Table of Contents

ToggleKey Takeaways

- Cavities are permanent holes in teeth caused by tooth decay.

- Tooth decay is a disease process driven by bacteria, sugar, and acid.

- Early cavities often have no symptoms; pain usually indicates advanced decay.

- Cavities cannot heal on their own and require professional dental treatment.

- Prevention through good hygiene, diet control, fluoride, and regular dental visits is key.

- Leaving cavities untreated leads to worsening pain, infection, tooth loss, and potentially serious health complications.

Understanding Cavity: What Are They and Why Do They Occur?

Stepping beyond the casual “it’s a hole,” let’s get granular. A cavity, clinically known as dental caries, is essentially permanently damaged areas in the hard surface of your teeth that develop into tiny openings or holes. This damage is progressive; it doesn’t appear overnight. It starts as tooth decay, a biological process driven by a complex interplay of factors within your mouth. Imagine your tooth enamel, the outermost layer, as a formidable shield, incredibly strong and resistant. However, certain conditions can weaken this shield. The primary culprits are specific types of bacteria that live in your mouth, constantly forming a sticky film called plaque. These bacteria have a particular fondness for sugars and other fermentable carbohydrates left behind after you eat or drink. When they consume these substances, they produce acids as a byproduct. It’s these acids, not the sugar itself directly, that are the foot soldiers of decay. They attack the minerals in your enamel in a process called demineralization. Initially, this is a microscopic assault, invisible to the naked eye. Your saliva can help counteract this by neutralizing acids and providing minerals for remineralization, a natural repair process. But if the acid attacks are too frequent – say, you’re constantly sipping on sugary drinks or snacking throughout the day without cleaning your teeth – the balance tips. Demineralization outpaces remineralization, the enamel weakens, and eventually, the surface structure breaks down. That’s when a cavity, a literal hole or lesion, begins to form. While cavities are exceedingly common across all age groups, especially among children and older adults, their prevalence doesn’t equate to normalcy in a health context. They are the most common chronic disease globally, according to the World Health Organization, a testament to our modern diets and, often, inadequate oral hygiene practices. Therefore, while you might know many people with cavities, viewing them as an inevitable or ‘normal’ part of having teeth isn’t accurate; they are preventable. Understanding this fundamental process – the bacterial-sugar-acid connection leading to enamel erosion and eventual cavity formation – is paramount. It moves cavities from the realm of bad luck into the territory of a treatable and largely preventable condition, offering hope and empowering individuals to take charge of their oral health destiny. This knowledge forms the bedrock of effective prevention and timely intervention.

What is a Cavity and Tooth Decay?

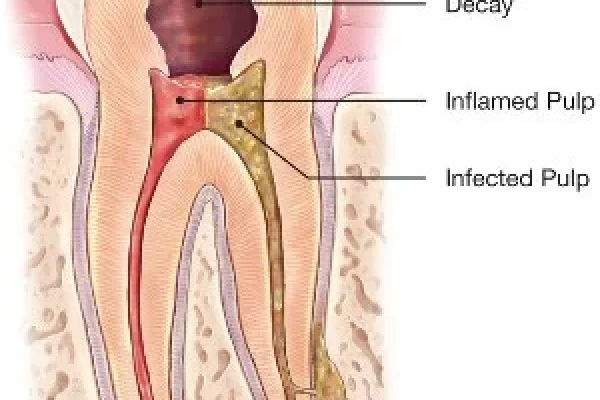

To truly grasp what a cavity is, we need to start with its origin story: tooth decay. Think of tooth decay, or dental caries, as the chronic disease process itself – the relentless assault on your tooth structure. A cavity is the result of this process, the physical manifestation of the damage. It’s like the difference between the disease (cancer) and the tumor (the physical lump). Tooth decay begins when acids produced by bacteria in plaque dissolve the mineral structure of the enamel. This demineralization process weakens the enamel, initially appearing as white spots on the tooth surface (more on stages later!). If this process continues unchecked, the enamel will eventually break down, forming a hole – the cavity. This hole can then expand, progressing deeper through the tooth layers, from the enamel to the softer dentin beneath, and eventually reaching the pulp, which contains the nerves and blood vessels. This journey through the tooth’s architecture is the progression of decay. The terms “cavity” and “tooth decay” are often used interchangeably in everyday conversation, which is understandable because the cavity is the decayed area, but it’s helpful to remember that decay is the ongoing disease, and the cavity is the hole it creates. This distinction highlights that managing dental caries isn’t just about filling the hole, but also about addressing the underlying disease process to prevent new ones and stop the existing one from worsening. Resources like the Mayo Clinic, MedlinePlus, the American Dental Association (ADA), the NHS in the UK, and even Wikipedia provide extensive information on this topic, consistently defining dental caries as the disease leading to cavities and emphasizing the bacterial and acid-driven nature of the problem. They explain how the breakdown of enamel and dentin leads to the formation of these structural defects, which are the hallmark of advanced decay, underscoring the importance of understanding the biology behind this common affliction.

What Causes Cavities and What Puts You at Risk?

Okay, let’s talk turkey about the aggressors. You’ve heard the whisper – “sugar causes cavities.” But it’s not just the sugar loaf itself that’s the villain; it’s more nuanced, a true conspiracy involving microscopic life and specific consumables. The primary culprits in the cavity saga are specific strains of oral bacteria, most notably Streptococcus mutans and Lactobacillus. These aren’t just random freeloaders; they’re particularly good at sticking to your teeth and converting the sugars and other fermentable carbohydrates you eat into acids. We’re talking about sucrose (table sugar), glucose, fructose, and even the carbs found in bread, pasta, and starchy snacks. When these bacteria feast, they excrete lactic acid, which is highly corrosive to the mineral structure of your tooth enamel. This acid bath lowers the pH level in your mouth, especially within the plaque film where the bacteria are concentrated. The constant exposure of your enamel to this acidic environment leads to the gradual loss of minerals – calcium and phosphate – from the tooth surface. This is the demineralization process we touched on earlier. If these acid attacks happen frequently throughout the day, perhaps because you’re snacking often or sipping on sugary or acidic drinks over extended periods, your saliva doesn’t get a chance to neutralize the acid and help the enamel repair itself through remineralization. The result is a net loss of minerals, weakening the enamel until it eventually collapses, forming that dreaded hole we call a cavity. This acid erosion is the core mechanism of tooth decay. Beyond this fundamental process, several factors can significantly increase your risk of developing cavities. Poor oral hygiene is a big one – insufficient brushing and flossing allow plaque and bacteria to accumulate and thrive. A diet high in sugars and frequent snacking provide a constant food source for acid-producing bacteria. Dry mouth, or xerostomia, is another major risk factor because saliva plays a crucial role in washing away food particles, neutralizing acids, and remineralizing enamel; reduced saliva flow removes this natural defense mechanism. Certain medical conditions or medications can cause dry mouth. Eating disorders like bulimia can expose teeth to stomach acid, which is highly erosive. Even the location of a tooth can matter – back teeth (molars and premolars) have lots of pits and fissures that can trap food particles and plaque, making them more susceptible. Lack of fluoride exposure, either through toothpaste, fluoridated water, or dental treatments, weakens the enamel’s resistance. Worn dental restorations or poorly fitting fillings can create traps for food and bacteria. And finally, genetics can play a role in susceptibility, though lifestyle and hygiene are usually the dominant factors. Understanding these causes and risks allows for targeted prevention strategies, forming the basis of proactive oral health management to protect your smile from decay’s relentless progression.

Does Sugar Cause Cavities?

Let’s be crystal clear: while sugar doesn’t directly drill the hole, it is undeniably the primary fuel source for the bacteria that do the drilling. The relationship is intimate and destructive. When you consume sugar, particularly sucrose (the stuff in your sugar bowl, fizzy drinks, sweets, cakes, etc.), but also other fermentable carbohydrates found in many foods, the bacteria in the plaque on your teeth have a banquet. They metabolize these sugars incredibly quickly, producing acids – primarily lactic acid – as a waste product. This process happens within minutes of sugar exposure. The plaque acts like a tiny, acidic tent on your tooth surface, holding the acid in close contact with the enamel. This acid then begins to dissolve the minerals (calcium and phosphate) in the enamel. The longer the sugar sits on your teeth, and the more frequently you expose your teeth to sugar throughout the day, the more time these bacteria have to produce acid, and the longer your enamel is subjected to this demineralizing attack. Sipping on a sugary drink over an hour is far worse than drinking it quickly and then rinsing your mouth, as it prolongs the acid exposure. Snacking frequently on sugary or starchy foods without brushing or rinsing has the same effect. So, yes, sugar is a major instigator. It feeds the acid-producing bacteria, creating the acidic environment necessary for enamel demineralization and ultimately, cavity formation. Reducing your intake of sugary foods and drinks, especially between meals, and practicing good oral hygiene immediately after consuming them, are fundamental steps in starving these bacteria and protecting your enamel shield. It’s not just the quantity of sugar, but the frequency of exposure that dramatically increases the risk. Think of it as repeated small acid attacks throughout the day versus one larger one followed by cleanup time. This frequent exposure is the key driver, making consistent dietary choices and timely cleaning paramount in the battle against sugar-fueled decay.

Cavity Causes and Risk Factors Explained

Beyond the core trio of bacteria, sugar, and acid, several other factors conspire to increase your vulnerability to cavities. Think of them as weakening the defenses or accelerating the attack. First off, let’s talk about plaque itself. It’s a sticky biofilm that constantly forms on your teeth. If plaque isn’t removed regularly and thoroughly through brushing and flossing, it thickens, providing a safe haven for bacteria to multiply and produce more acid, concentrated right against your enamel. So, poor oral hygiene is a huge, gaping risk factor. Frequency of eating and drinking, especially fermentable carbohydrates, is another critical one. Every time you expose your teeth to sugars or starches, you initiate an acid-producing cycle. Constant grazing means constant acid attacks, giving your enamel no chance to recover. Dry mouth, or xerostomia, is a major player you might not immediately think of. Saliva isn’t just wet stuff; it’s a superhero of oral defense. It helps wash away food debris, neutralizes acids, and contains minerals that can help repair early demineralization (remineralization). Conditions like Sjogren’s syndrome, diabetes, or certain medications (antihistamines, decongestants, painkillers, diuretics, and antidepressants are common culprits) can reduce saliva flow, leaving your teeth much more exposed and vulnerable to acid attacks. Eating disorders, particularly those involving vomiting (like bulimia), expose teeth to powerful stomach acids which can cause severe erosion and decay. Your diet’s content matters too – highly acidic foods and drinks (like citrus fruits, sodas, sports drinks) can directly erode enamel, even without bacterial action, making the teeth weaker and more susceptible to subsequent acid attacks from bacteria. Teeth that have deep grooves or pits (especially molars and premolars) are harder to clean effectively, making them natural traps for plaque and food particles and thus more prone to decay. Lack of sufficient fluoride exposure is a significant risk. Fluoride is a mineral that strengthens enamel, making it more resistant to acid attacks and promoting remineralization. If you don’t use fluoride toothpaste, drink fluoridated water, or receive professional fluoride treatments, your enamel is weaker than it could be. Age can also be a factor; older adults may experience gum recession, exposing the tooth roots (which are softer than enamel) to decay, or have reduced saliva flow due to medication or health conditions. Dental restorations like fillings or crowns can sometimes have margins that aren’t perfectly sealed, creating tiny gaps where bacteria and food can hide, leading to decay underneath or around the restoration. Even factors like heredity might play a small role in enamel strength or tooth shape. It’s clear that cavity risk isn’t just one thing; it’s a confluence of diet, hygiene, biology, and even lifestyle choices, all combining to create an environment where decay can flourish, highlighting the importance of a holistic approach to prevention.

What Are the Symptoms and Signs of Cavities?

Now, let’s talk about how your body tries to tell you something’s up, or sometimes, how it doesn’t. One of the truly sneaky things about cavities is that they often start silently. In their earliest stages, when the decay is confined to the outer enamel layer, you might not feel a thing. No pain, no sensitivity, nothing obvious to see unless you’re looking very closely – or a dentist spots it on an X-ray. This is why regular dental check-ups are so critical; they can catch problems before they become symptomatic. As the decay progresses deeper into the tooth, breaching the enamel barrier and reaching the softer dentin underneath, that’s usually when symptoms begin to appear. Dentin contains microscopic tubules that lead towards the pulp, where the tooth’s nerves reside. When acid or temperature changes reach these tubules, they can irritate the nerves, leading to sensitivity. This might manifest as a sharp twinge or discomfort when you eat or drink something hot, cold, or sweet. The sensitivity might be mild at first, maybe just a fleeting moment, but as the cavity deepens, it can become more pronounced and persistent. As the decay eats further into the tooth, a visible sign might emerge – a small pit, a brown or black spot, or even a noticeable hole. You might feel a rough edge with your tongue. Sometimes, trapped food particles in the cavity can cause localized discomfort or pressure. Pain, often described as a toothache, usually signifies that the decay has reached the pulp, causing inflammation of the nerve tissue within. This pain can range from dull and throbbing to sharp and severe, and it might worsen when you bite down or expose the tooth to extreme temperatures. It can also be spontaneous, starting seemingly out of nowhere, and might be particularly troublesome at night. Beyond pain and sensitivity, other potential signs include bad breath (halitosis) and a foul taste in your mouth, which can result from the bacteria and decaying tooth structure within the cavity. The tooth might become discolored, appearing brown or black, although not all discoloration indicates a cavity. Ultimately, the symptoms vary widely depending on the size and depth of the cavity. A small, early cavity might be completely asymptomatic, while a large, deep one can cause excruciating pain. Never wait for pain to seek dental attention; it’s often a sign that the problem is already quite advanced and requires professional care to prevent further complications and preserve the tooth.

What are the Signs of Cavities?

Before pain sets in, your mouth might be trying to give you subtle hints. Knowing what to look for can make a significant difference in catching cavities early when they are easier to treat and potentially even reverse. The very first visible sign of decay isn’t usually a hole, but rather a change in the appearance of the enamel. This often starts as a white spot on the tooth surface. These white spots indicate an area where the enamel has lost minerals (demineralization) but hasn’t yet broken down completely. It’s a sign that the enamel is weakened and vulnerable, a sort of pre-cavity lesion. While these white spots can sometimes be arrested or even remineralized with good oral hygiene and fluoride, they are a clear indicator that the acidic environment is winning and intervention is needed. As the decay progresses, these white spots can turn light brown, then darker brown or even black, indicating further mineral loss and breakdown of the enamel structure. You might then start to notice a visible pit or hole forming, particularly in the chewing surfaces of back teeth or the sides of teeth. Sometimes, the surface might look intact, but the decay is spreading underneath the enamel, a process called undermined enamel. In these cases, the enamel might look discolored or feel soft when examined by a dentist. You might also feel a rough spot or edge on the tooth with your tongue that wasn’t there before. Another early sign, which often precedes pain, is heightened sensitivity to temperature or sweetness. This happens when the decay has just barely penetrated the enamel and reached the outer layer of the dentin, allowing external stimuli to irritate the underlying nerve pathways. While not always a cavity, persistent sensitivity definitely warrants a dental check. Keep an eye out for any unusual discoloration, texture changes, or spots on your teeth. These visual cues, even without accompanying pain, can be critical early warning signals that decay is beginning to take hold and requires attention from a dental professional. Recognizing these signs early is your best defense against more extensive damage.

Do Cavities Cause Bad Breath or Smell?

Absolutely. It’s one of the less-talked-about, but definitely noticeable, potential side effects of a developing cavity. While bad breath, or halitosis, can be caused by many things – diet, dry mouth, gum disease, or even issues elsewhere in the body – an active cavity is certainly a possible culprit. Here’s why: a cavity is, at its core, a damaged, often open area in your tooth. This damaged area becomes a perfect little trap for food particles, bacteria, and decaying tissue. Bacteria, especially those involved in the decay process and other anaerobic bacteria (those that thrive in low-oxygen environments), tend to produce volatile sulfur compounds (VSCs) as they break down food debris and tissue. These VSCs are notorious for their foul, often sulfurous smell, the characteristic odor of bad breath. Think of the smell of rotten eggs – that’s VSCs at work. Inside a cavity, trapped food and plaque are actively decomposing, providing a constant source for these odor-producing bacteria. Furthermore, the decay itself involves the breakdown of tooth structure, and the necrotic (dying) tissue within the cavity can also contribute to an unpleasant odor. So, yes, if you notice persistent bad breath that doesn’t seem to improve much with brushing, or you detect a foul taste originating from a specific tooth, it could definitely be a sign that a cavity is present and acting as a breeding ground for odor-causing bacteria and decomposing material. It’s not the cavity itself that smells, but the microbial activity and trapped debris within it. This symptom, often coupled with one of the others like sensitivity or a visible spot, reinforces the need for a dental examination to identify and address the source of the problem. Addressing the underlying cavity is the only way to eliminate this specific cause of halitosis.

What Does a Cavity Feel Like?

The sensation of a cavity is a bit of a chameleon, changing depending on its size and depth. In its earliest stages, a cavity feels like… well, nothing at all. The enamel is hard and has no nerves, so decay confined to this outer layer is typically asymptomatic. You might only discover it during a routine dental check-up or when your tongue catches on a slightly rough spot that wasn’t there before. As the decay progresses into the dentin, which is softer and contains those microscopic tubules leading to the pulp, that’s when you might start to feel something. The most common sensation at this stage is sensitivity. This is often triggered by temperature changes (hot liquids like coffee, cold drinks or ice cream, even cold air inhaled through the mouth) or by sweet foods and drinks. The feeling might be a quick, sharp twinge, or a brief ache that disappears once the stimulus is removed. It’s often localized to the affected tooth, but sometimes it can be hard to pinpoint exactly which tooth is the culprit. The sensitivity might be mild initially but can become more intense or linger longer as the cavity gets deeper. If the decay continues unchecked and reaches the pulp chamber, where the nerves and blood vessels reside, the pain escalates significantly. This is when you experience a true toothache. The pain can be constant and throbbing, sharp and shooting, or worsen significantly when pressure is applied to the tooth (like biting down). Heat, in particular, tends to aggravate pulpitis (inflammation of the pulp), leading to intense pain. Sometimes, the pain can radiate to the jaw, ear, or temple. Paradoxically, in some very advanced cases where the pulp tissue has died due to overwhelming infection, the intense sensitivity might disappear, but a different kind of pain might arise – pressure and swelling around the root of the tooth as an abscess forms. So, the feeling of a cavity ranges from completely undetectable to mild sensitivity, to moderate discomfort when exposed to certain stimuli, to severe, persistent, or throbbing toothache, sometimes accompanied by swelling or a bad taste. The absence of pain doesn’t rule out a cavity; it just means it might not have reached the most sensitive layers yet, emphasizing the need for regular dental check-ups regardless of symptoms.

The Appearance, Stages, and Types of Tooth Cavities

Tooth decay isn’t a single event; it’s a journey, a progressive dismantling of your tooth’s structure that unfolds over time, and its appearance changes dramatically along the way. Understanding these stages is key to knowing how serious a cavity might be and what kind of intervention is needed. The process begins invisibly at the microscopic level with demineralization, the loss of minerals from the enamel surface. Visually, this often first appears as a white spot, indicating the enamel is porous and weakened. At this very early stage, the decay process might actually be reversible through remineralization if conditions improve (better hygiene, fluoride exposure). If the demineralization continues, the white spot will likely turn brownish or black, signaling that the enamel structure is starting to break down, and a surface lesion is forming. This is when a true, though possibly still very small, cavity begins. From there, the decay progresses inwards, breaching the enamel and entering the dentin. Dentin is softer than enamel, so the decay tends to spread more rapidly once it reaches this layer. As the cavity expands in the dentin, it often creates a larger area of decay underneath a smaller opening in the enamel – like a mushroom shape. Visually, this might appear as a larger brown or black area, and a noticeable hole might be present. The surface of the tooth around the decay might feel soft or crumbly when probed gently. If left untreated, the decay will continue its relentless march towards the pulp, the innermost part of the tooth containing nerves and blood vessels. Decay reaching the pulp is a significant problem, often leading to severe pain, infection, and potentially an abscess. At this advanced stage, a large, often visible hole is typically present, and the tooth structure may be significantly compromised. The appearance also depends on the type of cavity, which is often classified by where it occurs on the tooth. Pit and fissure cavities form on the chewing surfaces of back teeth (molars and premolars) and the back of front teeth, areas with natural grooves that trap plaque. Smooth surface cavities form on the flat exterior surfaces of teeth, usually where plaque is not effectively removed, often between teeth. Cavities between teeth (called interproximal cavities) are tricky because you can’t see them easily, and they require flossing to remove the plaque that causes them. Dentists often rely on X-rays to detect these hidden smooth surface cavities. Root cavities occur on the root surface of the tooth, below the gum line, and are common in older adults with gum recession; root surfaces are covered by cementum, which is even softer than dentin, making these cavities progress very quickly. A specific form, Early Childhood Caries (ECC), formerly known as baby bottle tooth decay, affects very young children. It’s often severe and rapidly progressive, typically affecting the upper front teeth first. It’s strongly associated with prolonged exposure to sugary liquids, such as sleeping with a bottle containing milk or juice, or frequent sipping of sugary drinks from a sippy cup throughout the day. Each type presents slightly differently and may require different treatment approaches, underscoring the importance of a dentist’s expertise in diagnosis and management.

What Does a Stage 1 Cavity Look Like?

Ah, the sneaky beginnings! A Stage 1 cavity, or more accurately, an initial or early lesion of tooth decay, often doesn’t look like a cavity at all in the traditional sense of a black hole. Instead, the classic appearance of early enamel demineralization, which is the very first stage of the decay process before a cavity truly forms, is a **white spot lesion**. Imagine the tooth surface losing its translucency and uniformity; it starts to look dull or chalky white in a specific area. These white spots typically appear just below the surface of the enamel. They represent areas where the acidic environment created by plaque bacteria has dissolved calcium and phosphate minerals from the enamel’s crystalline structure. The enamel is still intact on the surface, but beneath it, the porous structure reflects light differently, making the spot appear opaque white. These white spot lesions are often easier to see when the tooth surface is dried; when wet with saliva, they can be less apparent. They can occur on any tooth surface, but are commonly seen near the gum line, particularly on the front teeth, and around orthodontic brackets. While technically not yet a cavity (a physical hole), they are a strong indicator that the decay process is active and that if left unaddressed, the enamel surface will eventually break down, leading to a proper cavity (a Stage 2 or beyond lesion). The critical thing about the white spot stage is that it is potentially reversible. With diligent oral hygiene, increased fluoride exposure (through fluoride toothpaste, mouthwash, or professional application), and dietary changes to reduce sugar frequency, the minerals can be redeposited into the weakened enamel structure, essentially healing the lesion before a hole forms. So, if you spot a suspicious white area on your tooth, don’t dismiss it – it’s your tooth waving a tiny, white flag of distress, signalling a critical point where intervention can prevent a cavity from forming. It requires careful monitoring and proactive steps to encourage remineralization and arrest the decay process at this early stage, ideally under the guidance of a dental professional who can assess the lesion and recommend the most effective strategies for reversal or management.

What Does a Stage 3 Cavity Look Like?

By the time a cavity reaches Stage 3, or more generally, a moderate to advanced stage of decay, it’s usually moved well beyond the subtle white spot. This is often what people picture when they hear the word “cavity.” A Stage 3 cavity typically means the decay has progressed through the outer enamel layer and significantly into the underlying dentin. At this point, the appearance is usually quite noticeable. You’re likely looking at a visible **hole or pit** in the tooth surface. The size of the hole can vary – it might still be relatively small on the enamel surface, but the decay can have spread laterally within the softer dentin underneath, creating a larger area of damage below the surface. The color of the decayed area is usually dark – **brown, dark brown, or black**. This discoloration comes from staining of the demineralized and damaged tooth structure by food, drinks, and bacterial byproducts, as well as the physical breakdown of the dentin itself. The texture around the cavity will likely feel soft or crumbly to the touch (though you shouldn’t probe it yourself!). You might feel a definite indentation or snag with your tongue when you run it over the tooth surface. In some cases, a large portion of the tooth structure might appear missing or hollowed out. If the cavity is on a chewing surface, it might look like a dark, sunken area in the grooves. If it’s between teeth, it might only be visible on an X-ray, or you might see a dark shadow through the enamel on the side of the tooth, or feel a definite catch when flossing. A Stage 3 cavity is past the point of simple reversal with hygiene and fluoride; it represents a significant structural defect in the tooth. It usually requires professional dental intervention, most commonly a filling, to remove the decayed tissue and restore the tooth’s shape and function. Waiting at this stage allows the decay to continue its advance towards the pulp, increasing the risk of pain, infection, and the need for more complex treatment like a root canal. Timely treatment is crucial to prevent these more severe complications and preserve the tooth structure.

Types of Cavities You Can Get

Cavities aren’t a one-size-fits-all problem; they are classified based on where they form on the tooth surface, which often relates to how they start and how they are treated. Understanding the different types helps explain why some cavities are easy for your dentist to spot while others remain hidden. The most common type is **Pit and Fissure Caries**. These form in the chewing surfaces of your back teeth (molars and premolars) and sometimes on the back surface of your front teeth. These areas have natural grooves and pits that are notoriously difficult to clean thoroughly with a toothbrush, making them ideal hiding spots for plaque, food particles, and acid-producing bacteria. Decay here often starts invisibly deep within the fissure and spreads outwards. **Smooth Surface Caries** occur on the flat, smooth exterior surfaces of the teeth. These are less common than pit and fissure cavities in adults, but they can develop in areas where plaque isn’t removed effectively, particularly along the gum line or, very commonly, between teeth. Cavities between teeth (called interproximal cavities) are tricky because you can’t see them easily, and they require flossing to remove the plaque that causes them. Dentists often rely on X-rays to detect these hidden smooth surface cavities. **Root Caries** develop on the tooth root surface. This surface is normally protected by gum tissue. However, if your gums recede (due to gum disease, aggressive brushing, or age), the root surface, which is covered by a softer material called cementum, becomes exposed. Cementum decays much faster than enamel, so root cavities can progress rapidly and are a significant concern, especially for older adults. A specific form, Early Childhood Caries (ECC), formerly known as baby bottle tooth decay, affects very young children. It’s often severe and rapidly progressive, typically affecting the upper front teeth first. It’s strongly associated with prolonged exposure to sugary liquids, such as sleeping with a bottle containing milk or juice, or frequent sipping of sugary drinks from a sippy cup throughout the day. Understanding these different types helps dentists diagnose and treat cavities effectively, recognizing the distinct challenges each type presents and tailoring treatment and prevention strategies accordingly.

Dealing with Pain from Tooth Cavities

Okay, let’s cut to the chase: tooth pain. For many, this is the symptom that finally sends them scrambling for a dental appointment. And for good reason – when a cavity starts to hurt, it usually means the decay has reached a critical point. Pain from a cavity isn’t just random discomfort; it’s a clear signal that the decay has breached the outer, non-sentient layers (enamel and potentially much of the dentin) and is now irritating or infecting the dental pulp, the living core of the tooth containing nerves, blood vessels, and connective tissue. The pulp is highly sensitive, and when it becomes inflamed due to bacterial invasion or irritation from temperature changes reaching the deeper layers, it sends pain signals. This condition is called pulpitis. Initially, the pain might only occur when triggered by hot, cold, or sweet stimuli, because the fluid movement within the dentinal tubules or direct contact with temperature changes excites the nerve endings in the pulp. But as the inflammation increases and the infection potentially sets in, the pain can become spontaneous – starting without any external trigger – and persistent. It might be a dull ache, a sharp throbbing, or an intense, unbearable sensation, often worsening when you lie down or at night because of increased blood flow to the head. Pain also signifies that the cavity is now past the point of being reversible or treatable with just a simple filling; depending on the severity of the pulp involvement, it might require a root canal or even extraction. While you might desperately seek immediate relief, and there are certainly home remedies and over-the-counter options that can help manage the pain temporarily, it is absolutely crucial to understand that these do not address the underlying problem. Popping painkillers or rinsing with salt water will numb the signal, but the decay and potential infection are still advancing within the tooth. Relying solely on pain relief is like ignoring the smoke alarm while the house is burning down. Therefore, while you might need to manage the discomfort until you can see a dentist, pain from a cavity is a siren call urging you to seek professional treatment promptly. It signals a more advanced stage of decay that needs expert attention to save the tooth and prevent complications. Don’t underestimate the significance of tooth pain; it’s your body telling you it’s time to act.

Why Is a Cavity Painful?

The architecture of your tooth holds the key to understanding cavity pain. The outermost layer, the enamel, is the hardest substance in your body and contains no nerves, making it impervious to pain. You can have decay completely eroding your enamel, and you might not feel a thing. Beneath the enamel lies the dentin, a softer layer composed of tiny tubules stretching from the enamel-dentin junction inwards towards the pulp. These tubules contain fluid and cellular extensions from the pulp. Dentin itself has some sensitivity, but the intense pain associated with cavities primarily comes from the pulp. The dental pulp is the living tissue at the center of the tooth, housed within the pulp chamber and root canals. It’s rich in blood vessels, connective tissue, and crucially, nerves. When a cavity penetrates through the enamel and reaches the dentin, particularly as it gets closer to the pulp, external stimuli like hot, cold, or sweet foods and drinks can travel through those dentinal tubules and irritate the nerves in the pulp. This irritation causes inflammation of the pulp, a condition known as pulpitis. Initially, if the pulp is only mildly inflamed and the cause (like a cold drink) is removed, the pain subsides quickly (reversible pulpitis). However, as the decay gets deeper, potentially allowing bacteria to enter the pulp, the inflammation becomes more severe and irreversible (irreversible pulpitis). This causes sustained pressure within the confined pulp chamber due to swelling, and the nerves become highly sensitized and constantly irritated. This leads to the classic toothache pain – throbbing, constant, or spontaneous discomfort that doesn’t go away, even after the stimulus is removed. In essence, the pain signifies that the infection and decay have reached the tooth’s nerve center, triggering a protective response that, unfortunately, manifests as significant discomfort. It’s the tooth’s way of screaming for help because its vital core is under attack and requires professional intervention to resolve the infection and prevent further damage. Understanding this process reinforces why cavity pain is a symptom that should never be ignored.

How to Stop Cavity Pain at Night?

Toothache often seems to worsen when you’re trying to sleep. This isn’t just bad luck; it’s partly due to physiological changes. When you lie down, blood flow to your head increases, which can heighten the pressure within the inflamed pulp of the tooth, intensifying the pain. Plus, without the distractions of the day, you’re simply more aware of the discomfort. While waiting for a dental appointment (which is crucial for definitive treatment), there are a few strategies that might offer temporary relief and help you catch some much-needed rest. Firstly, elevating your head with an extra pillow can help reduce some of that blood flow and pressure in the head, potentially easing the throbbing pain. Over-the-counter pain relievers are often the most effective immediate measure. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin) or naproxen (Aleve) are particularly good because they help reduce inflammation as well as block pain signals. Acetaminophen (Tylenol) can also help with pain, but it doesn’t reduce inflammation. Make sure to follow the dosage instructions on the packaging. Topical pain relievers, such as gels or liquids containing benzocaine (like Orajel), can be applied directly to the affected tooth and surrounding gum tissue to numbs the area, providing localized relief. However, be cautious with these; they are only for temporary use and shouldn’t be applied to open wounds or for extended periods. Rinses are also helpful. Rinsing your mouth with warm salt water can be soothing. Mix half a teaspoon of salt in a glass of warm water and swish it around your mouth, then spit it out. This can help reduce swelling and clean out debris around the tooth. A cold compress or ice pack applied to the outside of your cheek over the painful area might help numb the pain and reduce swelling; don’t apply ice directly to the tooth itself, as temperature sensitivity might worsen the pain. Avoid hot foods or drinks, which can exacerbate pulpitis pain. Also, avoid lying on the side of the painful tooth. While these methods offer temporary respite, remember they are not a cure. Cavity pain at night usually indicates a significant problem that requires professional dental treatment as soon as possible. Don’t delay seeing a dentist; these are just stop-gap measures.

How to Reduce Toothache at Home?

When toothache strikes, the immediate instinct is often to find a quick fix using whatever’s available at home. While no home remedy can cure a cavity or replace professional dental treatment, some methods can help alleviate the pain temporarily while you wait to see a dentist. As mentioned for night pain, over-the-counter pain relievers are your most reliable first line of defense. NSAIDs like ibuprofen are often recommended due to their anti-inflammatory properties, which target the underlying cause of pulp-related pain. Acetaminophen can also help with pain relief. Always follow the dosage instructions carefully. Rinsing with warm salt water (half a teaspoon of salt in a glass of warm water) is a classic and often effective remedy. It helps cleanse the area, reduce swelling, and can draw out some fluid, potentially easing pressure. Swish gently and spit. Some people find relief using a cold compress or ice pack applied to the outside of the cheek near the affected tooth for 15-20 minutes at a time. This can help numb the area and reduce inflammation. Be sure to wrap the ice in a cloth; don’t apply it directly to your skin or, critically, to the tooth itself if it’s sensitive to cold. Clove oil is another traditional remedy. It contains eugenol, a natural anesthetic and antiseptic. You can apply a tiny amount of clove oil to a cotton swab and dab it gently on the painful tooth and surrounding gum. Be careful, as it can have a strong taste and may irritate soft tissues if too much is used or if it contacts the gums excessively. Some people chew on a whole clove near the tooth. However, use clove oil sparingly and ensure it’s food-grade. Avoid remedies that haven’t been proven effective or could cause harm, such as placing aspirin directly on the gum (it’s acidic and can cause chemical burns). While these home methods can offer a temporary truce with the pain, they are not solutions for a cavity. They cannot remove decay or fill the hole. Use them as a stopgap measure and prioritize getting to a dentist as soon as possible. Delaying professional treatment will only allow the decay to worsen and the problem to become more complex and painful in the long run. Seek professional help; home remedies are not a substitute for treatment.

Do Cavities Always Hurt?

This is a crucial point to understand: **No, cavities do not always hurt.** In fact, many cavities, especially in their early stages, are completely painless. This is precisely why relying on pain as the sole indicator of a dental problem is a dangerous game to play with your oral health. When decay is limited to the outer enamel layer, there are no nerves involved, so there’s no sensation of pain. You might have a significant amount of demineralization or even a small enamel-only cavity forming, and be totally unaware of it. The only way these early, asymptomatic cavities are typically detected is through regular dental check-ups, where a dentist uses visual examination, probing the tooth surface, and taking X-rays. X-rays are particularly vital as they can reveal cavities forming between teeth or underneath existing fillings, areas invisible during a routine visual exam. Pain usually doesn’t begin until the decay has eaten its way through the enamel and started to penetrate the underlying dentin, which is more sensitive, or, more significantly, when it reaches the pulp, the nerve center of the tooth. By the time you experience pain, the cavity is often already moderately to severely advanced. This means the treatment required might be more involved (like a root canal) compared to a simple filling needed for an earlier-stage cavity. Furthermore, sometimes even very large cavities might cause intermittent pain or no pain at all if the pulp has already died due to chronic infection – in such cases, an abscess might form, causing different symptoms like swelling and persistent pressure. So, the absence of pain is not a green light to skip dental visits. It simply means the decay hasn’t hit a nerve (yet), emphasizing the importance of regular check-ups for early detection and intervention. Regular dental check-ups are your best defense against silent, progressing cavities; don’t wait for pain to see your dentist.

If a Cavity Hurts, Is It Too Late?

The onset of pain from a cavity is certainly a wake-up call, a sign that the decay is no longer superficial. It indicates that the infection or inflammation has likely reached the dentin and is getting close to or has entered the pulp (the tooth’s nerve). While the pain signifies a more advanced stage of the cavity, it does *not* automatically mean it’s too late to save the tooth. Think of it as reaching a critical point, but often not a point of no return regarding tooth preservation. If the pain is due to inflammation of the pulp (pulpitis), a dentist will assess if the pulp is reversibly or irreversibly inflamed. If caught early enough, sometimes simply removing the decayed tissue and placing a filling can allow the pulp to recover (reversible pulpitis). More often, if the pain is significant and persistent, it indicates irreversible pulpitis, where the pulp is too damaged or infected to heal on its own. In these cases, the treatment required is typically a root canal. This procedure involves removing the infected or inflamed pulp tissue from within the tooth, cleaning and disinfecting the root canal system, and then filling and sealing the space. After a root canal, the tooth often needs a crown to protect the weakened structure. While more complex and costly than a filling, a root canal is a way to save the tooth and eliminate the infection and pain, avoiding extraction. Extraction is usually considered a last resort, necessary only when the tooth is too severely damaged by decay or fracture to be restored, or if an infection has spread extensively and cannot be resolved with root canal therapy. So, while pain signals that the decay is advanced and the necessary treatment might be more involved than a simple filling, it’s usually *not* too late to save the tooth with procedures like a root canal. However, it’s a clear indication that you need to see a dentist *immediately* to get a proper diagnosis and initiate treatment to prevent further complications and determine the best course of action for preserving your natural tooth if possible. Delaying care once pain begins significantly reduces the chances of saving the tooth and increases the risk of serious infection spreading, potentially leading to tooth loss.

Can a Tooth Cavity Heal or Be Cured on Its Own?

Let’s address one of the most common questions and, sadly, one of the most persistent myths surrounding dental health: the idea that a tooth cavity can heal itself. The short, definitive answer is **no, an established tooth cavity (a hole in the tooth structure) cannot heal on its own**. Once the enamel surface is physically broken, creating a cavity, that structural loss is permanent. Unlike bones, which can knit themselves back together, or skin, which can regenerate tissue, tooth enamel and dentin don’t have living cells that can reproduce and repair a significant structural defect. The tooth is mineralized tissue, and while the very earliest stages of demineralization on the enamel surface (those white spots we discussed) can be reversed or arrested through remineralization (the process where minerals are redeposited into the enamel), this only works before a true hole forms. Once the surface barrier is breached and the decay has created a physical cavity, the natural repair mechanisms of the mouth, like saliva and fluoride, are no longer sufficient to rebuild the missing tooth structure. In fact, if left untreated, the decay process will continue its advance into the tooth, making the cavity larger and deeper over time. Think of it like a pothole forming in a road; you can’t just wait for it to fill itself in. It requires intervention – someone needs to fill it with new material. Similarly, an established cavity requires professional dental treatment, most commonly a filling, to remove the decayed material, clean the affected area, and restore the tooth’s form and function with a restorative material like composite resin, amalgam, or ceramic. More extensive cavities may require crowns, root canals, or even extraction if the tooth is too severely damaged. So, while you can take steps to *stop* the decay process from progressing at the very earliest white spot stage, and you can certainly prevent *new* cavities from forming, you cannot reverse or “cure” a cavity once a physical hole has developed through natural means alone. Any claims of home remedies or natural methods that can magically heal a cavity are simply untrue and potentially harmful, as delaying necessary professional treatment allows the decay to worsen significantly and increases the risk of severe complications.

Can a Cavity Heal on Its Own?

No, let’s be unequivocally clear: **a true tooth cavity, meaning a hole or structural defect in the enamel or dentin, cannot heal on its own.** The process of tooth decay involves the loss of mineral structure from the tooth surface, followed by the physical breakdown of that weakened material, creating a void – the cavity. Human teeth, particularly the enamel and dentin which form the bulk of the tooth’s structure, are not living tissues in the same way that skin or bone are. They are highly mineralized tissues with limited cellular components that cannot regenerate lost structure once it’s gone. The mouth does have natural defense mechanisms, primarily saliva, which contains minerals like calcium and phosphate and helps neutralize acids. Fluoride, whether from toothpaste, water, or dental treatments, also plays a critical role in strengthening enamel and promoting remineralization. These natural and preventative tools are highly effective at *preventing* cavities from forming in the first place, and they can even help to *arrest* or *reverse* very early-stage decay when it’s just a microscopic loss of minerals from the enamel surface (a white spot) and hasn’t yet caused a physical break in the enamel. This process of remineralization can repair the porous, demineralized enamel. However, once the acid attack has progressed to the point of causing a macroscopic breakdown – a visible pit, lesion, or hole – the tooth cannot rebuild that missing structure. The cavity is a permanent defect that will only get larger and deeper over time if left untreated. Think of it as a crack in a windowpane; the window cannot repair itself. It needs patching or replacement. Similarly, a cavity needs patching (a filling) or other restorative work by a dental professional. Any assertion that you can heal a cavity with diet, supplements, or other home methods once a hole has formed is medically inaccurate and dangerous, as it encourages delaying the necessary treatment, leading to potential complications and tooth loss. Professional dental care is the only effective “healing” for an established cavity.

Can Tooth Cavity Be Cured?

Yes, tooth cavities can be “cured,” but the definition of “cured” here means **repaired and treated by a dental professional**. It doesn’t mean the tooth magically regenerates the lost tissue. A cavity is cured by stopping the decay process in that specific area, removing the damaged tooth structure, and restoring the tooth with a filling or other restoration. This involves a dental professional cleaning out all the decayed material from the cavity, disinfecting the prepared space, and then filling the cavity with a material designed to restore the tooth’s strength, shape, and function. Common filling materials include composite resin (tooth-colored plastic and glass mixture), amalgam (a silver-colored alloy), gold, or porcelain. The type of filling used depends on the size and location of the cavity, as well as cost considerations. For larger cavities that have weakened a significant portion of the tooth structure, a crown (a cap that covers the entire tooth) might be needed after removing the decay to protect the tooth from breaking. If the decay has reached the pulp, the tooth requires a root canal procedure to remove the infected nerve tissue before it can be restored. In very severe cases where the tooth is extensively damaged and cannot be saved, extraction (removing the tooth) is the only option, after which replacement with an implant, bridge, or denture might be considered. So, while the tooth itself cannot heal the cavity, the cavity can be *treated* or *cured* through professional dental procedures that remove the disease (the decay) and repair the damage (the hole). This intervention stops the progression of the decay in that tooth and restores its integrity, effectively curing the immediate problem with that specific cavity. However, curing one cavity doesn’t make you immune to future cavities; preventing those requires ongoing good oral hygiene and preventative care. Think of the filling or crown as the “cure” – it fixes the problem and prevents it from continuing to worsen in that spot.

Can You Fix a Stage 1 Cavity?

This is where the nuance comes in! While a true hole (a cavity) cannot heal itself, you *can* potentially fix, reverse, or arrest the progression of a very early-stage lesion, often referred to as a **Stage 1 cavity** or an **initial lesion** or **white spot lesion**. At this earliest point, the decay process has only just begun to demineralize the enamel. The enamel surface is still largely intact, but the subsurface has become porous due to mineral loss, appearing as that characteristic chalky white spot. This stage is a critical window of opportunity because the process *can* be reversed or stopped *before* it progresses to a cavitation (the formation of an actual hole). How is this “fixed”? Primarily through remineralization. This involves strengthening the enamel by promoting the redeposition of minerals like calcium, phosphate, and fluoride back into the weakened structure. The key strategies for fixing a Stage 1 lesion are: **Increased Fluoride Exposure:** Using a fluoride toothpaste twice a day is essential. Your dentist might also recommend a higher-concentration prescription fluoride toothpaste, a fluoride mouth rinse, or in-office fluoride varnish treatments. Fluoride makes the enamel crystals more resistant to acid attacks and actively helps attract minerals back into the weakened areas. **Improved Oral Hygiene:** Regular and thorough brushing and flossing remove the plaque containing the acid-producing bacteria and food debris, thereby reducing the frequency and intensity of acid attacks. **Dietary Changes:** Reducing the frequency of consuming sugary and acidic foods and drinks limits the fuel source for bacteria and reduces direct acid erosion, allowing the mouth’s pH to recover between meals. **Saliva Stimulation:** Chewing sugar-free gum can stimulate saliva flow, helping to neutralize acids and aid remineralization. **Regular Dental Monitoring:** Your dentist can monitor the white spot lesion over time to ensure it’s not progressing and recommend targeted preventative measures. If these steps are successful, the enamel can reharden, and the white spot might even become less noticeable or disappear entirely. However, if the white spot continues to progress and the enamel surface breaks down, forming a true cavity, then professional restorative treatment (a filling) becomes necessary, as the point of natural reversal has passed. So, yes, you can often fix a Stage 1 cavity, but it requires proactive measures to stop the decay process and encourage the tooth to remineralize, rather than just waiting for it to disappear on its own. This early intervention is the closest thing to “healing” a cavity naturally.

Preventing Tooth Cavities

Alright, enough talk of holes and decay. Let’s shift gears to the good stuff: keeping cavities from crashing the party in the first place! Preventing cavities is infinitely better, simpler, and cheaper than treating them. It’s a proactive approach, building a strong defense against the bacterial invaders and acid attacks. The cornerstones of cavity prevention are surprisingly straightforward, centering on consistent, mindful oral care. It starts, of course, with **excellent daily oral hygiene**. This means brushing your teeth thoroughly twice a day, ideally in the morning and before bed, using a fluoride toothpaste. Proper brushing technique involves cleaning all surfaces of the teeth, including the front, back, and chewing surfaces, and paying attention to the area along the gum line where plaque tends to accumulate. Equally vital is **daily flossing** (or using interdental brushes). Brushing alone cleans only about 60% of your tooth surfaces; flossing is essential for removing plaque and food particles from between your teeth, areas where cavities commonly form and are hard to detect visually. The role of **fluoride** cannot be overstated. Fluoride is a natural mineral that significantly strengthens tooth enamel, making it more resistant to acid attacks. It also promotes remineralization, helping to repair early demineralization before a cavity forms. Ensure your toothpaste contains fluoride. Drinking fluoridated tap water (if available in your area) is another effective way to get consistent, low-level fluoride exposure. Your dentist might also recommend professional fluoride treatments (varnishes or gels) during your check-ups, particularly if you are at higher risk for cavities. **Your diet** plays a massive role. Limiting the frequency of consuming sugary and starchy foods and drinks reduces the fuel available for acid-producing bacteria. Instead of grazing on sugary snacks or sipping on soda throughout the day, try to consume these items less frequently and, if possible, rinse your mouth with water afterward. Choosing healthier snacks like fruits (in moderation, as they contain natural sugars and acids, but with fiber that helps clean teeth), vegetables, cheese, or plain yogurt is better for your teeth. Staying hydrated, especially with water, helps maintain good saliva flow, aiding in cleansing and acid neutralization. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, **regular dental check-ups and professional cleanings** are indispensable. Your dentist and dental hygienist can remove hardened plaque (calculus or tartar) that you can’t remove with brushing and flossing, identify early signs of decay (like white spots) before they become cavities, apply protective sealants to vulnerable chewing surfaces of back teeth (especially for children and teenagers), and provide personalized advice on improving your oral hygiene routine. They can also assess your individual risk factors and recommend additional preventative measures. Prevention is an ongoing effort, a daily commitment to keeping your mouth healthy, but the rewards – a healthy smile and avoiding the discomfort and cost of treating cavities – are absolutely worth it. It’s the foundation of long-term oral wellness. Source: Preventive Dentistry

How to Avoid Cavities Effectively

Avoiding cavities effectively boils down to consistently implementing a few key strategies that target the root causes: bacteria, acid, and weakened enamel. First, the absolute foundation is **superior oral hygiene**. This means brushing for two minutes, twice daily, with a fluoride toothpaste. Use a soft-bristled brush and ensure you’re cleaning all surfaces – fronts, backs, tops, and along the gumline. Don’t forget to brush your tongue to remove bacteria that contribute to bad breath. Equally non-negotiable is **daily interdental cleaning**. Use dental floss, floss picks, or interdental brushes to clean between *all* your teeth, as this removes plaque and food particles from areas where cavities often start unnoticed. If you find flossing difficult, ask your dental hygienist for tips or alternative tools. Next, **harness the power of fluoride**. Use a toothpaste with fluoride. If your community water supply is fluoridated, drink tap water. Your dentist might recommend fluoride mouth rinses or prescription-strength fluoride toothpaste if you’re at high risk. Professional fluoride treatments during dental visits provide a concentrated boost to enamel strength. **Control your diet, particularly sugar exposure frequency**. It’s not just about how much sugar you eat, but how often. Limit snacking between meals, especially on sugary or starchy foods. If you do indulge, try to do it as part of a main meal. Avoid sipping on sugary drinks (sodas, juices, sweetened teas/coffees, sports drinks) for extended periods. Instead, drink them relatively quickly, and ideally, rinse your mouth with water afterward. Choose water as your primary beverage between meals. **Chewing sugar-free gum** after eating can help stimulate saliva flow, which helps neutralize acids and wash away food particles. Look for gums containing Xylitol, as some studies suggest it may have additional benefits in reducing decay-causing bacteria. Finally, **don’t skip your regular dental check-ups and cleanings**. For most people, this means visiting the dentist every six months. These visits allow professionals to remove hardened plaque, spot early signs of decay or gum disease that you might miss, and provide protective treatments like sealants on molars, which create a barrier over the vulnerable pits and fissures. These combined efforts create a powerful defense system, significantly reducing your risk of developing cavities and preserving your smile for the long term. Consistency in these habits is the most effective strategy.

How to Stop a Cavity From Growing?

Once a true cavity (a physical hole) has formed, you cannot stop it from growing through just brushing and flossing alone. While excellent oral hygiene is absolutely crucial for *preventing* new cavities and keeping the rest of your mouth healthy, it cannot remove the decayed tooth structure that has already broken down. Brushing and flossing will help remove the plaque and food particles that are *feeding* the decay process within the cavity, potentially slowing it down slightly, but they won’t eliminate the decay itself or rebuild the missing tooth material. Think of it this way: if you have rust eating a hole in a piece of metal, cleaning the rust off regularly might slow the progression a little, but it won’t make the hole disappear or prevent the rust from continuing to spread deeper into the metal. To stop a cavity from growing, you need **professional dental intervention**. A dentist must physically remove all the decayed tooth tissue using dental instruments, essentially cleaning out the “infected” part of the tooth. Once the decay is removed, the resulting hole needs to be filled with a restorative material to seal the tooth, prevent bacteria from re-entering and resuming the decay process, and restore the tooth’s structural integrity. The type of restoration needed depends on how far the cavity has progressed. For smaller cavities, a filling is used. For larger cavities that have compromised more tooth structure, a crown might be necessary. If the decay has reached the pulp, a root canal is required to remove the infected tissue before the tooth can be restored. Delaying treatment will allow the decay to continue spreading deeper and wider within the tooth. This not only makes the cavity larger but also increases the risk of the decay reaching the pulp, leading to pain, infection, and potentially the need for more complex (and expensive) procedures like a root canal, or even tooth extraction if the damage is too extensive to repair. So, while maintaining good hygiene is vital for overall oral health, the only way to definitively *stop* an existing cavity from growing is to have it professionally treated by a dentist who can remove the decay and restore the tooth. Prompt treatment is essential.

How Can I Prevent Cavities?

Preventing cavities is a multi-faceted approach, requiring consistent effort and partnership with your dental professional. It’s not about one magic bullet, but a combination of daily habits and regular care. Here is a comprehensive breakdown of how you can effectively prevent cavities: **1. Brush Your Teeth Regularly with Fluoride Toothpaste:** Brush for two minutes, twice a day, using a toothpaste that contains fluoride. Ensure you cover all tooth surfaces and the gumline. **2. Clean Between Your Teeth Daily:** Use dental floss, interdental brushes, or a water flosser to remove plaque and food particles from between teeth where your toothbrush can’t reach. **3. Limit Sugary and Acidic Food and Drink Frequency:** Reduce how often you consume items like candies, cookies, cakes, sodas, fruit juices, sports drinks, and even starchy snacks like chips and bread. If you do consume them, try to do so as part of a meal and ideally rinse your mouth with water afterward. **4. Choose Tooth-Friendly Foods:** Opt for snacks like fresh fruits and vegetables, cheese, nuts, and plain yogurt, which are less likely to promote decay. **5. Drink Fluoridated Water:** If your tap water is fluoridated, make it your primary beverage throughout the day. **6. Use Fluoride Products as Recommended:** Depending on your risk level, your dentist might recommend using a fluoride mouth rinse or a prescription-strength fluoride toothpaste. **7. Consider Dental Sealants:** Discuss dental sealants with your dentist, especially for children and teenagers. These plastic coatings are applied to the chewing surfaces of back teeth to seal off the pits and fissures where decay often starts. More info: Dental Sealants **8. Don’t Skip Regular Dental Check-ups and Cleanings:** Visit your dentist typically every six months (or as recommended) for professional cleanings and examinations. They can identify early signs of decay, provide preventative treatments, and offer personalized advice. **9. Address Dry Mouth:** If you suffer from dry mouth (xerostomia), talk to your dentist or doctor. They can help identify the cause and recommend strategies or products (like artificial saliva or medications) to manage it, as reduced saliva flow significantly increases cavity risk. **10. Maintain Good Overall Health:** Some systemic health conditions can impact oral health, so managing conditions like diabetes is important. By incorporating these steps into your routine, you create a powerful defense system for your teeth, dramatically reducing your chances of developing cavities and maintaining a healthy, pain-free smile for years to come. It’s a lifelong commitment to proactive care.

How Are Cavities Diagnosed by Dentists?

Diagnosing cavities isn’t always as simple as peering into someone’s mouth and spotting a black spot. While advanced cavities can be visually obvious, many others are hidden from plain sight, requiring a professional eye and specialized tools. Dentists use a combination of methods to accurately detect the presence and extent of tooth decay. The process usually begins with a **thorough visual examination** of your teeth. Find out more about Dental Examination. The dentist will look for visible signs of decay, such as white spots (early demineralization), brown or black areas, or noticeable pits and holes on the tooth surfaces. They’ll check the chewing surfaces, the smooth surfaces, and the areas along the gum line. Next, the dentist uses a dental instrument called an **explorer**. This is a slender, pointed metal tool that the dentist uses to gently probe the surfaces of your teeth, especially in the pits and fissures. Healthy enamel and dentin are hard and resistant; if the explorer “sticks” in a groove or pit, or if the tooth surface feels soft or rough in a suspicious area, it can indicate that the enamel has lost its mineral integrity and decay is present. While this probing technique is helpful, dentists rely less on heavy probing in recent years due to the risk of damaging remineralizable enamel; it’s often used more gently now to feel for texture changes. A critical diagnostic tool is **dental X-rays (radiographs)**. These are essential for detecting cavities that cannot be seen during a visual exam, particularly cavities forming between teeth (interproximal cavities) and decay that is developing underneath existing fillings or crowns. Bitewing X-rays, taken periodically, show the upper and lower back teeth in biting position and are excellent for revealing interproximal decay. Periapical X-rays show the entire tooth from crown to root and are useful for assessing decay near the root or detecting abscesses. The X-ray image allows the dentist to see through the outer layers of the tooth and visualize areas of demineralization or structural breakdown that appear as darker areas on the film. Dentists may also use **other diagnostic aids**, such as intraoral cameras (which project magnified images of your teeth onto a screen), special dyes that stain decayed areas, or newer technologies like laser fluorescence devices or digital imaging that can help detect early demineralization. The dentist will combine all this information – your reported symptoms, their visual and tactile findings, and the radiographic evidence – to arrive at a diagnosis. If a cavity is found, they will explain where it is, how large or deep it appears, and recommend the appropriate treatment plan. This multi-pronged approach ensures even hidden decay is identified early.

Cavity Diagnosis: What to Expect at the Dentist

Walking into the dentist’s office for a check-up might feel routine, but the process they follow for cavity diagnosis is a systematic investigation designed to catch problems early. Here’s what typically happens. First, you’ll usually have a **discussion about your medical history, any medications you’re taking, and any changes in your oral health**, including sensitivity, pain, or anything unusual you’ve noticed. This provides the dentist with valuable context. Then, a dental hygienist or the dentist will perform a **professional cleaning** to remove plaque and calculus (hardened plaque) from your teeth. This is important because plaque can hide decay, and a clean surface allows for a more accurate examination. Following the cleaning, the **visual and tactile examination** takes place. The dentist will meticulously look at each tooth surface using a small mirror and good lighting. They’ll look for obvious signs of decay – discoloration (white, brown, or black spots), changes in enamel texture, or visible holes. They will use a gentle explorer instrument to feel the surface, checking for softness or stickiness in pits and fissures that might indicate compromised enamel. They will also examine your gums and other oral tissues. A crucial part of the diagnosis is **taking dental X-rays**. This isn’t done at every single appointment for every patient, but is typically recommended periodically (e.g., annually for bitewings) based on your age, risk factors, and dental history. X-rays are non-negotiable for finding cavities between teeth or under existing restorations, areas impossible to see otherwise. The X-ray image shows the internal structure of the teeth, and decay appears as darker areas because the demineralized tissue is less dense than healthy tooth structure. Depending on the dentist’s practice and your specific needs, they might also use **additional diagnostic tools**, such as intraoral cameras to show you what they’re seeing on a screen, or newer technologies like digital caries detection devices that use light or laser fluorescence to identify early decay that isn’t yet visible or apparent on X-rays. The dentist will combine all this information – your reported symptoms, their visual and tactile findings, and the radiographic evidence – to arrive at a diagnosis. If a cavity is found, they will explain where it is, how large or deep it appears, and recommend the appropriate treatment. This comprehensive approach ensures that both obvious and hidden cavities are identified, allowing for timely intervention and preserving oral health.

Professional Treatment Options for Tooth Cavities

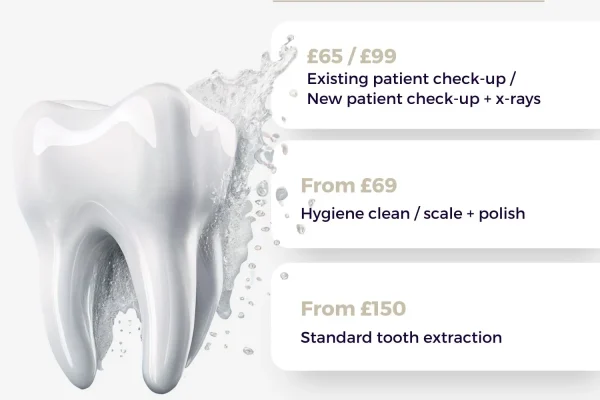

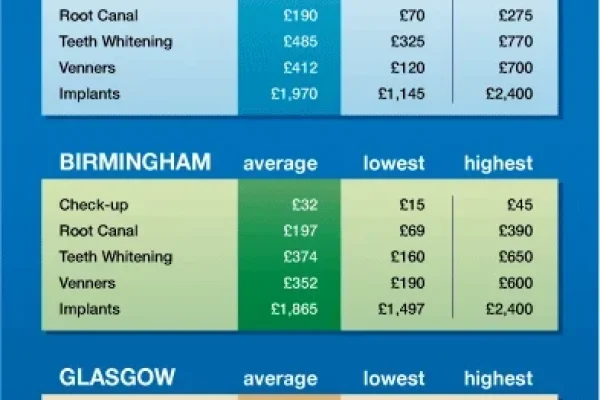

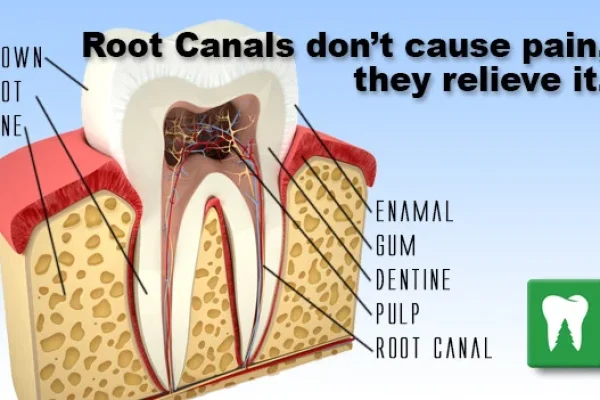

Once a cavity is diagnosed, especially if it’s past the very early, reversible white spot stage, professional dental treatment is necessary. The goal is always to stop the decay process, remove the damaged tooth structure, and restore the tooth’s form, function, and integrity to prevent further problems. The type of treatment recommended depends primarily on the size, location, and depth of the cavity – essentially, how much tooth structure has been affected and whether the pulp (nerve) is involved. For the most common cavities, particularly those that are relatively small to moderate in size and haven’t reached the pulp, the treatment is a **tooth filling**. This procedure involves the dentist numbing the area around the tooth with a local anesthetic to ensure you don’t feel pain. Then, they use dental drills and instruments to carefully remove all the decayed and softened tooth material. The cleaned-out space is then prepared and filled with a restorative material. As discussed earlier, common filling materials include composite resin (tooth-colored and popular for its aesthetics), amalgam (a durable silver alloy, often used for back teeth), gold, or porcelain. The chosen material is placed into the prepared cavity, shaped, and then hardened (often with a special light for composite fillings). The filling seals the space, preventing bacteria from re-entering and further damaging the tooth, and restores the tooth’s original shape and function. Learn more about Tooth Filling. For larger cavities, where the decay has removed a significant amount of tooth structure, leaving the remaining tooth weakened and susceptible to fracture, a **dental crown** might be necessary after the decay is removed. Read about Dental Crown. A crown is a custom-made cap that covers the entire visible portion of the tooth above the gum line, providing strength and protection. This is often the case after a root canal procedure as well, as teeth requiring root canals are typically brittle. If the decay has progressed deep enough to reach the pulp, causing irreversible inflammation or infection (pulpitis), the treatment is a **root canal**. Discover Root Canal Therapy. This involves removing the infected pulp tissue from the pulp chamber and root canals, thoroughly cleaning and disinfecting the internal space, and then filling and sealing the canals. This saves the tooth structure itself but removes the living tissue within. After a root canal, the tooth usually requires a filling or a crown to restore it. In situations where the tooth is too severely damaged by decay, fracture, or infection to be saved with a filling, crown, or root canal, **tooth extraction** (removal) becomes the only option. Following extraction, options for replacing the missing tooth might include a dental implant Dental Implant, a bridge Dental Bridge, or a partial denture Dentures to restore function and prevent surrounding teeth from shifting. The dentist will evaluate your specific situation and discuss the most appropriate treatment plan to address the cavity and preserve your oral health, aiming for the least invasive effective option.

How Do Dentists Treat Cavities?

When you visit a dentist with a cavity, their primary goal is to remove the decay and restore the tooth’s structure and health. The specific method they use depends entirely on how advanced the cavity is. For **small cavities** confined to the enamel or just beginning in the dentin, the most common treatment is a **filling**. First, the dentist will likely numb the area with a local anesthetic injection to ensure you are comfortable and pain-free during the procedure. Then, they will use a high-speed dental drill and other hand instruments to carefully and precisely remove all the decayed tooth material. It’s crucial that all the softened, infected tissue is removed to stop the progression of the decay. Once the cavity is clean and the healthy tooth structure is prepared, the space is filled with a restorative material. The choice of material – composite resin (tooth-colored), amalgam (silver), gold, or porcelain – depends on factors like the location of the cavity, the amount of chewing force the tooth receives, aesthetic considerations, and cost. The filling material is placed in the prepared space, shaped to match the tooth’s contour, and hardened. This filling seals the tooth, protecting it from bacteria and restoring its function. For **larger cavities** where a significant portion of the tooth structure has been lost, a simple filling might not be strong enough to support the remaining tooth. In these cases, the dentist might recommend an **onlay or a crown**. Onlays and crowns are custom-made in a dental laboratory (or sometimes in-office with CAD/CAM technology) and cemented onto the tooth after the decay is removed. A crown covers the entire visible part of the tooth and is used when the tooth is extensively weakened, such as after a root canal. If the decay is very deep and has reached the **pulp**, causing inflammation or infection (pulpitis), a **root canal procedure** is necessary. The dentist (or an endodontist, a specialist in root canals) removes the infected pulp tissue, cleans and disinfects the inner chambers of the tooth, and seals them. This saves the tooth but removes the nerve. A tooth that has had a root canal often requires a crown for protection because it can become brittle. In the unfortunate case where the tooth is **too severely damaged** by decay to be restored by any of the above methods, **extraction** (removing the tooth) is the final option. The dentist will discuss all options and the potential prognosis for the tooth with you before proceeding with any treatment. The dentist’s expertise is crucial in selecting the appropriate treatment to ensure the best possible outcome for the affected tooth and overall oral health.

Understanding Tooth Fillings