturally Shed During Development and Which Set Is Intended to Last a Lifetime, Addressing a Common Question About the Lifespan of These Different Types of Teeth.

The simple answer is **yes, some molars do fall out, but only the primary ones.** This is a critical distinction to understand when thinking about dental development across a lifetime. The **primary molars**, also known as “baby molars” or deciduous molars, are temporary teeth. A child has two primary molars in each quadrant (eight in total), and these begin to erupt in infancy. They serve their purpose of chewing food during early childhood. As the child grows and their jaw develops, the roots of these primary molars gradually resorb (dissolve), and the permanent teeth that are developing beneath them begin to push upwards. This natural process causes the primary molars to become loose and eventually fall out. This shedding of primary molars typically occurs between the ages of 10 and 12, making way for the eruption of the **permanent premolars**, not permanent molars, which replace them in that specific position in the dental arch. **Permanent molars**, on the other hand, are **not supposed to fall out**. The three sets of permanent molars (first, second, and third/wisdom teeth) erupt behind where the primary teeth were located, adding to the total number of teeth. Once they have fully erupted and their roots are formed, they are anchored securely in the jawbone and are intended to last a lifetime. If a permanent molar falls out, it is a sign of a significant underlying problem, such as severe gum disease that has destroyed the supporting bone, extensive untreated decay that has weakened the tooth structure, trauma, or unsuccessful dental treatment that led to tooth loss. So, while primary molars falling out is a normal developmental milestone, a permanent molar falling out is a serious issue that requires immediate dental attention to determine the cause and discuss replacement options.

What age do molars come out? Specifying the Typical Age Range for the Natural Shedding of Primary Molars, Marking a Key Transition in a Child’s Dental Development as They Prepare for the Permanent Dentition.

The phrase “what age do molars come out” refers specifically to the **natural shedding of primary molars**. This process is a normal and expected part of a child’s transition from primary to permanent dentition. Primary molars, which function as the main grinding teeth in young children, are not intended to be permanent. They are typically shed to make way for the eruption of the permanent teeth that will occupy those spaces in the dental arch. This shedding process for primary molars usually occurs between the ages of **10 and 12 years old**. It’s often one of the later tooth-loss milestones in childhood, happening after most of the primary front teeth and canines have already been lost and replaced by their permanent successors. The order in which the first and second primary molars are lost can vary slightly from child to child. As the permanent premolars develop beneath the primary molars, their growth and pressure cause the roots of the primary teeth to dissolve. This resorption weakens the primary molar’s anchor in the bone, causing it to become loose. Eventually, the primary molar becomes sufficiently loose that it falls out, often aided by chewing or simply dislodged during daily activities. The space is then available for the permanent premolar (which is different from a permanent molar) to erupt into position, typically within a few months. So, for primary molars, “coming out” is a scheduled event in pre-adolescence, part of the body’s natural process of preparing the mouth for the full set of larger, permanent teeth required for adulthood. It’s important for parents to understand that while losing primary molars is normal, it’s the permanent premolars, not permanent molars, that take their place.

Which molars do you lose? Clarifying Which Specific Molars Are Naturally Shed During Childhood and Emphasizing That Permanent Molars Are Not Meant to Be Lost, Highlighting the Difference Between the Primary and Permanent Sets in Terms of Their Lifespan and Replacement Pattern.